Dirty Dancing (1987)

"Dirty Dancing" may just be one of the most seminal garbage movies ever. But, garbage it is.

Somehow I missed seeing this film, a smash success when it came out in August 1987. The omission is perhaps not surprising: I had just gone off to college, and it looked to be a sappy romance dressed up against the backdrop of dancing, something in which I have never had an iota of ability or interest. (No surprise that "Footloose" and other dance flicks of the era also escaped my contemporaneous notice.)

It's about a sweet Jewish teen girl in the early 1960s who falls for the bad boy dance instructor at Kellerman Hotel, the posh Catskill Mountain resort where her family is turning "summer" into a verb. He teaches her to dance, and to stand up for herself, and she teaches him that nice Jewish girls make good lays if you have feathered '80s hair in a story set in 1963.

I kid, I kid... but not by much.

The movie, directed by Emile Ardolinio ("Sister Act") from a script by Eleanor Bergstein, gleefully mashes up pop culture references between the two decades -- not so much an homage as a reconfiguring of the past to make it more palatable to modern audiences.

That's best encapsulated by the film's theme song, "(I've Had) The Time of My Life," to which the main characters dance in the big scene at the end, brazenly showing off their forbidden love to the world. It sounds very much like a 1987 pop song, not even attempting to mimic the rhythms and instrumentals of the era. It wound up a chart-topping hit, and won prizes at the Academy Awards, Golden Globes and Grammys.

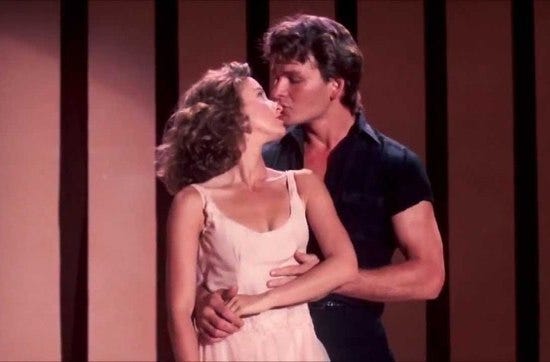

Speaking of the Big Dance: the scene where Johnny Castle (Patrick Swayze) strides up to the table of Frances "Baby" Houseman's (Jennifer Grey) family and announces to her dad (Jerry Orbach), "Nobody puts Baby in a corner," has become a certified Iconic Cinematic Moment.® It's been endlessly referenced and parodied, and even today people toss it around as a phrase of empowerment.

Coming so very late to the game, I have two observations:

The moment makes no sense. Baby is sitting against a wall on the side of Kellerman's ball room, not in a corner. She's next to a stone column that sticks out about 8 inches, but it's not like she's deeply ensconced in shame and shadows. And her dad didn't order her to sit there; she's sitting next to her mom (Kelly Bishop). Presumably, she chose the spot herself, leaving the seat closest to the stage for her sister, Lisa (Jane Brucker), who was part of the summer-ending show.

When Baby's father (Jerry Orbach) briefly stands up to object, there's an awkward do-si-do where Johnny takes Baby's hand, negotiates her around dad and they stride off together to the stage. Orbach, a tall Broadway actor, towers over the much shorter Swayze in a way not favored for screen protagonists. In other scenes where the two men confront each other they're eye-to-eye, so I suspect the old reliable "apple box trick" was employed.

The film was a breakthrough for Swayze, Grey and Orbach, who each saw their acting careers launched to previously unknown heights. Orbach, the stage veteran, suddenly found himself an in-demand presence for film and TV roles in his 50s and 60s. He became so popular playing cops and heavies, mostly notably as Lennie Brisco on "Law & Order," that later on audiences were baffled to discover he was a song-and-dance man with great pipes, as he showed off playing Lumiere in "Beauty and the Beast."

