Deliverance

Every critic I know considers Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Godfather” to be the best picture of 1972. Except for me. For that year, I proudly choose John Boorman’s adventure thriller “Deliverance” as not only the best film of the year, but one of my 10 best of the entire decade. Based on William Dickey’s 1970 novel of the same name, “Deliverance” follows four city men from Atlanta on a harrowing weekend canoe trip that changes their lives forever.

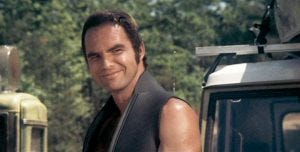

Ed, Lewis, Bobby and Drew are southerners, to be sure. Some might refer to them as “good ol’ boys.” But they are cultured. We learn Bobby is an insurance salesman, and we assume the others are educated as well. Ed and Lewis (Jon Voight and Burt Reynolds) are experienced outdoorsmen who decide to canoe a potentially treacherous stretch of a fictitious Appalachian river before it is dammed to create a new reservoir. Bobby and Drew (Ned Beatty and Ronny Cox, each making their film debuts) are novice adventurers, but friends of the other two who accompany Ed and Lewis for the weekend.

Things begin to go awry when the four stop for gas at an isolated service station along a section of rural mountain road. In the film’s most famous scene, Drew plucks out a simple melody on his guitar, only to have his notes mimicked by a local country boy with a banjo. The two bat the tune back and forth for a minute before launching into a whirlwind of music that Drew (apparently an experienced guitarist) finds difficult to follow. Excited about the possibility of playing another song together, the hillbilly boy turns his head in refusal.

This scene accomplishes two things. First, it establishes the four friends as outsiders in rural Appalachia. And second, it sets up the simple canoe trip as one that will take the men into unknown territory. Much as Drew doesn’t know where the country boy will take the melody, the city men don’t know what the resentful locals might have in store for them.

Furthermore, the mesmerizing guitar / banjo battle was possibly quite instrumental (pun intended) in making “Deliverance” one of the highest-grossing motion pictures of the year. You see, that music became the hit song “Dueling Banjos,” an instrumental hit so big it would have spent the entire month of February 1973 at No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart had Roberta Flack never released “Killing Me Softly With His Song.”

Following a long introductory sequence in which we get to know the personalities of the four men, tragedy strikes when Ed and Bobby dock their canoe on a riverbank to take a quick break. They are assaulted by two toothless yokels, in one of the most chilling scenes in motion picture history. These two are so distastefully provincial one wonders if they have ever been counted in a census. Lewis and Drew arrive to chase the hillbillies back up the mountain from whence they came, but not before Lewis kills one of them with his bow and arrow.

Then, much as in the recent “Nocturnal Animals,” most of the meat of the picture takes place after the climactic scene. It is at this juncture where we become absorbed in the men’s fate, as they discuss whether to take the dead body with them to turn into the authorities, or bury it — under the assumption that they could never receive a fair trial from a jury of inbred bumpkins, half of whom are probably related to the deceased.

Without spoiling the climactic third act, suffice to say the canoeists eventually transcend an unexpected rapids that destroys one of their canoes, and further expands their dilemma. Upon arriving at their destination (the fictional town of Aintree), the men must explain their adventure to a disbelieving sheriff (Dickey himself) as they attempt to reintegrate into society from what feels like the weekend from hell.

Besides the protracted denouement, Boorman (a great director of adventure films — sort of a more polished version of Sam Peckinpah) makes several directorial choices that I love. First is the way life in the “outside world” seems to progress as though nothing has happened. One scene I’ll always remember features an Aintree local driving the men to the sheriff’s office. Their vehicle is moving slowly because it is following the local church — a building so small a truck is transporting it to higher ground to make way for the new reservoir. The driver comments that the townsfolk were forced to move the church. Having just experienced a weekend they’d like to forget, the city men couldn’t care less about the church; but it symbolizes the backdrop of “progress” depicted in Dickey’s novel — that which is beneficial to city dwellers (a new water supply) destroys the lifestyle of the country residents. By attempting to become country residents for a weekend, four city slickers endure rejection they’ve never felt before.

Second is the way Boorman employs great actors and then lets them act. Sometimes we’ll hear a basketball player describe his coach as a “players’ coach” — meaning he allows the players to call their own plays depending on the circumstances of the game. Likewise, Boorman is an “actors’ director.” Voight and Reynolds shine in the best performances of either of their careers. Before he became a good-ol’-boy caricature, Reynolds was an excellent actor, and here he plays the “real man” character with aplomb and assuredness, without going overboard. His is an intelligent character, yet with just enough vulnerability to be absorbing. Voight’s character is the levelheaded one who also harbors a strong sense of compassion. His Ed is the liaison between Lewis and the newbies. In what is actually the more difficult acting assignment, Voight's Ed keeps Lewis in check, if you will. In one of the film greatest lines, Lewis utters, “I’ve never liked insurance. There’s no risk.”

“Deliverance” is not necessarily an easy film to watch. But it is completely spellbinding. The first time I saw it, I wanted to become invisible while the theater steward cleaned the floor, so that I could immediately watch it again. It is one of the triumphant masterpieces of the greatest decade of moviemaking — back when directors tried to make the best films rather than the biggest hits. “Deliverance” was both, and because it was one of the highest-grossing pictures of the 1972 / 73 season, it is sometimes given short shrift as a classic. That’s a shame because this captivating thriller still stands the test of time. And that’s why it’s this month’s Buried Treasure.

Andy Ray's reviews of current films appear on http://www.artschannelindy.com/