Book review: Making 'A Bridge Too Far'

The 1977 epic war film is underappreciated in the U.S., perhaps because it depicts one of the great military disasters of WWII. Its production gets a superlative history in Simon Lewis' new book.

“A Bridge Too Far” was one of the last great World War II film epics, at least until the genre briefly became popular again with 1999’s “Saving Private Ryan” and “The Thin Red Line,” plus sporadic television miniseries like “Band of Brothers.” It’s extremely popular virtually everywhere in the Western world except for the U.S., where the 1977 film underperformed.

Perhaps that’s owing to the fact it depicts one of the Allies’ greatest disasters of the war, an overly ambitious plan to snatch a bunch of bridges leading through Holland into Germany in late 1944, and thus bring the war to a close by Christmas. Although it succeeded in capturing all the bridges except the last one, it’s still viewed as an example of military foolishness, the largest air drop in history organized in a mere seven days.

The film was equally audacious. Personally financed by mogul Joseph E. Levine, who made his bones on cheapie international flicks redubbed for American audiences, it brought together 14 of the most famous movie stars of the day, including Robert Redford, Laurence Olivier, Gene Hackman, Ryan O’Neal, Liv Ullman, Michael Caine, James Caan, Sean Connery and Anthony Hopkins.

The making of the film has been well chronicled before, with Levine publishing a book on the making of it, and screenwriter William Goldman devoting his own tome in addition to an entire chapter of his seminal book, “Adventures in the Screenwriting Trade.”

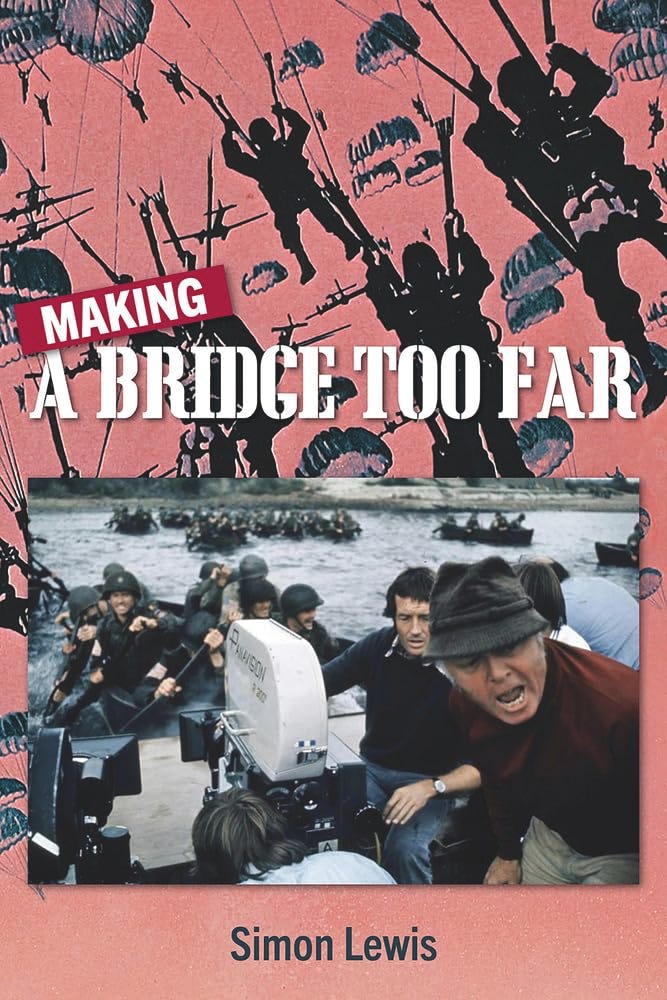

Despite this being well-traveled ground, fans of the movie or just the way movies used to be made before the days of computer-generated effects will surely want to check out Making ‘A Bridge Too Far’ by critic/historian Simon Lewis, which is now available in all the usual places you buy books.

What sets Lewis’ account apart from all others is an absolutely exhaustive amount of interviews with the principles involved, from the director and screenwriter to the assistant directors, cast and small army of extras who played the soldiers throughout the impressive background of the film.

