Class of 1984: "Supergirl"

In the “Class of …” series, we take a monthly look back at films celebrating either their 20th or 30th anniversary of initial release this year — six from 1994 and six from 1984. The rules: No Oscar nominees and no films among either year’s top-10 grossers.

Last month, DC and Marvel finally addressed a longstanding, controversial $200 million question: When will their glut of (mostly) excellent superhero films finally focus on a female? For DC, the answer is 2017, and for Marvel, it will be in 2018.

Most people cite DC’s abominable “Catwoman” or Marvel’s feeble “Elektra” as the top reasons for this decade-long drought on either side of the comic-book turf war. (“Tank Girl” and “Barb Wire,” 1990s adaptations from fringe imprints, are footnotes.) However, both arrived before the recent renaissance led at DC by Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy (which “Catwoman” beat by one year) and, at Marvel, by the Avengers’ ascension. With 10 hits in six years, it’s hard to believe Marvel didn’t even fire up its own studio machine until 2008, three years after mourning became “Elektra.”

DC and Marvel simply exert more quality control today, which, depending on where you stand, is either exhilarating or stifling. When you plant six-years-out flags on the release calendar, there’s no room for a rogue mistake regardless of the star’s sex. That’s not to say DC or Marvel's upcoming films won’t bomb or be bad, just that each camp will carefully calculate and finely calibrate every choice. The absence of a female-focused film from either company in the last decade has little to do with a lack of interest. It has everything to do with the exponentially weighty cultural fallout should they foul it up. As everyone involved with “Green Lantern” will attest, there is no commutation on the sentence handed down in 140 characters or less. And in a world where Katniss Everdeen factors into real-life rebellion, neither DC nor Marvel wants to be seen as reductive, backwards rubes who flub the finer points of empowerment in entertainment.

To really understand why today’s Marvel and DC regimes have exercised extreme caution in any solo flights with the fairer sex, you have to go back even farther. You have to think about the early 1980s, when there was really just one superhero on screen, Superman. You also have to, rather regrettably, revisit “Supergirl,” a 1984 spinoff so rancid it hermetically entombed the entire Superman franchise for 20 years.

Father-and-son producers Alexander and Ilya Salkind staked their careers on a Superman film. It took them five years, but 1978’s “Superman” became Warner Brothers’ biggest hit ever and cemented the Salkinds as strong-armed purveyors of splashy spectacle. How far did their iron-fisted insistence reach? They essentially forced “Superman” director Richard Donner off of a mostly finished “Superman II” (filmed simultaneously with the first), replaced him with Richard Lester (whom they let reshoot enough scenes to gain full credit) and all but erased Margot Kidder’s role as Lois Lane in 1983’s “Superman III” after she publicly criticized their tactics.

In negotiating their original deal, the Salkinds also obtained rights to a Supergirl spinoff. After the comparative financial disappointment of “Superman III,” a film about Kal-El’s cousin, Kara Zor-El, seemed a good way to enliven the franchise. Better still, Christopher Reeve intended to appear as Superman and strengthen connective tissue. He also brought them “Jaws 2” director Jeannot Szwarc, whom Reeve fondly recommended after their work together on 1980’s “Somewhere in Time.” In the film, Supergirl was to save a weakened Superman, and Earth, from Selena (Faye Dunaway), a witch into whose evil hands the Omegahedron — an intergalactic power source — had fallen.

No price seemed too high for the Salkinds. Visual effects for "Supergirl's" opening credits are said to have cost $1 million. They were willing to offer Dudley Moore $4 million for a small role as a warlock. (Moore instead suggested longtime collaborator Peter Cook, who almost certainly earned much less.) And the film's end credits include executive assistants, the assistants to those executive assistants, and masseuses. However, no hands could ultimately smooth out "Supergirl's" unexpected creative knots and, ultimately, an irreversible contortion of the Salkinds’ success.

Just weeks before production, Reeve bailed, undermining the planned premise. Rather than retreat and return when ready, as even Marvel or DC would likely do today, the Salkinds and fall-guy screenwriter David Odell performed the most woeful pivot possible. Attributing Superman’s absence from the film to a “peacekeeping mission several-hundred billion light years away,” the script barely bothers to conceal its shiv. In a true eighth-banana stretch, the only returning character is ... Marc McClure’s Jimmy Olson. And “Supergirl’s” retooled plot ultimately boils down to a heroine and a villainess catfighting over a shirtless Schlitz-slugging landscaper.

