Class of 1993: "Carlito's Way"

In the “Class of …” series, we take a monthly look back at films celebrating either their 20th or 30th anniversary of initial release this year — six from 1993 and six from 1983. The rules: No Oscar nominees and no films among either year’s top-10 grossers.

Rare is the good film that offers up its ending wholesale in the opening frames. Screenwriters surely intend it as a bit of brain-frying disorientation right as you’ve settled in. But it often feels like tawdry, vainglorious showmanship — a choice of cheap distraction over clear tonal direction.

It’s a device that tends to suck any surprise right out of a story, with the first and second acts marking time until characters catch up with a moment we know is coming. But the exact opposite is true of “Carlito’s Way,” which (spoiler alert going on drinking age) opens with Al Pacino’s title character taking a pair of point-blank bullets to the stomach on a train platform.

No matter what happens to Carlito Brigante — a Puerto Rican drug dealer freed from a 30-year prison sentence after his conviction is tossed out — we know it will lead to two the hard way. What we see is not a vivid dream, a hazy premonition or an alternate reality, and in the sense of a conventional narrative, it ruins the movie.

But that supposes “Carlito’s Way” has no aspirations beyond a conventional narrative of the gangster film. Admittedly, that seems likely given that it reunites Pacino with director Brian De Palma, who previously teamed 10 years earlier on the gloriously garish remake of “Scarface” (which this column will revisit next month).

Tony Montana was a fascinatingly vulgar, violent antihero whose hubris and bluster only facilitated his gruesome demise. “Carlito’s Way” superbly subverts our expectations of seeing similar bad-boy behavior lead Carlito to the reaper’s doorstep. By opening with his death, the film proclaims that it’s less about what happens to Carlito than what happens within him: an internal transformation from rootlessness to restfulness tracked throughout the film, and which he just might not be around to enjoy for long in the corporeal sense.

Sounds like a glum, violent and tragic downer. And for the disappointed who expected “Scarface 2,” or who bolted for the exits even a few seconds too early, it might have seemed that way, but more on that later.

With such an unabashedly positive, romantic guy at its center, much of “Carlito’s Way” seems strangely upbeat, and even this graphically violent death ultimately feels peaceful. Its composition is immediately heightened and intensely striking. Composer Patrick Doyle’s elegiac music swells as the hurly-burly of a homicide crime scene slows to let us see what’s almost surely Carlito’s consciousness slowly turning upside-down and sideways. It’s just the start of the most emotionally engaged film ever from De Palma, a surgeon’s son with his own clinically efficient oeuvre of ostentatious style, sexually aggressive content and vivid violence.

Landmark French cinema magazine Cahiers du Cinéma named “Carlito’s Way” the best film of the 1990s. While that may be a superlative too far, it is easily the best in De Palma’s compelling, if frequently confounding, career. Although still rolled into a distinctly sleek De Palma package, it’s the rare instance in which optimism and warm, careful character observation trump his penchant for coolly detached cynicism.

As Carlito reflects on the more immediate events in his life, the film places us in a New York courtroom circa 1975. Much to the court’s consternation, Carlito is being freed after five years of a 30-year stint, thanks to illegally overzealous wiretapping.

Carlito’s counsel, David Kleinfeld, has worked doggedly to free him, and the perspiration of his labors pools at the apex of a high-shaved forehead and the unruly-perm hairline on a nearly unrecognizable Sean Penn, who resembles a Sweathog who shuffled his way uptown without anyone noticing.

This comeback role for Penn — then absent from the screen for three years — was mostly a way to finance “The Crossing Guard,” his sophomore directorial effort. But he imbues this wannabe consiglieri with an unhinged, frequently comic and regularly coked-up confidence and cockiness — a man determined to make mob bosses quiver in his wake the way he long has in theirs.

But long before David hatches Mephistophelean plans, he’s simply Carlito’s lawyer, who sits back as his client grandstands before the court. At first blush, Pacino seems to have forgotten he’s no longer on the set of “Scent of a Woman.” His confusion would be understandable. It begins much in the same formal, judicial setting in which “Scent” ended. It’s another moment where he hands seething, sneering character James Rebhorn his ass. And most obviously, it’s more of Pacino yelling.

As he delivers exposition like an overenthusiastic sommelier prattling on about oaky notes, Pacino sounds more like Lt. Col. Frank Slade than a Puerto Rican man. And naturally, because it’s Pacino, we assume Carlito must be insincerely hamming it up; there’s no way a career criminal who lifts passages from the “I Have a Dream” speech could really be this earnest about rehabilitation.