In some cases these interviews took place many years ago, only to be published now, so the book has the feeling of secret long-lost treasure being opened. Many of the important figures, including Goldman, Levine and director Richard Attenborough, have since passed on but their recollections, opinions and impressions are gathered here.

In addition, as a boy Lewis had the incredible fortune of spending a great deal of time on the set to pass along his own eyewitness account.

Attenborough, despite a storied acting career, had only made very small films prior — certainly nothing on this scale with a cast and crew of hundreds, not to mention entire fleets of military planes, vehicles and equipment.

I very much appreciate the portrait the book paints of Cornelius Ryan, who wrote the historical book upon which the movie was based. He was at the front of what was then called New Journalism, where writers plunged themselves into the fray of what they were recounting.

Ryan also was partly responsible for another major war epic, “The Longest Day,” and his long friendship with producer Levine produced not only the impetus to one day turn “A Bridge Too Far” into a movie, but a virtual promise the then 70-year-old Levine had made to Ryan before he died in 1974.

Another amazing tidbit: Audrey Hepburn, who had by then more or less retired from movies by choice, actually grew up in the town of Arnhem, where some of the worst fighting took place for the military venture than became known as Operation Market Garden. She was considered for the role Liv Ullmann ultimately played, a local woman who helped many of the Allied wounded, but Hepburn’s tragic memories of the battle proved too much for her.

Writer Goldman, in an unusual role for a script man, Goldman was on the set for virtually the whole shoot. Despite turning in a masterstroke of narrative structure winding together dozens of principle characters and complicated overlapping events, Goldman found himself continually attacked by the military advisors of the film, many of them veterans of Market Garden, for switching around some historical facts to make things more dramatic.

A primary example: Redford, arguably the biggest star in the world at the time after the success of “The Sting,” found his role as Major Cook, who led the daring crossing of the Waal River at Nijmegen, plumped to the point he was leading the attack in scenes where his character wasn’t even present.

Although the book takes pains to show how the big-name actors generally accorded themselves well on the incredibly complex production, Redford is depicted as a bit of a headcase, arguing with the assistant directors and showing up late for a critical shoot when the production had negotiated control of the actual bridge where they were shooting for just one hour.

More fascinating tidbits:

Some of the production designers for the Arnehm battle also worked on the city battle scenes for “Saving Private Ryan.”

Attenborough is depicted as a model of grace and encouragement, calling everyone on the set “darling” — mostly because he had trouble remembering everyone’s names. He only took the job as a package deal for Levine to finance his decades-long passion project, “Gandhi,” which they made a few years later.

Olivier was in quite poor health, and could barely pull the cart scene in the very last shot of the film.

Dirk Bogarde was very unhappy with his part playing Lt. Gen. Browning, one of the main planners of the operation who comes across as the heavy of the piece because of his seeming indifference to the lives of the men he put in danger. Even more fascinating: Bogarde actually served under the real Browning during the war.

Hackman was bewildered playing against the then-unknown thespian Denholm Elliott, feeling the Brit acted circles around him.

A great bulk of the book is dedicated to Attenborough’s Private Army, or APA, the sprawling crew of extras, stunt men and bit actors who played the soldiers — in some cases swapping sides from German to British to American for different scenes. They were a hard-partying crew who spent much of their pay getting sloshed every night at the local Dutch taverns, and seeking favors of the local ladies.

(It’s lively stuff, but for my taste needed to be pared back as it at times over-dominates the book’s main thread.)

If you’ve not seen “A Bridge Too Far,” I enjoin you to watch as it’s not only a terrific war picture, but also one that isn’t afraid to show the often capricious way battle is conducted, with the commonfolk always the ultimate victims. It’s a tale of grand bravery but also astounding hubris.

And if you’re sufficiently intrigued, check out Simon Lewis’ book for the most complete possible version of the story behind the story.

Love this! Never entirely convinced by Dirk's casting as Boy Browning. And at the time it caused no end of a stink. Letters to The Times. Daphne du Maurier and the rest...