Class of 1994: "Fear of a Black Hat"

In the “Class of …” series, we take a monthly look back at films celebrating either their 20th or 30th anniversary of initial release this year — six from 1994 and six from 1984. The rules: No Oscar nominees and no films among either year’s top-10 grossers.

A next-to-no-budget gangster-rap mockumentary, “Fear of a Black Hat” liberally spits foul, funny lyrics in spoofy songs that are by turns incisive (“Guerrillas in the Midst”), imitative (“Ice Froggy Frog") and infantile (“Fuck the Security Guards”), but always incendiary. Yet when you look back at the survivors among those whom the film savages — and the film is nothing if not one long roman á clef roll call — this innocuous little line seems to best sum up a certain subtext lurking beneath the silliness: “The good old days are a brother’s worst enemy.”

Ice Cube once lobbed the inimical introductory verse of N.W.A.’s “Fuck Tha Police,” but he’s since traded caustic commentary for cuddly comedy. Ice-T shared a similar sentiment … and now pulls down paychecks playing a policeman. And Dr. Dre, who rapped about razing the establishment with riots, is now one of its billionaire buttresses — selling his Beats Electronics business to Apple for 10 figures this week.

That’s not to demean or diminish these artists or slap them with the reductive label of “sellout.” But it does illustrate the inverse relationship of rage and age relative to success. Save Eminem, what crotchety fortysomething rapper remains commercially relevant? Plus, it’s the age-old question of credibility: When you have GDP money, is being pissed-off a put-on? I say so what if Cube, T and Dre have let the past propel them to success, but also let it take its place in their history, look forward and continue to cash in. Money wasn’t their only motive, just as it’s (generally) not ours. Their particular occupation happened to be offering profane, blunt, front-line commentary on inner city violence, oppression and confusion — a window into a world most of the country might not have wanted to see. Only in the wake of their gangster-rap template did the knockoffs who were all about the flash and finances start to make their way into the industry.

Yes, “Hat” takes its jabs at Cube, T, Dre, N.W.A., Public Enemy and a host of socially conscious rap forefathers. But it reserves its real fury for those who latched onto the sound and/or the culture solely to make money. Facing a seemingly unsquashable beef, the film's fictional rap group, N.W.H., chooses the unsustainable short-term success of reuniting. They want that “old, rickety white-people money” and are OK with “artistically taking a step backward to move forward.” Such pointed potshots at posing for the pursuit of cold hard cash — of which there was much in the real-life rap world of the 1990s — only make “Hat” more hilarious. And although it’s the (much) lesser seen of the early-’90s gangster-rap spoofs, it’s easily the sharpest.

“Hat” is the brainchild of writer, director and star Rusty Cundieff — a comedian who cut his teeth with fellow hyphenate Robert Townsend in 1987 by co-starring in Townsend''s “Hollywood Shuffle.” Following his screenplay credit on a sequel to the sleeper hit “House Party,” Cundieff took on triple duty for “Hat" and more or less filmed it at the same time as “CB4” — a semi-similar Universal Studios-produced film starring Chris Rock with which "Hat" even shares an actor (Deezer D). Technically, “Hat” struck first, at 1993’s Sundance Film Festival. But “CB4” hit theaters weeks later — earning nearly $18 million — while “Hat” languished for 17 months, dumped in the summer of 1994 to earn $238,000.

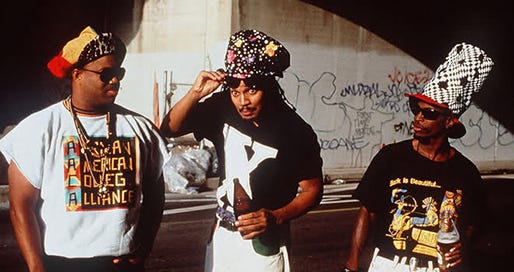

“CB4” follows a more conventional caper plot: A would-be rapper assumes the persona of an imprisoned criminal, drawing the government’s ire, the media’s attention and the wrath of the thug whose life he stole. “Hat” is much rowdier and more purposefully ramshackle. It’s technically a film within a film directed by Nina Blackburn (Kasi Lemmons), for whom the footage is a thesis for a sociology doctorate. She’s following N.W.H., or Niggaz with Hats. This trio believes its headgear symbolizes the taking-back of power sapped from slaves whose heads roasted hatless under scorching suns. (Besides the obvious N.W.A. connection, N.W.H. also stands in for Public Enemy and 2 Live Crew at various stages of the movie.)