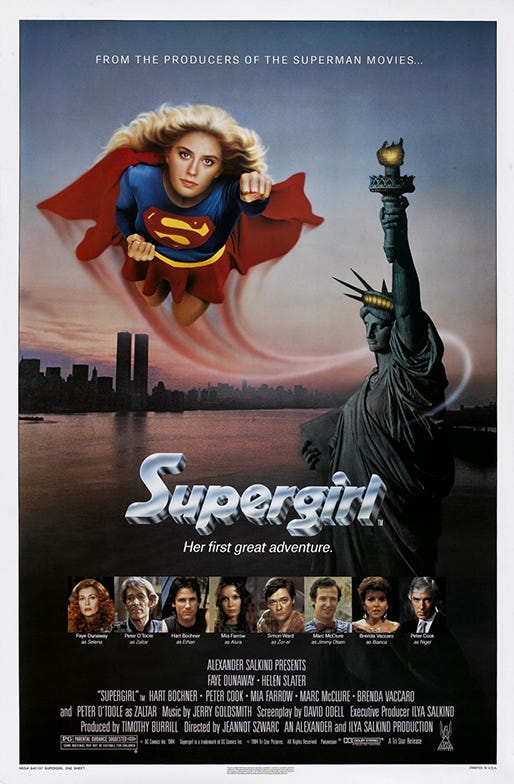

Even the poster is perversely inept — promising a New York story from a film set in Chicago, or Chicagoland, or, you know, those vast mountain ranges for which northern Illinois is known. It befits a movie, though, that just trots out iconic nostalgia it never really earns. Sadly, its four-word tagline — “Her first great adventure” — bats .500.

Only Jerry Goldsmith’s score (wisely minimizing John Williams’ triumphant fanfare for its own ideas) approaches any level of true grandeur. Even then, Goldsmith's occasional button-mashing synthesizer notes seem like wowee-zowee sound effects that lure kids into buying cheap dollar-store toys that will quickly break.

And that cast. It’s as if the Salkinds trolled a “Hollywood Squares” Rolodex for the era’s elder statesmen and familiar faces to wink and wave before walking out of the movie for large swaths of time. Alongside Dunaway and Cook, there’s Mia Farrow as Kara’s mother, Peter O’Toole as wily scientist Zaltar and Brenda Vaccaro as Bianca, Selena’s silly sycophant. Most of them exert the minimum effort expected after a confirmation of deposited funds. Only Dunaway, as the film’s distaff Lex Luthor, breaks off the knob with a genre-appropriate cackle-and-screech hamminess. It helps that Odell, for all of his faults, gives Selena vintage ink-and-print zingers like “I can make the sky rain coconuts with pinpoint accuracy, but I still can’t control men’s minds.”

“Supergirl” ultimately undid the Salkinds, Szwarc and, for at least the next two decades, the franchise. Although the Salkinds financed the film themselves, Warner Brothers retained distribution rights. The studio held a spot in July, but the Salkinds insisted (for whatever reason) on a Thanksgiving release. Perhaps sensing the worst kind of turkey, Warner Brothers relinquished distribution rights, then snatched up by the nascent TriStar Pictures, which undoubtedly thought it had a franchise on its hands. “Supergirl” went on to gross just $14 million — the lowest take of any modern-day Superman(ish) movie, claiming that infamy by $1 million over 1987’s abysmal “Superman IV: The Quest for Peace,” after which there were no Superman films until 2006.

The Salkinds had nothing to do with “Superman IV,” having had to sell their rights to less-sophisticated schlockmeisters Cannon Films after the financial failures of “Supergirl” and 1985’s “Santa Claus: The Movie,” another loudly unsuccessful blockbuster directed by Szwarc. (The director is still working, having since returned to the network TV field from which he started, overseeing episodes of “Heroes,” “Scandal,” “Fringe” and, coincidentally, “Smallville.”)

Not surprisingly, there are about a half-dozen versions of “Supergirl,” ranging from a German version that runs 89 minutes to an unreleased 150-minute cut that seems like a threat. Szwarc’s director’s cut, painfully clocking in at 138 minutes, was exhumed for a DVD release after its discovery at London’s Pinewood Studios in a container prophetically marked “DO NOT USE.” "Supergirl" is unsalvageable at any length, but the 124-minute international cut (which adds back 20 minutes chopped from a nigh-incomprehensible U.S. version) at least fleshes out a few key points.

That version lingers a little bit longer on a prologue in Argo City, an “inner space” enclave where Krypton’s last known survivors have set up shop. The Omegahedron, which resembles a collectible Christmas ornament, is Argo City's life-sustaining source of electricity. Imagine Great Britain opening its power grid to Banksy, and that’s what happens here as Zaltar nabs the Omegahedron for experiments. Through a series of incidents, the Omegahedron shoots into space and heads for Earth, leaving Argo City to die and Zaltar to condemn himself to the Phantom Zone (the prison to which General Zod and his cronies were banished in “Superman II”). O’Toole approaches this life-and-death decision with all the dramatic power of a man whose favorite dish has left the menu and who must order something else.

Hope seems lost until Kara travels through a “binary chute” to follow the Omegahedron, which crash lands in Selena’s custard cup on Earth. If you thought “Interstellar’s” vision of trans-dimensional space seemed absurd, perhaps something that suggests matte shots of cracked eggs mixed with colored dye is more your speed. (Don't even try to argue about effects limitations. You know there were pretty decent effects in 1984.)

