Class of 1983: "The Outsiders"

In the “Class of …” series, we take a monthly look back at films celebrating either their 20th or 30th anniversary of initial release this year — six from 1993 and six from 1983. The rules: No Oscar nominees and no films among either year’s top-10 grossers.

For a film that builds toward a blood-and-mud battle royale between teenagers, the most interesting grapple in “The Outsiders” exists far from the narrative and inside its director, Francis Ford Coppola.

Here, for the first time, was Coppola cowed. “Apocalypse Now” had infamously consumed three years of his time and shaved as-yet-undetermined years from his life — tremendous ambition by way of frightening insanity. But at least that gamble was rewarded with eight Oscar nominations, box-office glory and deserved cinematic immortality.

“One from the Heart,” a self-financed musical intended as an “antidote” to “Apocalypse’s” grueling grind, received no such hosannas. Coppola likely wishes the general regard of “Heart” as his first misfire after a 10-year hot streak was as bad as it got. He lost 97 percent of his investment — plummeting so deep into bankruptcy that many of his films over the next 15 years were made primarily to pay debt.

Coppola’s subsequent movies were a mixed bag of period-piece dynamos (“Peggy Sue Got Married,” “Tucker: The Man and His Dream”), openly commercial efforts (“The Godfather Part III,” “Bram Stoker’s Dracula”) and outright duds (“Jack,” featuring Robin Williams as a 10-year-old with a genetic condition that makes him look 40).

But “The Outsiders” was the first of this lot, an adaptation of S.E. Hinton’s acclaimed novel about teen angst written when Hinton was herself a teenager. Lean and muscular, it’s a tale of 1960s social conflict among Greasers, a gang whose income is as low as their self-esteem, and the upper-crust “Socs” (short for “socials,” pronounced “Soshez") that spills into tragic violence.

The film is best known today as a petri dish for the stardom of its seven leads, all of whom became ’80s youth icons — C. Thomas Howell, Rob Lowe (making his debut but barely registering), Emilio Estevez, Tom Cruise (then in a career-making year and just months from “Risky Business”), Patrick Swayze, Ralph Macchio (an impossible 21 years old) and Matt Dillon (then the group’s most experienced).

But “The Outsiders” finds Coppola in a bare-knuckle brawl between the source material’s inherent grit and his penchant for grandiosity. It’s not an entirely unexpected response from an auteur who suddenly found himself bound in fealty to banks and executives.

Coppola had no interest in “The Outsiders” until he received a persuasive letter from a California librarian and her students. And the artistic cross-purposes on display are suggested in correspondence from Coppola’s longtime producer, Fred Roos.

Of the students, Roos asked for essays about scenes they liked and disliked, alternate title ideas and whether omitting the climactic gang fight would upset them because it seemed “(the characters) would have learned something during the course of the story.” Taking a tone usually reserved for studio notes and comment cards suggests a drive to make money, not a fully realized statement on the unique mysteries of teenage human nature. The result is a film divided against itself — by turns both evocative of an era and stripped down to its most marketable parts.

Looking back, although nowhere near as gaudy or glitzy, certain moments of “The Outsiders” feel like the rough first draft of a Baz Luhrmann adaptation. Coppola certainly shares that sense of epic, soundstage showmanship and how, when carefully and cautiously filtered through the language of cinema, artifice can heighten emotion without cheapening it — perhaps even elevate it into the realm of mythology.

Here, Coppola is as hit-and-miss as Luhrmann can be, but he also lacks Luhrmann’s luxury of time: Give “Romeo + Juliet,” “Moulin Rouge!” and even “Australia” an hour, and their earnest sincerity works on you (or maybe just wears you down). When given bankable beefcake to display and only 91 minutes to do it, sappy Stevie Wonder songs and push-ins on cherubic faces reciting their own deathbed letters will only ever feel mawkish . (“The Outsiders” is also so threadbare that a bit of voiceover from Lowe seems shoehorned in to remind us he is, in fact, Howell’s character’s brother.)