Carlito crassly co-opts words of historic importance, but the spirit in which he hijacks them is undeniable. Here’s a man who was certain he’d never again breathe a free man’s air, who understands the error of the ways that put him there and legitimately wants to put them behind him. To believe he is capable of anything makes him big, but the streets on which he’s set loose, where violence looms, are determined to make him small.

Cinematographer Stephen H. Burum and production designer Richard Sylbert aesthetically emphasize this through dynamic depth of field, thematically strategic camera placements and large-scope filmmaking. One shot captures several blocks of glorious widescreen location shooting, and another subtly frames a lackey’s holstered gun just in front of a mob boss as he spins some seemingly duplicitous jive; it’s not hard to see which one more clearly tells the truth.

But the street’s flash no longer impresses Carlito. Once he was the “J.P. Morgan of the smack trade.” Now, he’s trying to stake a $75,000 buy-in to rent cars in the Caribbean. Kleinfeld laughs at this. Buddies on the street chuckle, too. They think a dream must be framed in marquee lights and gaudily announced to the world. They dream of faster lives, but Carlito’s speed slammed him into a wall of incarceration. Carlito now has no wink, nudge or guile — a cultural Rip van Winkle with a deep-seated desire to start over somewhere else now that he’s unexpectedly awakened.

However, Carlito is quickly endangered when he accompanies his cousin Guajiro on what is said to be a simple cash-for-coke trade. Carlito knowingly laughs at the notion of “simple.” His cousin is either deluding himself that this job is somehow temporary, or the whole exchange will end in toe tags.

Quickly, Carlito assesses how this deal will go south in a way his cousin will not. Thanks to improvisation at a billiards table, he barely escapes death in a shootout and holes himself up in a bathroom. With an empty clip, he utters weary mas macho bluffs in the hopes that his bluster — and what remains of his fearsome reputation — will frighten off any remaining lackeys. Bravado is a rare dialect in the patois of Shouty Pacino, but the actor makes it sound like a native tongue.

Carlito nabs the cash and uses it to seed his stake in El Paraíso, a disco Kleinfeld has just purchased. In exchange, Carlito will keep his head down, run the club and graciously bow out once he’s got his nest egg. Between the club’s name and an “Escape to Paradise” billboard that factors into the beginning and end, the movie is more or less Carlito’s purgatory before his paradise.

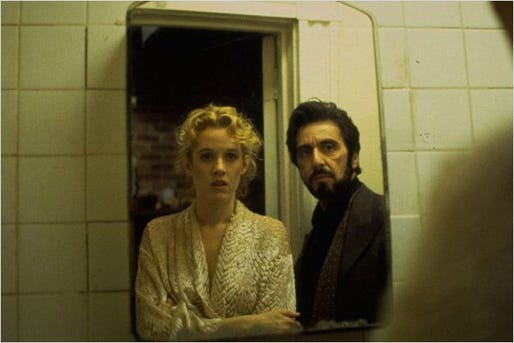

One night, he sees a dancer who gives his heart a mnemonic flutter to a paradise of the past with Gail (Penelope Ann Miller), the ballet dancer he was dating when he was incarcerated. In what he tells himself was a chivalrous act, Carlito severed this relationship like a gangrenous arm, claiming hope would have only killed him and remaining tethered to him would have only ruined her.

It’s here that De Palma trots out his hallmark Hitchcockian voyeurism, as Carlito finds Gail at a rehearsal and watches her from afar on a rooftop. Pacino has rarely looked so hapless or love-struck, soaking under a newspaper in the rain. And he gazes on her grace and beauty not with the usual menace associated with De Palma, but with unabashed love and regret, and Doyle’s score lushly stirs in the way of Bernard Herrmann’s most swooning, ornate themes.

Theirs is a tentative, delicate dance of reconciliation, but Carlito persists because Gail is the only one who looks at him not as a hero, has-been or patsy. To Gail, he’s just “Charlie,” and that’s a term of endearment which changes his name not in some sense of anglification, but a reflection of his own goal to become an fundamentally different person.

“Carlito’s Way” is as much a love story as a street-level epic. And when its protagonists’ passion finally explodes, Burum’s camera moves just as rapturously in erotic ecstasy as it does in violent agony — the camera swirling around Gail, who is the only true north Carlito has.

It’s alleged that Miller and Pacino were having an affair during the filming, and the chemistry shows — particularly in the usually milquetoast Miller. And De Palma, who regularly equates the female form with queasy, sleazy kink, achieves a sort of spiritual uplift in this film’s sensuality.

