Maria by Callas

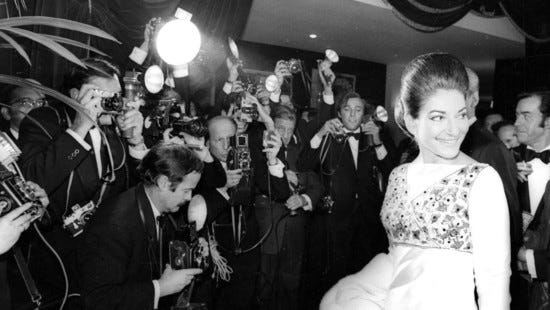

Maria Callas may have been the most photographed and filmed woman of her day, or any. It’s difficult for a normal person to think what it’s like to have almost your every daily movement tracked and recorded for posterity, often to be consumed by a public with an insatiable appetite for it. I think most of us would wilt in such a glare.

Luckily, one benefit of such a life lived is that it provides an abundance of material to document it, which is why “Maria by Callas” is an atypical and often compelling documentary film.

Rather than have a bunch of people talking about the opera diva’s legacy as an artist, director Tom Volf tells Callas’ tale in exactly her own words. The two-hour movie consists entirely of interviews with her, footage of her performances or public appearances, and deeply personal letters to friends read by (speaking voice) sound-alike Joyce DiDonato.

I confess I am not an opera aficionado; I don’t care for the way it bends the human voice into unnatural reverberations, and as a storytelling vehicle it feels very static and contrived. One of its chief obstacles as a popular art is that you’re looked down upon for not liking it.

But “Maria by Callas” focuses more on the woman than the artist. This is suggested by the title, as well as one of the earliest interviews shown, in which she talks about the dichotomy of living as the singer, Callas, and as a simple, shy woman, Maria. Savaged in the press for her tempestuous relationship with composers and maestros, as well as her often chaotic love life, Callas was loved and hated on an immense international scale.

She comes across in the film as self-involved, extremely intelligent, confident in her professional choices and retiring in her personal life. Decades before women were instructed they could “have it all,” she talks with open regret about the impossibility of having both a family, which she regarded as a woman’s highest calling, and enjoying the kind of career she did.

The documentary tracks her early life, born and raised in Brooklyn to Greek immigrants until they decided to move back to their homeland when she was a teenager, and being pressed into a musical career by her mother at age 13.

Curiously, the film offers nothing about her courtship and wedding to the much-older Giovanni Battista Meneghini, who she says traded on her celebrity. There is quite a bit, though, about her long-running romance with Greek tycoon Aristotle Onassis, which began as a friendship, then turned into an affair, then bounced back and forth between for the rest of their lives.

She was taken aback when Onassis suddenly married Jackie Kennedy in 1968 --- something Callas says she learned about by reading the newspapers. One letter written to him shortly before the betrayal is heartbreaking in the almost pathetic way she offers herself to him.

There are also several long performances from various parts of her career, which Volf feels compelled to relate in their entirety. I couldn’t tell you how wonderful a singer Callas was, though some dub her the greatest songstress of the 20th century, while others have called her sound “ugly” and “arid.”

I was more interested in her acting than her singing. While performing, Callas often clutched her hands to her chest, almost as if trying to protect herself while forcing the air out of her lungs. With her large, expressive eyes, bold protruding nose and wide mouth, Callas was not a classical beauty. But her presentation, like her voice, was so arresting because she did not seem to resemble any other person.

Maria Callas was, in a word, unique. While this documentary skims over some portions of her life and career that I would’ve found interesting -- such as how her dramatic early weight loss may have contributed to her vocal decline -- it’s still a fascinating film. The art may not inspire me, but this portrait of the artist does.