Kara arrives on Earth as Supergirl in a skimpier version of her cousin’s super-suit, and it’s here the international cut affords its loveliest bit of breathing room. As Supergirl discovers she can fly, crush rocks and use heat vision, it lets her get her bearings and clues us in without belaboring the point that she’s exactly like her cousin. Also clearer in the longer version: Supergirl suffers from Superman's limitations, thus her inability to detect the Omegahedron's whereabouts after Selena conceals it in lead.

Szwarc wanted Brooke Shields to play Supergirl, but the Salkinds overruled him in choosing a then-unknown Helen Slater. Only years later would Ilya Salkind call it a mistake. Slater is certainly a tabula rasa, and not a particularly good one; she’s a non-starter, but that would only stand out if the movie she were in had any ignition. Besides, she stabilized into a solid, if mid-level, career.

Shields would have been a bigger marquee draw, but perhaps the Salkinds sought to avoid the sexualized controversy of her previous roles. However, that didn’t stop them from framing Supergirl’s first earthling encounter as a lascivious, sexually unsettling scenario. A pair of would-be rapist truckers circle her, leer and flick up her skirt. (Matt Frewer, the future Max Headroom, plays one of the truckers, wearing an A&W T-shirt in some of the most ill-advised product placement ever.)

“Why are you doing this?” Supergirl asks as they fondle her behind. “It’s just the way we are,” goes their troublesome response before she, of course, hands them theirs. Look, “Supergirl” isn't the sort of superhero movie in which the primal questions of whether mankind, in all of its depravity, is really worth saving will be dissected. (Leave that to Christopher Nolan.) But couldn’t the Salkinds simply have had Supergirl save someone from a light mugging or something? As it stands, the scene just introduces thematic discomfort into a movie already hobbled by technical ineptitude.

From there, “Supergirl” settles into a listless, lifeless slog. Just because Supergirl can’t sense the Omegahedron shouldn't mean that she should seem not at all concerned that her people are dying somewhere in another dimension. Never once does the film return to Argo City. How hard would it be to show a few sickly kids and grimly resigned adults? Instead, "her first great adventure" marks time in a tremendously sexist fashion — setting up a supernatural love triangle between Supergirl, Selena and Ethan (Hart Bochner), a frequently shirtless groundskeeper.

Bochner is best known for his eminent douchebaggery as the coke-sniffing, smooth-talking Ellis from “Die Hard.” But here, he’s a Tony Danza-Henry Winkler hybrid who gulps booze with wide-mouthed ferocity and, once poisoned by Selena’s love spell, spews forth Lord Byron sonnets. Most movies would benefit from rendering a guy like Ethan mostly useless as "Supergirl" purports to do — emphasizing the superior female might on either side of the good-bad divide. Sadly, Supergirl merely moons over him like Mary Katherine Gallagher (even practicing her make-out sessions with a mirror), Selena acts as if Ethan’s love is more important than universal power, and the two lock horns for his affection during ill-conceived effects sequences that drag on for an agonizing hour. The worst is an “action scene” in which a renegade tractor wreaks havoc in a small town — a watch-checking snoozer that allegedly took 22 days to film and feels just as long onscreen.

Eventually, Selena banishes Supergirl to the Phantom Zone, where she reunites with Zaltar. It’s mentioned that others in the Phantom Zone, like Zod, are all “over the hill there,” but their trouble-causing appearance — “Supergirl’s” only potential saving grace at this point — never arrives. Zaltar numbs the pain of his bad decisions with “squirts” of some indeterminate booze, but he sobers up long enough to help Supergirl escape through a “singularity” and sacrifices himself in the process.

Selena and Supergirl’s final grapple comes as the former controls a Balrog-esque shadow demon shrouded in effects fog so as not to reveal its sketchy design. Eventually, aided by Zaltar’s great-beyond whispers, Supergirl figures out a way to hurl Selena and Bianca into a storm where the shadow-monster eats them both with a surfeit of scowling and screaming. So content is the movie to end then that the heroine’s day-saving return to Argo City is only inferred.

“Supergirl” is a movie whose very bones have been irreversibly rotted away by catastrophe — an actively sexist insult that obliterates one distinct appeal of a female superhero movie, which is to see a woman leveling the playing field when it comes to derring-do. At least it’s getting a second, likely successful chance (albeit on TV) in 2015 as a CBS series from Greg Berlanti (the mastermind behind the CW's surprisingly nimble “Arrow” and “The Flash”), Geoff Johns (DC Comics’ chief creative officer) and Allison Adler (a former writer for Fox's “Glee” and NBC's “Chuck”).

When it comes to long waits for female superheroes at the movies, wouldn’t we all rather take 10 years of stage-setting to do things right than hastening another massive stinker and forcing another 30-year statute of limitations? Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel will undoubtedly kick down very big doors all in due time. "Supergirl" simply knocks itself out by heedlessly running into one.