Grey, who previously had small roles in "Red Dawn" and "Ferris Bueller's Day Off," soon saw her star fading, largely resigned to television movie roles amid a pair of botched nose jobs that (in)famously left her unrecognizable. It was an odd choice to make: Her petite, slightly hooked schnoz is the very feature that made her stand out from other actresses of the day, giving her an authentic, relatable look. But she was hardly the first starlet to be undone by ill-advised visits to the plastic surgeon.

(Though I use "starlet" in the most generous sense. As is Hollywood custom, Grey was a decade or so older than her teenage character.)

Swayze went on to become one of the top leading men of the late 1980s and '90s, ping-ponging back and forth between romance pictures ("Ghost") and ridiculous action flicks -- "Road House" and "Point Break," two more movies that have gone on to cult status despite having charms that elude me.

A trained dancer via the Joffrey Ballet, Swayze won the part of Johnny over the much-younger Billy Zane, who apparently couldn't dance a lick. He and Grey butted heads on the set of "Red Dawn," but they dance beautifully together. And while their dancing montages are loaded with schmaltz -- Johnny playing air guitar to her feline stalking representing the zenith -- it's hard to deny the onscreen heat between them.

The choreography (by Kenny Ortega) plays pretty well to these untrained eyes. The story is set in motion when Johnny's usual dance partner, Penny (Cynthia Rhodes), is felled by a botched abortion, and Baby offers to sub in. Johnny teaches her the ins and outs of the mambo and other conventional steps shown off at Kellerman's, as well as the more "dirty" dancing that the resort workers engage in at private parties.

This seems to consist entirely of the two dancers stepping between each other's overlapping legs, so they can grind their crotch against the other's thigh. Ah, l'amore.

Interestingly, Baby does not turn into a spectacular dancer overnight. She learns enough in a few days of cramming to perform a passable mambo for a gig at another resort, though she makes a few mistakes and is too afraid to execute the dramatic lift. Saving that for the last scene, I suppose.

There really isn't much plot other than I've outlined here. There are some jealousies and intrigues that pass via secondary characters, notably Robbie (Max Cantor), the snotty medical student who knocked up Penny, and Neil Kellerman (Lonny Price), the also snotty son of the resort owner (Jack Weston) who's in training to take over the business and has eyes for Baby.

Baby's dad is a hardworking, upstanding doctor who is beloved by his youngest daughter. When she asks him to treat Penny in secret, he does so but comes away with the assumption that it was Johnny who impregnated her. Displaying classic "wrong side of the tracks" pride, Johnny allows this to pass, used to being looked down upon. When and Baby begin their secret affair, their biggest challenge is she won't stand up for him, or herself.

Well, that and his side gig as a male prostitute.

While it's never overtly depicted, it seems that Johnny's true role at the resort is not just to teach middle-aged Jewish ladies to dance, but to have sex with them for money. Sometimes this is done discreetly, but in at least one case, it's actually the husband paying off the dance stud to bed his wife and keep her out of his hair so he can play cards. This is the sort of scenario that has only ever existed in a Hollywood movie.

It's curious that Baby never seems bothered by Johnny's side hustle as a hustler. (Or the danger of STDs... a curious thing for a physician's daughter.) At one point in the movie Johnny announces to Baby that he's giving up sleeping with those other women for cash, and it's laughably depicted as a poignant moment.

One other thing struck me about the movie: the lack of commentary on the schism between the Jewish clientele vs. the gentile staff at the resort. The cultural references are not exactly hidden -- Catskill Mountains, the emphasis on girls marrying lawyers or doctors, the surfeit of "-man" surnames -- yet it's never brought up explicitly as another reason to drive these star-crossed hoofers apart.

As you've probably detected from the tone of this essay, I don't have a lot of respect for "Dirty Dancing." Nobody expected it to be anything other than what it is: a corny, low-budget romantic musical featuring nostalgic pop tunes and some slightly sweaty, PG-13-rated naughtiness.

It became something far more, and our popular culture is lesser for it.