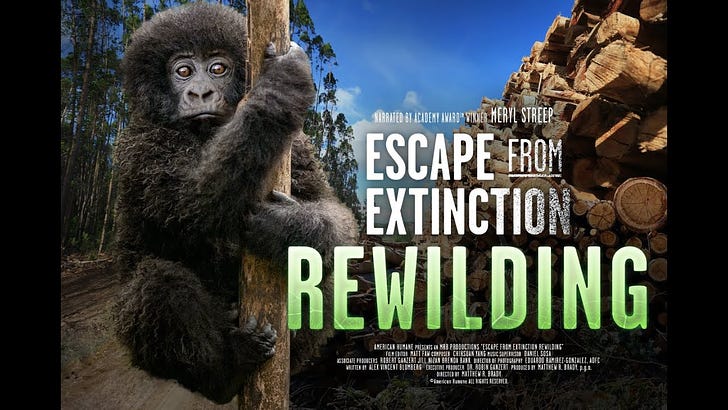

Escape from Extinction Rewilding

This eye-opening environmental documentary doesn't just lament the damage humans are doing, but showcases real world solutions in turning developed areas back into natural habitat.

I’ve seen plenty of environmental documentaries in my time, and they can be a pretty depressing affair. They are in danger of coming across as bitter scolds, lamenting the damage humans are wreaking on our world without offering realistic solutions other than “fewer people.”

That’s why “Escape from Extinction Rewilding” is so refreshing. Produced by American Humane (not to be confused with the Human Society) as a follow-up to their 2020 documentary, it looks at real-world efforts happening right now to take developed or blighted areas and turn them back into viable habitat for threatened species.

Narrated by Meryl Streep, it’s an eye-opening experience that leaves you with a sense of dire urgency, but also hope and determination.

It starts off with the usual scary stuff: 1 million species are in danger of becoming extinct in the near future; one-quarter of all species on earth could eventually vanish forever, etc.

“We’re in a war, and most people don’t even recognize the war exists,” says one of the many interviewees, nearly all of them heads of environmental organizations, scientists or people working in the field.

(Among them are Bill Street of the Indianapolis Zoo.)

But director Matthew R. Brady, who also helmed “Escape from “Extinction,” and writer Alex Vincent Blumberg paint an incredible picture of the activities of “rewilding” that in some cases of have completely transformed areas and brought species teetering on the bring of extinction back to viability.

It’s founded on the base of ecosystem-level conservation, which recognizes the delicate balance between predator and prey, flora and fauna. Remove a few species, and it upsets the whole construct. One expert aptly compares it to a game of Jenga — eventually, if you pull out too many bricks the whole thing comes crashing down.

For example, Rwanda was torn apart by civil war in the 1990s, leading to hundreds of thousands of refugees pouring into previously protected areas like the Akagera National Park. Animals were hunted for food or their valuable horns. Disaster loomed.

But over the last 30 years, scientists painstakingly reintroduced lions, rhinos, elephants and other large mammals back into protected areas, making sure to pluck variations from all over Africa and even zoos to ensure there was enough genetic diversity.

As a result, Rwanda’s eco-tourism industry has exploded. And they turn over 10% of those revenues to the locals so they reap the benefits and understand that these species are helping them, too.

Similar things are happening nearby at the Volcanoes National Park, made famous by the work of Dian Fossey with the mountain gorillas. They have also been hunted and their habitat squeezed, but new efforts have seen a major rebound, assisted by carefully monitored tourism. (Something Fossey loathed, btw.)

The blue-throated macaw has been helped by the installation of nest boxes that simulate their favored tree for breeding hatchlings. The reemergence of sea otters along the Pacific coast of North America has helped lower acidification of the ocean waters because they eat the sea urchins that consume the kelp forests which process CO2. Replacement plantings for disappearing seagrass have helped the Florida manatee swell their ranks.

Interestingly, sometimes rewilding means culling rather than just reintroducing species. Invasive creatures, often brought in by humans for a specific purpose — such as to eradicate a pest species — wound up causing harm and their populations spiraling out of the control.

Some of these activists even advocate for sustainable hunting — usually a dirty word to environmentalists — to help keep down invasive populations and responsibly use the meat and pelts for indigenous humans.

In other cases, species are translocated from a place where they are overabundant to one where they are scarce. It can be hard to believe, but it’s possible for a species to be endangered in most of the world, but a nuisance in another ecosystem. For example, rhinos raised by Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar for his private zoo got loose and now run rampant.

It’s satisfying that these scientists admit that sometimes they get it wrong, such as introducing foxes in Australia to get rid of rabbits eating crops, and instead wiping out the native bandicoot, one of the tiniest marsupials. But they’ve learned from those mistakes, so rewilding has become more and more refined.

“Escape from Extinction Rewilding” is, of course, as much a work of activism as documentary filmmaking. Expect the usual appeals for sustainable behavior — and donations — in the closing credits. After such a compelling vision of positive change, I found myself not minding.