But Coppola described “The Outsiders” once as “ ‘Gone with the Wind’ for 14-year-old girls,” and if that doesn’t sound like the sort of films Luhrmann has been making for the last 20 years, nothing does. Nowhere is the old-Hollywood aesthetic more prevalent than in this scene between Ponyboy (Howell) and Johnny (Macchio), two Greasers on the lam after Johnny knifes a Soc in self-defense.

Like “West Side Story” before it “The Outsiders” is stuffed with iconographic compositions that hint at redemption. But it’s also countered by deep focus and Dutch angles that suggest an annihilative reckoning, especially when Johnny saves Ponyboy’s life the only way he knows how.

Coppola also thrusts viewers into these teens’ heightened headspace during a handful of climactic, claustrophobic moments with Dillon’s Dallas. He’s the Greaser with a past in New York who gives Ponyboy and Johnny cash, a heater and a hot tip on a train out of town.

Dallas ultimately commits suicide by cop. But in this striking scene just beforehand, he’s forever disabused of any heroic notions. Perhaps it’s Coppola’s attempt at commentary by way of contrast — how the appealing artificiality of the movies, especially to teenagers, can often be sliced in two by life’s harsh realities.

But in the 1983 version, that notion feels as trapped by fate as Dallas and Johnny. Coppola recut the film in 2005 to add 20 minutes, replace his father Carmine’s aggressively sucrose score with period sounds, and restore character and context absent from the original. (Lowe also gets screen time befitting a character whose brotherly bond was only hinted at in 1983.)

This probably sounds like a windup to a shopworn argument: Studio meddling ruined a film that would have been a classic left in the hands of its master. But while Coppola’s recut version certainly improves many things, it mucks up others. While anachronistic Americana in Carmine Coppola’s score pushes the original into overpowering sentimentality, his son’s soundtrack switcheroo diminishes Dallas’s death.

ORIGINAL VERSION

RECUT VERSION

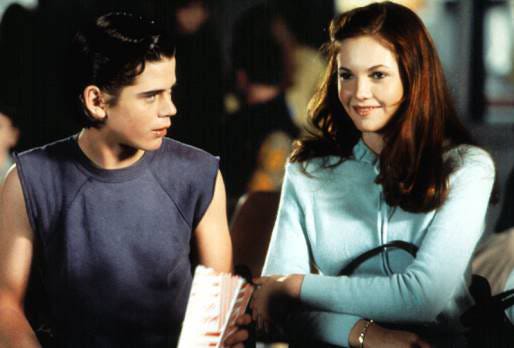

Still, there are moments of unquestionable greatness in either version of “The Outsiders.” Its first act is a haunting short film all on its own — Ponyboy, Johnny and Dallas sneaking into a drive-in and meeting undeniably dishy “Cherry” Valance (Diane Lane), a Soc attracted, even if anthropologically, to these bad boys. What could grow heated, hormonal and lusty instead plays out like a series of truthful confessions, swallowed up by the relentless Oklahoma wind.

And although Ralph Macchio’s bankability ended with the decade, his work here is outstanding — even when combating Coppola’s corniest tendencies. Johnny is a good kid pushed into an impossible situation, someone who only learns to appreciate the life ahead of him at the least opportune time. Yes, Johnny’s admonition to Ponyboy to “stay gold” is the film’s oft-quoted (or derided) emotional highpoint, but Macchio is flawless in Johnny’s tender expressions of friendship and tearful moments of weakness.

Ultimately, “The Outsiders” feels like two movies awkwardly thrown together — one a tough-acting antiseptic to the sanitized-suburbia Spielberg fantasies that ruled the era’s box office, the other a besotted valentine to widescreen epics of old.

Perhaps what Coppola identified with most at the time — more than teen angst and thanks to the misfortunes from which, artistically speaking, he never fully recovered, was the Robert Frost poem quoted in the film: “So dawn goes down to day. Nothing gold can stay.”