Melancholia

There are certain things you have to come into with a Lars von Trier film. When looking at some of his major films — including “Breaking the Waves," "Dancer in the Dark," "Dogville" and his laugh riot “Antichrist”, it’s clear that his films will likely be draining and bleak, yet they're also completely fascinating and usually worth watching.

Because Kirsten Dunst plays the lead, “Melancholia” is getting a wider release than the rest of the films. That doesn’t mean this is more accessible. Reminiscent of the gorgeous yet demented begining of “Antichrist," "Melancholia" opens with utter madness. The world is ending in slow motion with loud orchestra music guiding its exquisite scenes.

Then it’s right back to stark realism. A week before the planet will be destroyed, Dunst’s Justine is late to be married to Michael (“True Blood's" Alexander Skarsgard). She is full of smiles when she’s around him, but that all seems to fade when she finally gets to the church. Surrounded by too many trivial things like a bean contest and unsupportive attendees, Justine starts to snap.

Snapping doesn’t include freaking out or, as is von Trier's wont, self-mutilation (Dunst dodged that bullet). Instead, she stops caring. She cuts herself off from her family and refuses to take part in insincere events. Yet in the minds of the movie, she’s the sanest of them all. Why should people pretend to tolerate rude speeches or empty formal dinners?

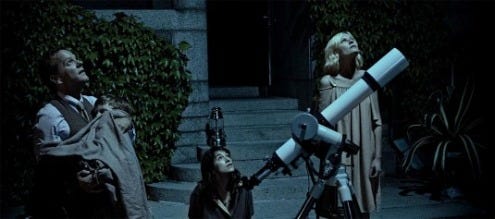

The stakes rise when a new planet is discovered hidden behind the sun and it seems to be heading right towards Earth. While Justine’s sister, Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg), is secretly concerned about the possibility of the world's end, Claire's brother-in-law, John (Kiefer Sutherland), reacts with overall denial of their impending doom.

On one hand, “Melancholia's" take on society never expressing its true emotions, even when those emotions clash with the culture, is fascinating. When it takes the step forward and suggests that love, marriage and most emotional relationships are equally frivolous, it isn’t as convincing.

Overall, there is odd beauty in all of the disaster. Dunst and Gainsbourg are brilliant together as sisters failing to understand their lives. Their pain and sympathy is what drives the film into such a compelling drama. As he’s evolved, von Trier has been able to use his Dogme filmmaking and mix it with high style into an effective new blend of storytelling. Even though this isn’t as complex as some of his other efforts, this crazy Dane continues to captivate.