Inherent Vice

Inherent vice is a hidden defect in an object that, of itself, causes the object’s deterioration, damage or destruction — rendering the object an unacceptable risk to insurers or carriers. If the defect is invisible and insurers or carriers are unaware of it, neither is liable for claims that arise solely from inherent vice.

Underneath that actuarial language, there’s an emotional ache that defines “Inherent Vice” as a film. How liable can we be for temptations whose triggers we can’t possibly predict and to which all of us are secretly susceptible? Is corruptibility not an inherent, corrosive defect in love, freedom, friendship or respect — rendering loyalty not just for sale but on sale at an attractively low price? How does it feel to watch this defect erode the life we prefer to lead and the people with whom we want to share it?

Ultimately, “Inherent Vice” is a lament for losing your way in life, love and, in a sense, 1970s America. It’s not entirely a bummer, but it sure is a stronger strain than expected from what was advertised as a spiritual prequel to “The Big Lebowski” — a bumbling detective story in which the big sleep is what a gumshoe enjoys after a hearty bong rip.

Is it another era-specific treatise from writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson on how progress swallows people whole a la “There Will Be Blood” or “The Master”? Yes. Will you occasionally sense Anderson sweating as he condenses a byzantine book into a 148-minute frame? Absolutely. But it’s also freewheeling, breezy and funny in ways we’ve rarely seen Anderson attempt — an unexpectedly delightful detour not unlike his “Punch-Drunk Love,” able to maintain thematic weight while easing back on the intensity a bit.

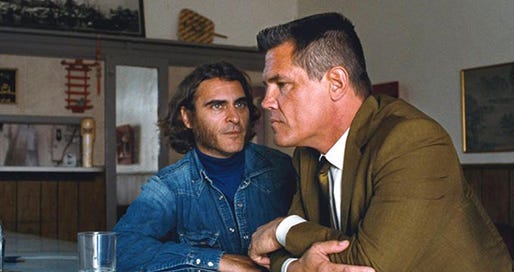

“Vice” is the sort of movie in which Maya Rudolph quips a cunnilingus joke so wild it could be a 007 pun, bit players spout the best Nazi punch lines since “The Blues Brothers,” Josh Brolin figuratively fellates a frozen banana in an unbroken take, a crushed velvet-clad Martin Short convulses in coked-up comic spasms, and singularly intense leading man Joaquin Phoenix — who couldn't be more different than his stress-hunched Freddie Quell in "The Master" — mellows his harsh playing a pot-smoking PI. (The menu for, uh, “add-ons” at a massage parlor is also one of the most uproarious sight gags in recent memory, as is the muscle charged to carry a certain precious cargo in a climactic scene.)

And yet “Vice” applies the ephemeral nature of its protagonist’s perpetual high to how easily his ethos and era could slip away in the early 1970s — making it of a thematic piece, albeit more blissed-out, with how larger cosmic forces betrayed Daniel Plainview or Freddie Quell.

Doc Sportello (Phoenix) is a brother shamus to the Dude, sure, but he’s more of a conscientious do-gooder. He considers himself at the frontline of having freedom to harmlessly fool around and find yourself — content to laze on his couch in a kush haze, but he’s cool if you crash that party, too. That’s what happens when old flame Shasta (Katherine Waterson) saunters back into his life, soliciting his services. It seems Mickey Wolfmann (Eric Roberts), Shasta’s real-estate entrepreneur sugar daddy, has disappeared, perhaps in a scheme by Mickey’s wife and her own boy toy to have Mickey declared insane and locked in an asylum.

Doc takes the case, which grows increasingly convoluted the more he digs. It mashes up actual “dirty tricks”-presaging sociopolitics with detective-movie tropes —Black Panthers, Aryan Brotherhood members, an Asian drug cartel, nose-picking Feds, Vegas bigwigs, an old missing-persons case of Doc’s, COINTELPRO informants, mob assassins, and — most imposingly — Lt. Det. Christian F. “Bigfoot” Bjornsen (Brolin), a buzz-cut LAPD brute and would-be actor with whom Doc shares a very tentative détente. (This doesn’t even hint at how Owen Wilson, Reese Witherspoon, Benicio Del Toro, and Jena Malone factor in.) And when Shasta disappears, it dredges up Doc’s wistful memories of their lost love.

As you can tell, Anderson’s adaptation includes nearly all the embers of Thomas Pynchon’s elaborately plotted novel. Just know that some of them burn out like roach clips at Doc’s feet. Some of the mysteries intersect and resolve — akin to “Chinatown,” with land swapped for water — but most crest and recede rather than coalesce into a clearly delineated conspiracy. It’s more about the idea of upstarts and stalwarts clashing, violently, against each other than it is piecing together who is nefariously aligned with whom. Knowing this, a second viewing could only help one lock into the movie’s mood — that of a B-side-filling, fuzzed-out groove that lulls at times but shifts its style just enough to hold your attention.

Part of that is in the vibrant verisimilitude exuded by Robert Elswit’s cinematography. Some of it is courtesy of Jonny Greenwood’s kooky score. Most of it derives from smartly nuanced performances across the board. Brolin plays his churlish lumbering for maximum laughs, but Bigfoot has dreams, too, and Anderson explores the toll they take on him. As an estimably professional prosecutor for whom Doc is a sexual release from the straight-and-narrow, Witherspoon embodies the cross-cultural curiosity as the ’60s morphed into the ’70s.

With a handful of “unabridged hippie monologues,” it seems “Vice” is tailor-made for Wilson’s babbling whisper, but he also captures the fear of a man who, in playing several sides against the middle, may have lost sight of his true beliefs. Only Del Toro (as a slightly less imbalanced lawyer than in “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas”) and Short are there for pure side-man comic pleasure, and neither disappoints.

That leaves Phoenix and Waterston, in whose on-off chemistry “Vice” finds its most sneakily moving passages. Doc is a lovable, loosey-goosey hero wishing to do right by people who deserve as much – an astute observer of human nature, good and bad. But Phoenix is cautious to not let Doc become a cartoon, evidenced by his concern when learning Shasta may be dead. She ultimately resurfaces in one of 2014’s most unexpectedly treacherous scenes — a one-take mini-masterpiece of manipulation, titillation, provocation and, eventually, capitulation. This moment’s sense of moral rot feels all the more revolting alongside an earlier, sweetly reminiscent flashback of happier days for Doc and Shasta. In both moments, Waterston’s is a luminous, star-making performance.

“As long as American life is something to be escaped from, there would always be a long list of new customers.” So goes the “vertical integration” business motto for a drug cartel toiling at the edges of “Vice.” It’s also the M.O. for every one of Anderson’s protagonists, all of them longing for an exodus to something different — prosperity, virility, respect, love. For Doc, it is a day when, as Jim Morrison once said, “everything was simpler and more confused.” His perhaps-futile pursuit yields a witty, wise and ambitious film just shy of Morrison’s stoned immaculate ideal, but awfully, and entertainingly, close.