Carbon Copy (1981)

I remember "Carbon Copy" as one of the first "grownup" movies I was allowed to see in the theaters. It's a film that's more notable for its place in cinematic history than the actual merits of the flick itself, though those are not inconsiderable.

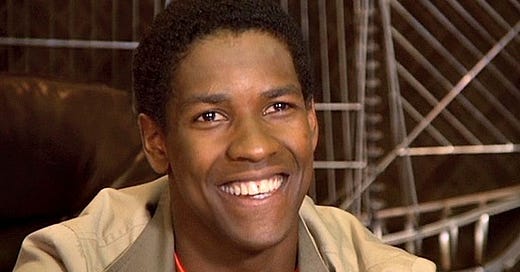

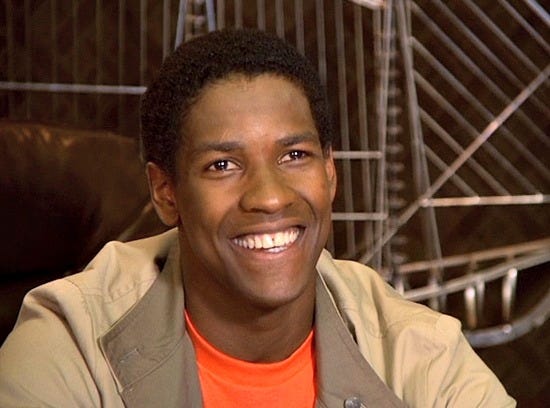

Topping the list is the film debut of Denzel Washington. If you were to draw up a list of the greatest film actors of the past 30 years, here would be mine (in no order): Meryl Streep, Morgan Freeman, Tom Hanks, Anthony Hopkins, Denzel Washington. Oh, and Jeff Bridges ... he's quieter than the rest, but no less deserving.

Washington gets the " ... and introducing" treatment here at the end of the opening cast credits. It's not exactly an auspicious debut for someone of his stature, and the film has largely been forgotten today.

Mostly that's owing to its racial themes, which were mildly progressive for 1981 but seem hopelessly antiquated — even a little insensitive — for today. Not to mention that almost instantly obsolete title, a reference to an early form of document reproduction that I would guess few under age 40 even recognize.

Screenwriter Stanley Shapiro had a busy career for three decades, a comedic master who was nominated for the Oscar four times, winning once for 1960's "Pillow Talk." This was back in the day when the Academy wasn't shy about recognizing funny movies, unlike today. (Unless it's comedy of the pitch-black variety, a la "About Schmidt" or "The Descendants.")

Shapiro's last feature film credit was the wonderful "Dirty Rotten Scoundrels" in 1988. His screwball comedy roots and rapid-patter style of dialogue are evident in "Carbon Copy," a movie that always seems like it's in too much of a hurry. Scenes race to their conclusion like the spirit of Louis B. Mayer was sitting behind director Michael Schultz with a stopwatch.

Speaking of Schultz, he was a notable African-American director working in mainstream Hollywood for decades, with credits like "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band," "Car Wash" and a number of Richard Pryor comedies. Approaching age 80, he's still active in television today working on popular series like "Arrow" and "Black-ish."

Washington's character starts at the forefront of the story, and gradually gets pushed aside. "Carbon Copy" is really a star vehicle for George Segal, who plays Walter Whitney, a harried 41-year-old Los Angeles corporate executive squeezed from all sides by his shrew wife, Vivian (Susan Saint James), and his boss, Nelson (Jack Warden), who's also his father-in-law.

Then 17-year-old Roger Porter (Washington) shows up on his doorstep, claiming to be his son from a long-ago romance with an African-American woman. The setup is that Walter truly loved Roger's mother, but sold out to marry into money and the big time. Nelson insisted that Walter cover up the romance so as not to upset the WASP elite of San Marino, a tony suburb of L.A., as well as change his surname from Weisenthal to Whitney, for similar reasons.

Walter's not a bad guy, but he's reaping the whirlwind of bad life choices all coming back to haunt him at once.

The movie opens on an ... uncomfortable note. Walter awakens Vivian with demands for sex, the result of long pent-up frustration, which grow increasingly strident, only to be dispelled when the maid walks in on them with a silver breakfast platter. Vivian even whips out the "r" word, and she quickly reports the whole episode to daddy, resulting in a talking-to from the old man.

