Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time

A moving and very atypical biographical that's just as much about the legendary Hoosier author as his enduring friendship with the filmmaker.

“My books are a joke, really a mosaic of jokes, about very serious things.”

Kurt Vonnegut may have been the funniest man who ever lived when it came to scary stuff.

He wrote about death and genocide and depression and alienation, and other things we tend to keep crammed in the darkest corner of our souls. But invariably he did it with a puckish sense of humor that made these acid topics not only palatable but urgently relatable.

He was the darkest brand of Hoosier, who took his Indianapolis-born and -bred sensibilities and applied them to the sum of humanity, making us take a hard look at who we really are rather than how we would like to see ourselves. But always, always with that impish spark of sardonicism.

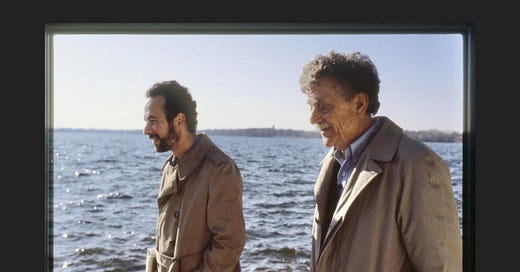

The new documentary, “Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time,” is at once a rich and satisfying look at the author’s life and work, and something else. It is also a movie about the making of this movie, and the friendship that grew up between Vonnegut and writer/director Robert Weide over the decades it took to come to screens.

Weide reached out to Vonnegut in the early 1980s as a young filmmaker, proposing the idea of a documentary about him. Vonnegut had seen and liked the movie Weide made about the Marx Brothers, and agreed. They began shooting, and then life invaded, and then they did some more shooting, and more life, until they had become fast friends and the film was just this thing in the background of their relationship.

So it’s as much a story about the making of a story — which is perhaps appropriate, since Vonnegut’s books were a web of autobiography and annotation, in which stand-ins for the writer or Vonnegut himself would make appearances, commenting upon the writing of the book as it was going along.

So we get the usual interviews with friends and scholars, archival footage and so forth. But also Weide himself appearing as a character making the movie, offering his own reminisces and thoughts. We hear phone messages Vonnegut for him left over the years, faxes he sent with thoughts and doodles, and behind-the-scenes footage such as the one where we see the writer pointing off into the stars from the dock in Lake Maxinkuckee, Ind., where he first invented the planet of Tralfamadore, and then them cracking up between takes.

The end product — written by Weide and co-directed by him along with Don Argott — is a very Vonnegut creature indeed.

I learned a lot of biographical context about Vonnegut from the documentary that I didn’t know before, the places he went and the important people in his life and how they affected him. He began his postwar career doing public relations for General Electric, and set himself a goal of having five magazine stories published before he would quit his job.

This sustained his family for awhile until, as friend and fellow Hoosier writer Dan Wakefield relates, “Television came and my cash cows all died.”

He struggled for the next 15 years, publishing books that didn’t make very much money. When his beloved sister, Allie, died just two days after becoming a widow herself, Kurt and his wife brought their four boys into their own household in quiet Barnstable in Cape Cod, transforming the house into a raucous center of frivolity and midemeanors, with the police making routine visits.

We see him visiting his hometown Indianapolis stomping grounds, placing his hand in the handprints left in the entryway cement of the expansive home that his father, a noted architect, designed himself. The Great Depression hit them hard, and they had to leave the place for lesser accommodations when Kurt was 10. When he was still a teenager, his mother committed suicide on Mother’s Day.

Of course, the most famous event in Vonnegut’s life was his presence as a prisoner of war at the firebombing of Dresden, which formed the basis of his most famous work, “Slaughterhouse-Five.” In one of the film’s many astonishing revelations, we hear from his daughters, Edie and Nanny, that they only learned about his wartime experiences when the book was published.

This event, in 1969, turned him overnight from a struggling writer who had to open a Saab dealership on the side to make ends meet into a literary celebrity — what Mark Twain was to the 19th century, Vonnegut was to the 20th.

We also see first-hand how Vonnegut, who had been steadfastly supported by his wife, Jane, for 20 years abandoned her for a younger woman. Vonnegut could pillory human foibles like celebrity better than anyone — but was not immune to our common vices.

The portrait we see in the interview portions is much the same as the public figure most of us know from his television appearances and public speeches: erudite but down to earth, a man who loved to laugh and make others do so, and quietly slip a bit of profound philosophy or nugget of wisdom in here and there.

During a visit to Shortridge High School, his alma mater, he displays the signature Vonnegut laugh: an open-mouth cackle that would eventually force him to stoop over at the waist, as if weighed down by too many funny thoughts.

He was a man of immense contradiction who would dismiss his horrific Dresden memories as no more important to his psyche than the dogs he played with as a boy, calling it “the great adventure of my life.” But those closest to him knew he was bluffing.

Over the years Weide collected enough material for 10 documentaries, even without reluctantly inserting himself into the story. But with Vonnegut gone 14 years now, the filmmaker — best known these days for his work on the “Curb Your Enthusiasm” show — decided now was the time to finally finish the project they’d embarked upon together so long ago.

Some personal events in his own life also spurred him, as you’ll see.

Since “Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time” is as much about the importance of extended families and laughter as the man himself, let me share my own little Vonnegut story.

In early 2007 I was excited for the chance to meet Vonnegut in person. He was set to return to his hometown to receive a major award (I forget what now), and I was to interview him for an exclusive story and present him at the ceremony.

Alas, he suffered a head injury and passed away before this unique opportunity could be consummated. This disappointment compounded with others at a difficult time in my life.

I’d joined The Indianapolis Star two years earlier as the entertainment editor, as close to a dream job as I could conceive, only to see the features department gradually decimated. Partly that was due to seismic shifts in the news industry, but also a profound lack of support from the paper’s editorial leadership, which made no effort to conceal its indifference to “soft news.” Their effrontery would extend to nominating sports and business stories for awards in the features categories.

Moved from editor to reporter, a role I’d deliberately left years earlier, I was wallowing in self-pity and resentment when the Vonnegut assignment came down the pike to restore my zeal. Beyond the immensely cool nature of the gig itself, I immediately hatched plans for the ultimate in-joke: a photograph of me with the legendary author holding our thumbs and forefingers in a circle.

If you don’t know or recall the Circle Game: you make the circle somewhere on your body and draw a friend’s attention to it, and if they look at it they get a punch in the shoulder. Yes, it’s juvenile — that’s the point. Friends played it through our teen and college times, and now as adults separated by long years and wide miles would exchange photographs of each other laying down circles to accrue points until our next meeting.

My friend Ben had moved out to Los Angeles to break into the movie business and started enlisting colleagues and celebrities into the game to spice things up. My plan was to do this with Vonnegut and send it to Ben, possibly his biggest in a veritable multitude of fans, to decisively win the game once and for all — the ultimate closing of the circle, so to speak.

It didn’t work out, Ben — but I hope you’ll appreciate the best joke that never was. I think Kurt Vonnegut, the merry imp who saw the worst of humanity and turned it into something bright and brilliant, would have approved.