Billy Budd (1962)

"You in your goodness are as inhuman as Claggart was in his evil."

So says the master of the ship in "Billy Budd," the 1962 adaptation of the Herman Melville novel directed, produced, co-written and starring Peter Ustinov as the conflicted captain who utters that line. This gripping and overlooked drama presents two men as paragons of innocence and depravity, and uses them as a lens to peer at the reactions they inspire in the muddled masses of the rest of the crew. It's a morality tale writ in stark shades of gray.

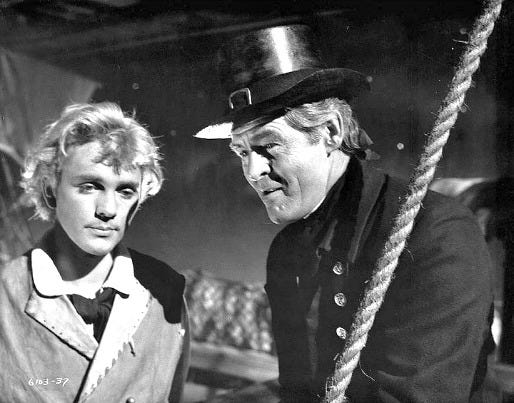

"Billy Budd" was the first major film role for 24-year-old Terence Stamp. Despite playing the title role and the protagonist, Stamp was only nominated for a Best Supporting Actor award at the Oscars. It's obviously a leading role, but older established actors like Robert Ryan and Ustinov received first and second billing, respectively.

It's a full-blooded performance that's built on vacancy. In the commentary track accompanying the DVD, Stamp confesses that he was barely able to speak a word to Ustinov at their initial meeting, so impressed was he by the older man's "powerful aura." It turns out this was the exact quality Ustinov had been seeking, interviewing dozens of young British actors to find someone capable of profound passivity.

He wanted Billy to be a reactive figure who absorbed the worst in other men and returned it with a smile. Indeed, after condemning Billy to death by hanging, Captain Vere (Ustinov) literally begs Billy to despise him for choosing duty over morality. Billy, who gives his age as "17, or 19 ... or 18," responds with his usual quizzical puzzlement. "I did my duty, and you're just doing yours," he says. Vere is more tortured by Billy's absolution than any hatred he hoped to inspire.

When impressed into service in the British navy in 1797, Billy finds the crew aboard the H.M.S. Avenger to be quaking in fear of the cruel master of arms, John Claggart (Ryan). A vicious man who delights in having men flogged for the most minute of infractions -- and even manufacturing ones when they can't be found -- Claggart sees the entire world as an endless chase of prey and hunted. The surface of the sea is calm, he tells Billy, but beneath it every creature is a killer. It's the same on land or on board the ship, he insists.

There's some suggestion that Claggart, who is educated and worldly, once held a high position in the British kingdom and has now fallen low due to outstanding debts or some other scrape with authority. This is a man who does not limit his a vengeful eye to a single person, but casts it upon the whole of society. "I am what I am and what the world has made me," he declares.

Billy, who is guileless to the point of the appearance of idiocy, looks upon Claggart and only sees a man who is lonely and afraid. Claggart nearly succumbs to Billy's offer of friendship, the bile in his soul finally rising to drown any hint of human kindness, which he views as weakness.

It's a chilling performance by Ryan, who often played well-meaning loners. The way he pounds his baton against his leg with every stroke of the floggger's whip, his lips quavering with hunger as he counts the strokes, is one of the most revolting depictions of sadism I've ever seen on film.

Billy, as written by Melville and faithfully translated by Ustinov and co-screenwriter DeWitt Bodeen, is like an angel of God put on Earth unawares of his celestial grace. As a babe he was left on the door of a house in a silk-lined basket, hinting that he was the bastard child of a noble parent. With his nimbus of wavy blond locks, placid blue eyes and slightly androgynous beauty, Stamp truly seems like something not of this world.

Much of this is due to that aforementioned silence. Billy spends an astonishing amount of screen time just staring at and reacting to other actors. When he does speak, he does so in mellifluous tones that impart an organic sort of wisdom, like a child objecting to the wretched constructs of the adult world. "It's wrong to flog a man. It's against his being a man," he says on his first day aboard the Avenger.

Billy also suffers from unintentional silences. When sorely vexed, he is overcome by a stammer that prevents him from any speech. This is pivotal in the final confrontation with Claggart, in which the master-at-arms manufactures accusations of mutiny against Billy, who finally pummels him with a single blow to the chest. After he falls and cracks his head open on a post, the final contemptuous smile Claggart casts at Billy is the devil's sneer of victory.

"Claggart killed you the moment you killed him," Captain Vere tells Billy with sadness.

The officers overseeing the court martial are determined to set Billy free, seeing it as the just triumph of good over evil. But Vere insists their duty is to the laws of the wartime military, not their own personal sense of justice, and browbeats his underlings into returning a death sentence. The idea of stringing up Billy for killing the hated Claggart sets off a mutiny amongst the crew, but Billy quells it with his final, smiling words: "God save Captain Vere!!"

The cast of "Billy Budd" is spectacular. Melvyn Douglas plays The Dansker, an old Danish (he says) sailmaker who seems to have a religious background and acts as the conscience of the ship. The chief officers are ably played by Paul Rogers, John Nevill and David McCallum. Ronald Lewis has a memorable turn as Jenkins, the outspoken chief of the rigging crew who ends up a martyr to Claggart's cruelty. Lee Montague plays Squeak, Claggart's right-hand toady. And John Meillon plays Kincaid, who has his back laid open for insulting Claggart.

"Billy Budd" is a tremendous film, and seen in retrospect its single Academy Award nomination feels like a terrible oversight.

4.5 Yaps