Reeling Backward: King Rat (1965)

A grim but contemplative POW drama that muses on friendship and power.

"King Rat" is very different from your typical prisoner of war movie. It's not about grand escape attempts or antagonism with captors; indeed, the Japanese do not even show up until more than 30 minutes in and only appear briefly a few more times.

Although its main character is a flimflam man who unofficially rules the camp through his scheming and black market deals — much like William Holden in "Stalag 17" 12 years earlier — it's not really about that, either. Rather, it's a deep and probing look at the relationship between two very different men and how the travails of imprisonment push them to form inseparable bonds ... or not.

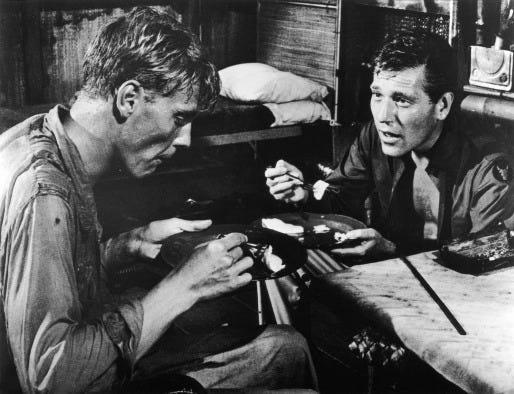

Corporal King (George Segal) is the ruler of the roost despite having one of the lowest ranks in the POW camp. He has a senior sergeant (Patrick O'Neal) as his personal lackey and gives impertinent answers to any query by an officer into his doings. Peter Marlowe (James Fox) is a terminally stiff-upper-lip British lieutenant who speaks the local dialect and is recruited by King as his interpreter and right-hand man.

At first, Marlowe is mortally insulted at King's offers to pay him for his services, insisting that's not how an English gentleman conducts himself. He helps King, but only out of a sense of friendship — though he does accept food, favors and, later, a little cash for his efforts. It's a delicious exploration of the differences between American and British culture, with the latter considering it humiliating to be seen striving too much.

King, meanwhile, is an enterprising soul. Indeed, capitalism seems to be the only thing residing in his nature. Everything to him is a contest, a game of oneupsmanship, a quest for profit.

The sale of a Rolex watch from an older British officer to one of the prison guards is instructive. The officer wants at least $1,200, knowing the watch is worth $3,500. King, acting as the middleman with Marlowe translating, talks the guard up from $400 to $2,200. But he tells the officer he only got $900, leaving him with $810 after King's 10% commission.

He then gives Marlowe his cut of $108, who doesn't want to take it, seeing it as a form of theft. But King fills him in. The guard will quickly resell the watch at a handsome profit, so he's happy. The watch was actually a fake, so the officer thought he was fooling both King and the guard, so he's happy. King duped them both and, being the smartest, took the lion's share of the stake. Reluctantly, Marlowe claims his share.

In this sense, "King Rat" is less about a con man than how that man relates to others in horrible circumstances.

The thing that really stood out for me about "King Rat" was how well writer/director Bryan Forbes, adapting the book by James Clavell, depicted the plight of the prisoners of the Changi prison camp near Singapore — mostly Brits and Aussies but a few Yanks, too. Either they exclusively hired actors and extras who were extraordinarily skinny, or the cast members were deprived of food to get just the right look.

Remember when Christian Bale famous starved himself for "The Machinist?" That's what most of the men we see are like — hollowed-out chests, sunken cheeks, toothpick arms and legs, stark rib cages. They're filthy, wear scraps of rags that used to be their uniforms, and have open sores or wounds.

Food is the number-one concern of their daily existence. Each man exists on a quarter-pound of rice per day, and dysentery and other disease are rampant.

Forbes makes the audience really feel their hunger. The only other movie I can think of that even comes close to projecting the same level of desperation is "Empire of the Sun." I think of the way all the animation goes out of the men's faces when a tasty morsel is shown in their presence. They practically turn into slavering dogs.

Speaking of dog: Perhaps the most pivotal scene in the movie is when King cooks a stew of dog meat for his closest chums, i.e., the people who work for him as various henchmen in his nefarious activities. The dog was the pet of one of their fellow prisoners, who was ordered to put it down when it killed one of the camp's valuable egg-laying hens. King "acquires" the carcass, but makes a point of not telling his guests it's dog until he's dishing out plates and they're literally slobbering at the smell.

This sets off a brief but not terribly enthusiastic debate about the ethics of eating a friend's beloved pet. The men are just looking for King to give them an excuse to indulge. They want him to convince them it's silly to waste the flesh when people (but not them) are starving: "Meat's meat," he says, with characteristic bluntness. They happily give in to his urging, and we get the sense the entire endeavor was about King testing their loyalty.

King's other significant protein enterprise is with rat, giving the book and film its name. They get their hands on a male and female rat and begin breeding them — with the unwitting help of a British officer and zoologist, whom they bribe to tell them all about the gestational periods and eating habits of vermin. Once their rat operation is big enough, they start selling off the meat, passing it off as mouse deer, a local delicacy enjoyed by the natives.

Two notable things about the rat meat business: They only sell to high-ranking officers, "majors and above." Even King has his principles, and feeding rat to his fellow enlisted men and junior officers just seems wrong (and risky). Also, they only cut off the hind legs at first, so the animals can continue living ... and making more little rats.

King differs from the other prisoners in keeping an appearance virtually unchanged from what you'd see of soldiers on their home base: crisp clean uniform, neatly trimmed and combed hair, fresh shave and manicure. Though Segal is as slim as an adolescent boy, he seems well-fed by the standards of the prison.

He struts around the camp like a peacock, drawing the stares and resentment of the half-dead, bedraggled creatures around him. He also provokes the ire of Grey (Tom Courtenay), the provost-marshal, aka chief law enforcement officer in the camp. A snide protector of the old world order, Grey is incensed at seeing an upstart American running roughshod over the rules — and enlisting British officers into his criminal web.

Justice is harsh and quick at Changi prison, and stealing food is seen as the worst possible crime. Early on, when one of the bags of rice comes up a couple of pounds short, the suspected (though never proven) culprit winds up face-first in a borehole. The prisoners use these to collect cockroaches and other bugs for protein — and also as a way to execute offenders in a dark and cruel manner.

The film concludes on a note that is simultaneously joyous and depressing. Marlowe's arm is injured and turns gangrenous, precipitating the need for an amputation. King sticks his neck way out to obtain the medicine necessary to save his life and the arm. Marlowe returns the gift with his unwavering loyalty.

But one day out of the blue, the Japanese commander announces that his country has surrendered, and the war is over. Soon after, a lone British soldier (Richard Dawson!) walks up and disarms the guards, officially ending the prisoners' captivity.

After a period of shock, the POWs go into a wild jubilation at the end of the war, but King retreats away from his criminal activities and his friendship with Marlowe. He knows the real world is about to reassert itself, and he'll go back to being a lowly corporal on the make. He abruptly snubs his British mate, calling him "sir" like it's a vile insult.

As he rides away from the camp with the other American soldiers, I think King really did feel a sense of affection for Marlowe. But he's also a hardcore pragmatist, and he knows that clinging to a false sense of equivalency will only lead to disappointment.

This is a strange and beautiful film — it earned Oscar nominations for black-and-white cinematography and art direction/set decoration — and a coldly compelling one. Its harsh and authentic depiction of POW life, and its total lack of sentimentality in its main character, are unique among other World War II movies.

"King Rat" hasn't maintained much of a reputation as the years have raced on. But I deem it a forgotten minor masterpiece.