Best known for playing the flamboyantly gay Tri-Lamb Lamar from “Revenge of the Nerds,” Larry B. Scott plays Tasty Taste. He’s the Eazy-E stand-in, with a shot of Flavor Flav, as the group member with a past history of “pharmaceutical distribution” and a plethora of weapons. Ice Cold (Cundieff) is a composite of Cube, T, Dre and Snoop Dogg, who comes to savor a more solo spotlight. Meanwhile, DJ Tone Def (Mark Christopher Lawrence, most recognizable as Big Mike on NBC’s “Chuck”) tries to be the bedrock of a group clearly erected atop highly active emotional fault lines.

In verite style, Blackburn follows the trio while they’re on tour, and these interviews are interspersed among N.W.H. videos, backstage shenanigans and onstage incidents. Threatened with obscenity charges if they don’t change “Grab Your Shit” to “Grab Your Stuff,” the trio happily complies. But aggressive crotch clutches lead to injury and utterance of the offending words anyway.

Nina probes them about antagonistic, unreleased tracks (“Kill Whitey,” a proxy for Ice-T and Body Count's “Cop Killer,” even if it’s purportedly about one particularly bad person named Whitey), attacks their misogynist mindset (a smile makes a woman think “she got you,” Ice Cold says, so if you’re predisposed to smile, “you best to kick that shit doggie-style”) and skeptically questions their assertion of political undertones in every song…even in the sexually unctuous “Booty Juice.”

Of that number, N.W.H. argues that the butt stands for society, which must be fully opened and expanded to tap its true potential. When it comes to generous guffaws, this ascription of sociological meanings to songs about sex is the film’s greatest running joke; N.W.H.’s white managers whose mortality rate matches that of Spinal Tap’s drummers runs a close second, and is a fine homage.

The musical production also captures the day’s prevailing pop sounds, from sinister synthesizer drones to canned uptempo beats. There’s as much verisimilitude in the videos, from the ironically enticing visuals of “A Gangsta’s Life Ain’t Fun” to the Sir Mix-a-Lot-ish innuendo of “My Peanuts” (which, as Ice Cold sensitively scolds, is not to be confused for “My Penis.”) And while the “Booty Juice” clip then seemed an excessive parody of Wreckx-n-Effect’s poolside party in “Rump Shaker,” its literal tapped-ass absurdities now seem to presage Nelly’s real-world “Tip Drill” video — in which the rapper swipes a credit card through a butt crack as payment for twerking.

If “Hat” stumbles anywhere, it’s in a second-act subplot about a gold-digger who comes between Ice and Tasty and, eventually, splits the group up. Still, it’s only a short stretch of an otherwise efficient 82 minutes that leads to even more uproarious moments once all three members go solo.

Tasty Taste takes a page from LL Cool J with “Granny Says Kick Yo Black Ass.” Tone Def chills out new-age style as part of the New Human Formantics — a fake band name no less goofy than real bands Digable Planets or P.M. Dawn (whose meditative “Set Adrift on Memory Bliss” is immaculately parodied, down to Lawrence’s chilled-out cadence).

And Ice Cold’s explanation of activist underpinnings in a song called “Come Pet the P.U.S.S.Y.” is one of the decade’s funniest bits. Plus, the song itself takes dead aim at the controversy behind C&C Music Factory’s “Gonna Make You Sweat (Everybody Dance Now)” and how a willowy Asian singer can somehow “sing black.”

Cundieff’s follow-ups — the underrated horror anthology “Tales from the Hood” and the romantic comedy “Sprung” — were modest hits. But his later TV work with Dave Chappelle on “Chappelle’s Show” best hearkened back to the subversive fearlessness he wore so well in "Hat." It lampoons the luminaries, yes, but Cundieff gives their authentic anger, which came from a real place, the benefit of gentler nudges. He reserves his greatest fury in lambasting the losers who embraced the ethos of gangster rap to build a bank account, not let loose a battle cry.