Jobs

“Jobs” opens by reinserting magic into an everyday item — the iPod. As Apple Inc. co-founder Steve Jobs (Ashton Kutcher) introduces the music-playing device, his eyes twinkle with excitement. “This is a thousand songs in your pocket. It’s a tool for the heart,” he says. Here, Jobs embodies the film’s goal, reminding people of the childlike wonder with which they should view all the technology they take for granted.

As we later find out, Jobs wasn’t always such a sweet, enchanting entrepreneur. Before he founded Apple Computer, he was a pompous, freewheeling kook (not unlike Kutcher’s character in “That’70s Show”). The beginning of the film finds him wandering barefoot around Reed College after dropping out, occasionally sitting in on classes (including one on computers in which he is ironically anxious and bored).

He then takes a sharp, jarring turn, dropping a bit of his hippie-dippie attitude and showing fierce determination and superiority as a technician at Atari, Inc. There, he persuades friend Steve Wozniak (Josh Gad) to help him create a circuit board for the arcade game “Breakout.” Jobs’ enthusiasm and Wozniak’s technical knowledge lead to the foundation of Apple Computer in 1976.

From there, the film turns into a softer version of “The Social Network.” Like that film’s lead character, Facebook co-founder Mark Zuckerberg, Jobs ironically alienates himself from friends and colleagues in the process of building technology to bring people together.

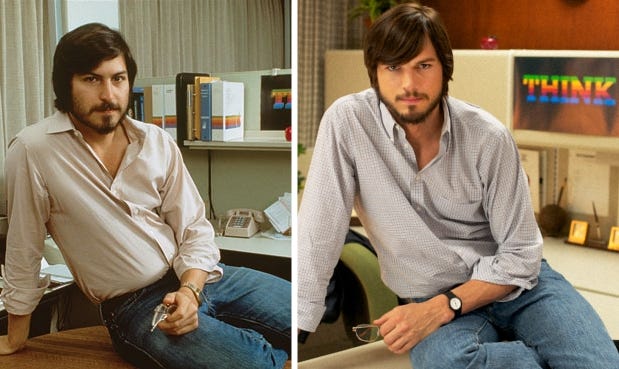

Kutcher delivers an interesting, nuanced performance, portraying Jobs as a bully but a fragile, vulnerable one, walking with a shuffled limp and whispering when angry. Like the film itself, his performance isn’t exactly towering, but it’s quite effective (and better than most people are expecting out of the usually goofy actor).

Gad is engaging as Wozniak, Jobs’ Jiminy Cricket. His tearful reminders of their friendship effectively accentuate Jobs’ soft side.

Rather than exploring the global implications of their work, screenwriter Matt Whiteley focuses more on this story of two kids learning to find the fun and magic in what they do. The grand irony of Jobs’ story is that he took his early work too seriously and didn’t realize he was still a kid playing with toys.

Whiteley also fulfills genre expectations by delivering big, iconic biopic moments — ones director Joshua Michael Stern films creatively and with wonder. For example, during the scene in which Jobs introduces the iPod, Stern shows him from afar, as if standing back in awe but also bringing the legend down to a human level. At the same time, he visually romanticizes the now everyday appliances Jobs helped create.

“Jobs” is not a grand, overwhelmingly powerful biopic, but it’s a sweet, enchanting film. Some critics have complained that it’s an inappropriately modest look at a man who was anything but. However, Jobs was more humble than he appeared. Late in his career, you could tell the blue-jean-wearing innovator was humbled by the magical technology with which he worked. There was a twinkle in his eye when he talked about it. This film captures his inner light.