Hidden Figures

A muckety-muck in "Hidden Figures" morosely muses that if Russia wins the Space Race, the only logical next step is nuclear warfare rained down upon the U.S. from galactic heights.

An easy hindsight laugh-line a few years (hell, a few weeks) ago, the bit plays today like the sort of dangerous speculation that will make a lot of socially conscious ’60s-set films feel harrowingly new again – however unintentional and even when as comparatively calm and crowd-pleasing as “Hidden Figures.”

Adapted from Margot Lee Shetterly's nonfiction book about African-American female mathematicians at NASA who calculated flight trajectories for Project Mercury, Apollo 11 and the dreams of future women who looked and thought like them, “Hidden Figures” sheds light on good people who worked at the intersection of civic duty and civil rights and persisted against the double-edged sword of progress. (All the white men in the room seem to sense their day of reckoning with technology is also nigh.)

What could have been archaically medicinal instead boasts more spikiness than sentiment and – aided by Pharrell Williams’ anachronistically brassy and bouncy score and songs – showcases unexpected cinematic pizzazz and panache.

“Hidden Figures” recognizes the inherent risk in running from lives that have been made, in their own ways, to be as comfortable as they can – all the more difficult for women marking time in a status quo to which the powers that be have shunted them, and even then begrudgingly. Plus, the film’s breathing room is generous for each woman’s joys and struggles of how they juggle ambition and apprehension to land without either simplifying or weakening them.

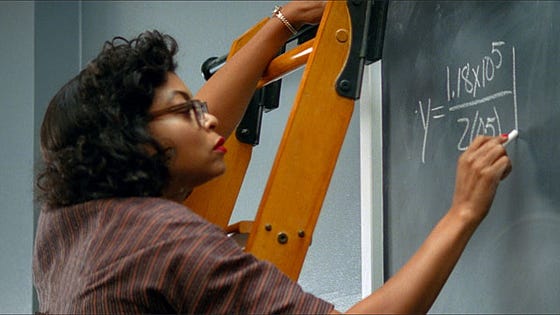

Katherine Johnson (Taraji P. Henson) is a mathematical prodigy turned functionary languishing at NASA’s “colored” computing department in Hampton, Virginia – a literal room of humans performing computation, soon to be presumably outmoded by the IBM machines being installed down the hall.

Dorothy Vaughan (Octavia Spencer) has assumed a supervisor’s responsibility for months without commensurate title, pay or respect from her “politely” prejudiced white superior (Kirsten Dunst).

Mary Jackson (Janelle Monáe) possesses an engineer’s inquisitive mind but bristles at challenging the myopic milieu that would prevent her from pursuing such a career.

These colleagues are introduced in a deft opening scene during which their car breaks down en route to work and a white police officer arrives. Rather than standard-issue bigotry, director / co-screenwriter Theodore Melfi illustrates the everyday ways in which Katherine, Dorothy and Mary navigate the world – skillfully manipulating the cop’s rock-star fascination with their NASA work into deflective admiration to make him feel useful even as they solve their automotive problem themselves. This can only get them so far, though, and they ache to go further. “Just when we start to get ahead, they move the finish lines,” Mary says.

Katherine’s unexpected promotion to pitch in on Project Mercury pushes Dorothy and Mary toward their pursuits – the former teaching herself the Fortran computer language to forestall obsolescence and the latter seeking education necessary to become an engineer … even as it takes her before a judge.

Melfi and Allison Schroeder’s screenplay generously parcels out equal screen time and rooting interest, as well as how Katherine, Dorothy and Mary grow to encourage others without reducing them to ciphers. (Also unremarked upon but underscored: The idea that the better Dorothy gets at facilitating Fortran, the less utility there may be for women like Katherine.)

Spencer endows Dorothy with the grace and gumption of a woman who knows her stepping stones have held her weight for far too long. Already a powerhouse musical performer, Monáe delivers a mid-movie monologue of activism and actualization that, alongside 2016’s “Moonlight,” further establishes her as an effervescent actress on the rise.

Ostensibly the lead, Henson navigates a single-mom-finds-love-again subplot (alongside “Moonlight’s” Mahershala Ali) with a pro’s patience. Of far greater interest is her personification of Katherine rediscovering prodigal skills – in little touches like her writing the wrong number in a flurry of computation, then realizing and erasing – and excavating the confidence to confront her new colleagues’ silent, shameful racism.

Again, Melfi makes the right step by making Katherine’s eventual ally not a white savior, but simply a boss who sees oppression as occupational obstruction. It’s a hardship that Al Harrison (Kevin Costner), Space Task Group director, doesn’t support but nevertheless can’t see – tunnel-visioned as he is to winning the Space Race even as a prescriptive knock on his program is that it’s a taxpayer boondoggle.

When Al can’t find Katherine (which is often), he assumes she’s shirking responsibilities. Instead, she’s running cross-campus – in heels – to colored bathrooms. Melfi gets much mileage, comic and sober, out of Katherine’s skittering (note how the flat-footed white guy who runs with her at one point is slower than her), and just when you hit your boiling point with it, so does Al. Again finding the usual effortless character-actor groove he has hit of late, Costner renders Harrison a strong, but besieged, leader who finds, in Katherine, a confidant for his own crises of conviction and confidence.

“Hidden Figures” isn’t content to rest its laurels on calling out prejudice for the sole, simple reason that “it’s wrong,” but for the ways in which it represents willfully ignorant blindness to the bigger picture of human potential and societal accomplishment. By understanding the hard-fought ways in which cultural perseverance factors into equations larger than any one of us, “Hidden Figures” earns its inspirational bona fides.