Reeling Backward: 12 Monkeys (1995)

The great Terry Gilliam's dystopic (of course!) vision of a future where we can't tell what's real or not seems disturbingly prescient.

The great Terry Gilliam, one of my favorite directors, does not seem like the sort of filmmaker who plans out anything ambitiously enough to be accused of making an unofficial trilogy. Especially since so many of his projects have fallen through, been slashed to pieces by the studio or hampered by disasters, natural or otherwise.

The man has suffered from the worst of luck, countered by being blessed with the finest of imaginations.

However, some insist that “12 Monkeys,” made in 1995 and one of Gilliam’s biggest commercial successes, forms the middle leg of an “Orwellian triptych” that began with his 1985 masterpiece “Brazil” and ended with 2013’s “The Zero Theorem.” Gilliam himself has been rather coy on the topic, alternately denying or seeming to support the idea.

Personally, I think the mad imp just enjoys the attention. Though, if I were to argue for an intentional trilogy, I’d probably include “The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus” as the last entry, Heath Ledger’s final credited role.

I think the best explanation is that the same themes and settings reliably recur throughout Gilliam’s oeuvre, with a focus on tyrannical societies in which people are controlled in mind and body, often made to wonder if the reality they are experiencing is constructed or not. He loves grotesquerie and physical deformity, and his movies often seem to wander into dilapidated cityscapes where the homeless, the paranoid and the crazed intertwine.

You could probably insert “The Fisher King,” another film I adore, into this grouping as well.

“Monkeys” is notable for being one of the few films Gilliam directed that he had no role in formulating the story or screenplay, being hired on after David and Janet Peoples were commissioned with writing a screenplay based on Chris Marker’s 1962 short film, “La Jetée.”

Its twisting tale of time travel, humanity nearly wiped out by a mysterious virus and social/political extremism seems very relevant to this day.

Gilliam didn’t want either Bruce Willis or Brad Pitt as his stars — preferring Nick Nolte and Jeff Bridges — though he ended up being very fortunate in catching them at peak appeal. Willis had just made his comeback in “Pulp Fiction” after a series of bombs. Pitt, after turning heads in “Thelma and Louise,” was cast mostly because he was still small potatoes who came cheap. But then “Interview with the Vampire,” “Legends of the Fall” and “Se7en” were released in the interim, elevating him to the A-list that he has never really left.

Revered and dismissed because of his looks — I still recall a smitten film journalist describing him as resembling “a small sun” — Pitt changed a lot of minds with his turn as Jeffrey Goines, a mentally disturbed inmate at a psychiatric hospital who later becomes an eco-terrorist.

Hyper, bullying and scheming, with strange spastic hand gestures to punctuate his demented speech, Jeffrey is exactly the opposite of the sort of role an agent recommends for their budding star, and it garnered Pitt his first Oscar nomination. It would be 13 years until his next, and 25 until he finally won one.

(For acting, to clarify: a lot of people don’t know Pitt won an Academy Award as a producer of “12 Years A Slave.”)

Pitt is the polar opposite of glamorous, wearing a filthy mental patient gown and later a ridiculous long blonde wig, and one wayward eye appears to be not so much crossed as punctured. It wasn’t much commented upon at the time, appearing to be just a trick of the camera, but I’ve read that Pitt wore a hand-painted contact lens to provide the unnerving look, which makes it seem as if Jeffrey is staring right through us.

It’s a very non-traditional and edgy role for Willis as well, and I don’t think his performance gets all the praise it warrants. He plays James Cole, an inmate (for an unnamed crime) from the year 2035, when what’s left of humanity lives underground, ruled by a cadre of scientists who are still trying to find the cure to the animal-born disease that wiped out five billion people in late 1996.

James is supposed to be sent back to earlier in 1996 to discover the source of the virus so they can formulate a cure to save the remaining humans. But he accidentally arrives in 1990 instead, and his ravings about the Army of the 12 Monkeys, the terrorist group responsible for unleashing the virus, result in him being thrown into a Baltimore psychiatric hospital.

With his shaved head and inmate tattoos on his neck and pate, Willis seems like a pitiful, harmless kook who is usually seen bleeding or drooling, suffering from the latest beating or infusion of psychotropic drugs that James constantly endures. Hunched over and timid, he speaks in a high, simple-minded, childlike tone but is capable of sudden fits of maniacal violence.

