Convoy (1978)

Whatever you want to say about Sam Peckinpah, the quintessentially American director was not a cuddly guy. His films were about the intersection between the structure of society and the violent impulses buried not so deep in our individual souls. Peckinpah peered into the carefully constructed order humanity wears like a tidy suit and saw the raw, writhing heart of chaos hammering away beneath.

After the blood-soaked glory of "The Wild Bunch," Peckinpah's filmography become more and more uneven as time went on, reportedly due in part to substance abuse. By 1978, he was a wreck in a need of a job, so "Convoy," a movie based on a country-and-western gag song, was the best he could hope for. According to author David Weddle, Peckinpah was so far gone that his friend James Coburn was brought in to help out and ended up directing much of "Convoy" himself.

The final product is an odd mix of comedy and outrage, hijinks and bloodshed. It's more interesting as a historical document of its time than as a compelling piece of narrative fiction.

"Convoy" arrived at the height of the trucker boom, in which the pilots of massive semi-tractor trailer trucks or muscle cars were idolized as lovable outlaws of the road, fighting onerous cops and the outrage of the 55 mph national speed limit.

"Smokey and the Bandit" had come out a year earlier and was a big hit, followed by a spate of open road projects, from "Cannonball Run" to television's "B.J. and the Bear," which, God help me, I watched religiously as a kid. At the age of 10, I even horrified my teachers and parents by putting down "truck driver" as my career goal. Considering the state of the whole journalism thing, trucking is practically as safe as government bonds by comparison.

I think in the wake of Watergate, the oil crisis driving people into chintzy little cars and a general feeling of malaise, Americans loved the idea of sticking their collective middle finger at symbols of authority. It was an age in which the political unrest of the 1960s had trickled down into the mainstream of the '70s, as the Baby Boomers settled into careers and marriage but still wanted a little rebellion in their lives.

Police officers in these sorts of highway adventures are invariably depicted as old, fat, corrupt and possibly brutal representatives of the old order. Jackie Gleason found a second lease on his career as the Smokey of "Smokey and the Bandit," and a man of similar acting experience and girth, Ernest Borgnine, was brought in to play the heavy in "Convoy."

Story-wise, the screenplay (by Bill L. Norton) is pretty spare. Martin "Rubber Duck" Penwald is an independent-minded trucker who runs afoul of some lawmen abusing their positions, stands up to them and then spends the rest of the movie running away. Other truckers soon join in, forming a convoy of 100 or more vehicles riding roughshod through roadblocks, whose destination and shining noble purpose are never really made clear.

Whatever narrative thread is pretty much supplied by the C.W. McCall song, right down to the name of the protagonist. The film also is notable for incorporating the CB radio lingo prevalent in the era, starting with the colorful names (or "handles") the users give themselves.

For instance, Burt Young's character dubs himself "Love Machine" despite looks more worthy of the moniker his fellow truckers gift him, "Pig Pen" (also due to his cargo of live, smelly hogs). Sheriff Lyle Wallace (Borgnine) uses his CB affinity to impersonate a trucker, luring them into his speed traps, where he then extorts bribes in lieu of black marks on their driving record.

After several years away from movies, Ali MacGraw unwisely chose "Convoy" to be her comeback vehicle. It's an odd choice, especially since her character doesn't have any kind of backstory, or motivation, or really a reason for being there. (I didn't even think she had a name, though various sources credit her as "Melissa.") She's driving an expensive sports car when we first meet her, which she then sells so she can ride along with the Duck.

She does have a high-end camera she uses to document the convoy when it starts to become a folk sensation, attracting the attention of the media and the ambitious governor (Seymour Cassel), who wants to use the truckers' plight to springboard himself into the U.S. Senate. For a moment, it seems like the story will spin into a tale about disillusionment, as even Melissa appears ready to sell out her access to Rubber Duck for a few bucks. But then Sheriff Lyle kidnaps/arrests Duck's friend Spider Mike (Franky Ajave), prompting a rescue attempt that leads to a predictable showdown.

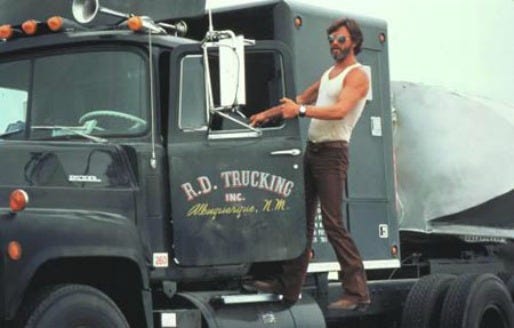

Kris Kristofferson has a natural ease in front of the camera that serves him well in the role of the Rubber Duck. He's depicted as a natural peacemaker, willing to accept police malfeasance as long as it doesn't edge into brutality; at that point, he's ready to fight back and accept the consequences. When he's held up as the leader of a great movement, the Duck demurs: "I'm not the leader. I'm just up front."

Kristofferson, who got his start as a musician, was a throwback type of movie star. Unlike the sensitive, talkative types who tended to dominate the box office during that period, Kristofferon was taciturn and laconic. Some even dubbed his acting style wooden, though I would call it more minimalist than anything else. He liked to let his pauses between lines speak more than the words he uttered piecemeal.

I'd like to make note of the tans the stars wear in this film. Kristofferson spends a good portion of the movie shirtless, revealing the lean, muscular torso that helped propel him to stardom. He's also burnt to a nice medium brown, a popular look at the time (which I, with my nearly translucent northern European flesh, have never been able to achieve). MacGraw, on the other hand, looks practically deep-fried to a unhealthy crispiness. Gosh knows how many Boomers would end up with carcinoma as a result of the fad.

The film went on to be the biggest box office hit of Peckinpah's career, though it was the beginning of the end for him. Word about his (non) work on the film soon spread around Hollywood, and job offers dried up. He would only direct one other feature, the lackluster spy thriller "The Osterman Weekend" five years later.

"Convoy" was a low point on the long, lonely road to even lower.

3 Yaps