Hellraiser (1987)

Given their dire, morbid subject matter, horror films may not seem like the best representations of mankind for aliens to study. However, “Hellraiser” is one film I would leave in their hands, as it perfectly juxtaposes our collective morbid curiosity and hope for a life without monstrosity and violence.

Due to the film's sadomasochistic imagery and legions of pierced, tattooed fans, most dismiss it as a grungy, nihilistic piece of punk horror. However, with its eerie rustic setting and mounting sense of dread, it is more akin to the romantic Universal Studios monster movies of the 1930s and '40s.

The story revolves around the twisted romance between bored housewife Julia (Clare Higgins) and her husband's hedonistic brother Frank (Sean Chapman). When a skinless Frank returns from a netherworld opened by an ancient puzzle box, he enlists Julia to help him regenerate, namely by seducing men from whom he can absorb flesh and energy. Stick with me; it gets better.

While Frank waits in the attic of her English cottage like a Victorian-era monster, tension grows between Julia, her husband, Larry (Andrew Robinson), and his teenage daughter, Kirsty (Ashley Laurence). Eventually, Julia's secrets are revealed, and Frank slowly tears the family apart.

Frank is a reflection of horror fans and moviegoers in general in that he takes the emotional risk of opening Pandora’s Box, unleashing forces of pleasure and pain.

While he embodies the basest instincts of filmgoers and society as a whole, Kirsty represents the most noble, deciphering the horror around her rather than surrendering to it. These characters’ actions — Frank’s indulgence in fear and Kirsty’s detachment from it — reflect the process of catharsis that all great horror films provide.

Horror is the most imaginatively therapeutic genre, as it holds a funhouse mirror up to everyday fears and contemporary societal issues. In 1982’s “The Thing,” for example, an infectious alien serves as a symbol of disease (specifically AIDS) and our nation’s warped view of those afflicted with it. And in 1979’s “Dawn of the Dead,” writer-director George Romero uses zombies attacking a shopping mall as symbols of consumerism, representing the mindless, materialistic masses of America. As director Tobe Hooper ("The Texas Chainsaw Massacre," "Poltergeist") said, “We live in messed-up times and people are scared and angry. This form of cinema (horror) helps us get some of the poison out of us."

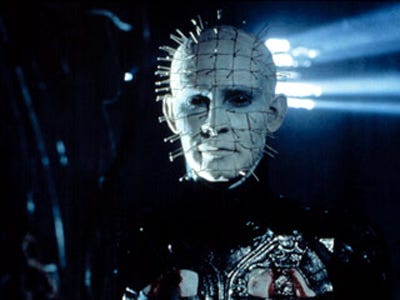

Pinhead, the soul harvester hunting Frank, is an embodiment of the genre's creative magic. A visually arresting icon, he evokes the same visceral, knee-jerk reaction as horror films themselves. With nails protruding from his face, he is Frank's masochism personified.

Pinhead is also testament to the genre's staying power as, like most screen bogeymen, he is embedded in our collective consciousness. In addition to the character's original, indelible design, credit actor Doug Bradley, who smolders with menace beneath that ghostly makeup. Like horror films themselves, he accentuates a sense of humanity beneath his cold, foreboding exterior, making Pinhead all the more engaging. The character's darkly comic, oddly empathetic nature also stems from writer-director Clive Barker's brilliantly perverse imagination.

"Hellraiser," Barker's best film, is at once intimate and explosive — a family drama in which family skeletons come flying out of the closet ... literally! This seamless blend of wild fantasy and harsh reality is precisely what makes the horror genre great. It coats real-world fears (in "Hellraiser's" case, family destruction) with sugar (dazzlingly macabre imagery) to make the medicine go down.

Watching horror films like this, you will discover, as “Hellraiser’s” Kirsty does, that if you dig beneath the blood-splattered surface, you will gain understanding of the unspeakable and thereby conquer your fear of it.

While artists, especially horror filmmakers, use shock value to draw audiences to their work, they also expect them to dig deeper and uncover the more important issues being raised. You'll be more than happy to do that for Clive Barker here.