One of the film’s foibles is why the scientists select a semi-lucid prisoner like James, who’s dimwitted but has a good memory, as their time-traveling agent, rather than one of their own number. My guess is they see themselves as too valuable, or they’re just afraid their science-y know-how isn’t as reliable as they like to think. At one point James is accidentally sent to the middle of World War I, where he encounters another prisoner/agent, as the scientists hedge their bets with multiple travelers to back up and check up on each other.

(They do seem to eventually wise up, as a scene near the end aboard a plane suggests.)

So James winds up traveling back and forth between 1990, 1996 and 2035, with his own sense of sanity on an equally wild journey. His psychiatrist, Kathryn Railly (Madeleine Stowe), is so good at convincing him he’s deluded that during his final stay in his own time, he comes to believe they’re the figment and the 12 Monkeys plot is his hallucination. By then, though, Kathryn has fallen in love with James and taken up the mantle of his quest in his place, and has to persuade him to come along.

James’ recurring dream that plays several times during the movie is a shootout at an airport. We see a few more details each time, so at alternate times we think the long-haired man being gunned down is Jeffrey, and the blonde woman trying to stop him is Kathryn. We eventually learn, of course, that the man who dies is James himself, and that this is not a dream but a memory, as his younger self was at the airport in 1996 and unknowingly witnessed his own death.

The real culprit was not Jeffrey and his army of animal lovers, but a creepy scientist played by David Morse, whom James was trying to stop from transporting his vials of death across the globe. In a final cathartic moment, Kathryn looks up from James’ dead body and scans around for the boy version of James, giving him a wan smile meant to reassure but that will surely haunt him the rest of his days.

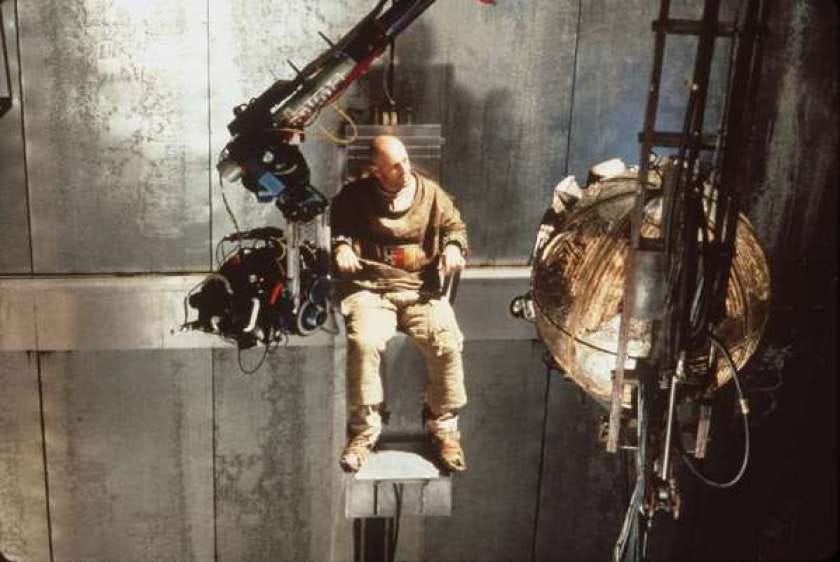

I don’t think I’d seen “12 Monkeys” since it came out a quarter-century ago, though I was surprised at how much of it I had retained. I was struck again by Gilliam’s continual use of a fish-eye camera lens, especially in the 2035 scenes, to convey James’ sense of distortion about what he’s experiencing. It gives the film a vaguely claustrophobic feel, as if we are prisoners in a fever dream.

The strange device the scientists use to interrogate James adds to this feeling, as he is jacked up in a chair high above the ground and robotic arm with various screens and cameras shoved in his face. A love/hate fascination with technology is another hallmark of Gilliam, as we come to rely on machines that interpose themselves between our senses and the real world.

(An architect successfully sued the filmmakers for appropriating his design.)

Seen now, “12 Monkeys” seems both visionary and reactionary. Coming at the dawn of the digital age, it hints at a world where information is everywhere, but we don’t know what is authentic and not. Is most of James Cole’s strange journey imagined or fabricated, as with the infamous ending of “Brazil?” Or does the future really hold that much terror?

Somehow, with Terry Gilliam, all possibilities are equal… and awful.