Nelson is a real piece of work. He's an old-school sort who believes it's the duty of the rich and powerful to stay that way. But he's got his charms.

On the one hand, he wields the carrot of reminding Walter that he can become The Man one day if he follows the straight-and-narrow path, while also threatening the stick of blackmailing him about his black bastard son and Jewish heritage.

Nelson genuinely wants Walter to follow in his footsteps, even if he has to hammer his feet to a pulp to make the shoes fit. "Learn to trust unhappiness, Walter," he counsels.

Washington is a revelation from the moment we first lay eyes on him. Just 23 when the movie was shot, he's a lithe and charismatic presence from the get-go. He adopts the demeanor of a streetwise tough, waltzing into Walter's office and admiring all the trappings: big oak desk (soon adorned by Roger's feet), three-piece suits, expense account lunches, Rolls Royce company car, etc. He makes out like he's looking for a payday.

In the end, it's revealed that Roger is actually a smart, hard-working kid who graduated from high school early and is already in his second year of pre-med at college. He just wanted to meet his old man, take his measure and see what happens next. Part of him would take great delight in seeing his world unravel — which is exactly what happens. But he finds himself burdened with a growing fondness for Walter.

Questions of parentage are quickly set aside for storytelling convenience — despite the only ostensible proof of progeny being some old letters of his mother's Roger found after her death. (Speaking of which: For someone who just lost his mom, Roger doesn't seem very broken up about it.)

The movie doesn't take time to really explore how a middle-aged guy like Walter feels about having a black son, moving right into screwball comedy territory. First he introduces Roger to Vivian as their summer guest as part of a program for underprivileged kids, after convincing her that all the other rich wives of San Marino will want "one" — and she'll be the first.

Mere minutes into this new arrangement, however, Walter corners his wife with a hypothetical about accepting Roger if he were his "natural" son, just as he has (grudgingly) accepted and adopted her daughter from a previous marriage, a spoiled brat of the first order. When she takes the bait and Walter reveals that Roger really is his son, everything falls apart quickly.

He's thrown out of the house, loses his job, has his Rolls impounded and all his credit cards cut up, his assets frozen, etc. His oldest friend and attorney (Dick Martin) even drops him as a client to represent Vivian in the divorce. The lawyer he refers him to — of course a black guy, played by Paul Winfield — tells Walter all he's got in the world is whatever he has in his wallet, some $62.

He explains to Walter that he's being forcibly put through "social menopause:" "You're going through a change of color, Mr. Whitney. You don't want to play the game as a white man, so they're going to let you watch it as a black man."

That's of course going too far. Being a penniless, socially outcast white man in 1981 was still preferable to most iterations of black life of that era. Read a certain way, the film is a cautionary tale during the early days of Reagan.

Anyway, Walter and Roger suffer the life of paupers — for a few days. He can't get a job after being blacklisted, so he takes to day labor cleaning out horse stalls (still wearing his three-piece to the gig). This leads him to reflect upon his new life of shit, and the resolve it brings. "I'll shovel it. I'll live in it. But I won't take it."

Meanwhile, Roger pawns his golf clubs and other stuff for cash to get them by another day. He also reveals that he has a car of his own that he bought for "$14 and a toaster," which is a comically battered 1959 or '60 Chevrolet Bel Air, the front end mangled and one tire wobbling like a dancing hippo.

"Carbon Copy" takes the issue of divisions between black and white and between rich and poor and turns it into a prank, a springboard for laughs rather than social observation. For example, there's a scene where Walter, desperate for cash, challenges an out-of-shape father and son to a game of basketball for five bucks, thinking he's got a ringer because every black kid can play hoops, right? And of course Roger turns out to be completely inept, sailing the ball eight feet over the backboard.

We're never quite certain of how deeply the film is in on its own joke. Is that scene funny because of Walter's presumptions about black athletes, or our own? Are we laughing at the African-American who can't shoot a basketball, or at Walter for assuming that he could?

Thank God, at least the movie doesn't have a dancing scene.

I can't quite bring myself to dislike "Carbon Copy," however. The dialogue is still snappy even if the plot feels like it's hopped up on speed. And the cast is a pure pleasure: the folksy, slightly neurotic charm of Segal, and young Washington feeling his oats on the big screen.

Sometimes great things arrive unheralded.