127 Hours

As the lights came up over the end credits of "127 Hours," I looked at the hand with which I'd been taking notes and asked myself, "Could you do it?"

Before this extraordinary film from Danny Boyle ("Slumdog Millionaire"), I would have said the answer to that question was "no." But then, I also was dismissive of Aron Ralston, the real-life adventurer who hacked off his right arm with a dull knife after being pinned by a rock in a slot canyon for five days in 2003. The sort of people who risk their lives for (in my mind) no good reason, and often lose them in the process are selfish and undeserving of my sympathy, I felt.

What's amazing about the most transformative movie-going experience of 2010 is that, in the end, Aron feels the same way. Not about climbing mountains and canyoneering -- which the real Aron still does fervently, with a prosthetic arm -- but about the connection with other people he had previously eschewed.

Ultimately, "127 Hours" is not about a man who cuts off his own arm, but one who discovers a reason for living that is far more important to him than a mere limb.

"This rock has been waiting for me my whole life," he realizes.

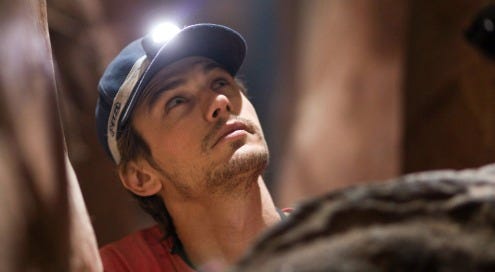

There's a scene near the end where Aron, splendidly played by James Franco, has a vision of his future that could be. (I won't reveal what it is, other than to say it brought tears to these eyes, which do not shed them easily.) The desire to grasp that future is what gives him the resolve to snap the bones of his forearm and saw through his own skin, muscle, nerves and tendons with a cheap multi-tool.

That's the biggest surprise about this film, indisputably one of the best of the year: You think you're going into "127 Hours" for the story of one extraordinary man, and come to realize its message about the indomitable spirit of humanity inside each of us is universal -- as Boyle underlines in his opening and closing montages of bustling crowds from around the globe.

The setting stays largely in a tiny split in the ground in Utah's Blue John Canyon. Aron, an adrenalin junkie who quit his job as an engineer for Intel to climb rocks, is scrambling along alone when a boulder dislodges and pins his hand against the canyon wall.

But Boyle -- who wrote the screenplay with Simon Beaufoy based on Ralston's book, "Between a Rock and a Hard Place" -- continually sends his camera spiraling out of that dark place as Aron's imagination and longing soar. At first his mind turns to mundane but critical things, like the bottle of Gatorade glistening with condensation waiting for him back in his truck parked miles away. But inevitably he ponders the family he's kept at arm's length, and the girl (Clémence Poésy) he pushed away.

Franco's vanity-free performance lets free all his character's selfishness and self-obsession for display. He so clung to his self-image as a hardcore adventurer, photographing and videoing his every triumph and tumble, that he never even bothered to tell anyone where he was going. By the time he's declared missing, Aron calculates, he'll already be dead.

Yes, the scenes of the actual amputation are depicted with graphic honesty, and are hard to watch. But this not some cheap movie that fetishizes gore, but in fact one of the most life-affirming films you'll ever see.

At the end of "127 Hours," not only did I see that Aron Ralston needed to cut off his arm, I believe that I -- or anyone -- could have done it, too.

5 Yaps