For a 2 ½-hour movie, the plot remains relatively muted until the final 45 minutes. But with so many arresting interludes and interactions that offer further insight into Carlito’s character, it never once drags.

There’s Lalin (Viggo Mortensen), a mover-and-shaker sent to prison, confined to a wheelchair and trying to save his own ass by entrapping Carlito with a wiretap. It’s odd to see Mortensen, usually a master of modulation, play so unrepentantly over the top. (His sad-sack soliloquy about his limitations, namely the way he squeaks out the word “hump,” is unforgettable.) While it seems garish, it illustrates how, had Carlito held onto hope of seeing Gail again, that he could have wound up with this wrecked body, mental anguish and futile desperation.

Then there’s Benny Blanco “from the Bronx” (John Leguizamo), an up-and-comer who tries bandaging his disrespect to El Paraíso’s staff with overflowing affection for Carlito. Benny brings out the remnants of puffed-up posturing in Carlito, namely because people say he reminds them of him at that age. Unwilling to be sunken to his level, Carlito asserts himself, then implements a measure of mercy, that will unexpectedly come back to haunt him.

And, most destructively, there is Carlito’s unwavering, but unwise, loyalty to Kleinfeld, whose wide lapels are about to get snagged on the wrong line. We learn he stole his $1 million investment for El Paraíso from Tony Taglialucci, a mob-boss client doing time on Rikers Island. To save his skin, Kleinfeld agrees to pilot a boat to a buoy and pick up Taglialucci, who will swim there after paying off a guard to help him escape.

De Palma enshrouds the scene in thick, near-mythological fog, and when Kleinfeld splits Taglialucci’s head open, he and Carlito have truly crossed the Rubicon. From there, the film enters a headlong scramble as Carlito attempts to escape with Gail, now pregnant, and exact revenge against Kleinfeld, whose scuzzball duplicity has only multiplied.

It culminates in the film’s best-remembered scene, as the Taglialuccis pursue Carlito through Grand Central Station, where he’s trying to meet Gail for a train out of town. This remains as masterfully choreographed and cut together as any you would see today, with strategy behind every chess-piece move and carefully integrated flashes of clock to convey Carlito’s rapidly dwindling timetable. The approach even aligns thematically with Carlito’s new outlook on life. By simply fading into backgrounds, he almost escapes scot-free, and his eventual use of gunfire is simply a last resort.

So exciting is Carlito’s fleet-footed race to the train, so close is he to actual, tangible freedom that, for a few seconds, you might forget about the bullets coming for him. But there they are, this time rendered in full-fledged color before he turns his bloodstained cash over to Gail and insists that the two of them left get out.

Up to then, we’ve never seen Carlito hang his hat at any place he calls his own. If not at the club, he’s at Gail’s apartment, Kleinfeld’s house, bumming around New York. Home, it seems, is this grave he’s approaching — a threshold he thought he’d have crossed much longer ago. As Pacino’s soulful eyes fill the screen — as wide-eyed and wondrous as Tony Montana’s were beady and enraged — it’s a reminder of the wily expressiveness modern-day Pacino brings to his best parts. And that for every “Jack and Jill” or “The Recruit” there may yet be, he is, was and always will be a legend.

As Carlito turns his final gaze toward an “Escape to Paradise” billboard — an advertisement for a Caribbean paradise that’s as ominous as “The Great Gatsby’s” tattered T.J. Eckleburg advertisement — he sees the beachside woman in the still photograph start to dance a la Gail. The credits roll, and those who bailed would understandably assume the worst, that this is the final, feverish dream of a dying man — an ideal and not a reality. But stick around, and you see Carlito, Jr. running up to her on the sand.

It’s natural for anyone who’s seen a De Palma movie to suspect this is cruel cynicism — twisting the knife on a life that will never be and besmirching an epic pop song like Joe Cocker’s “You Are So Beautiful” in the process. But that the camera lingers for so long on this exuberant dance suggests this is an unabashedly full-hearted finish suggesting love and legacy have truly carried on. The song is as much an ode to the new life Carlito briefly enjoyed and, in death, provided for others as it is to the woman he loved.

This scene suggests he, and those he loves, are free in the way he’d hoped they could be at the courthouse — if not in the ideal way he’d intended. It’s sad without feeling like tragedy, this tale of a man who ultimately reconciles his passion for living with the remnants of a code predicated on death. De Palma isn’t being nihilistic, fetishistic or misogynistic. He’s being humanistic. In “Carlito’s Way,” as it does in so few movies, the end truly feels like the beginning.