Memoir of a Snail

Adam Elliot's highly personal "Clayography" stop-motion film is certainly not for kiddies, but its exploration of melancholy themes and tragic events makes for morbidly engaging cinema.

“Memoir of a Snail” is stop-motion animation for depressed people. That’s praise, not an insult.

Personally, I appreciate the use of animation to explore complex issues and even adult-themed material. “Snail” is rated R and very much not intended for kiddies, despite the morbidly fun aesthetic and art form, which people tend to automatically assume is for family-friendly fare.

It’s the brainchild of Australian animator Adam Elliot, who’s a paragon of independent, highly personal filmmaking. He won an Oscar for his 2003 short “Harvie Krumpet” and has only made one other feature, and reportedly worked on “Snail” for eight years. He refers to his style as “Clayography,” in that he employs old-school clay figures for his stop-motion animation, and all his stories are in some way autobiographical.

The movie is filled with wry humor but also plenty of tragedy and human degradation. It begins with a death — and not a typically pleasant cinematic one. The woman, Pinky (voice of Jacki Weaver), an elderly best friend to the main character, croaks out her last breath in a strangled wheeze of pain and fear, her face etched with years of physical and mental decay.

Let’s put it this way: I think a young Tim Burton, known for his fascination with the macabre, might have watched this film and thought, “Lighten up, dude.”

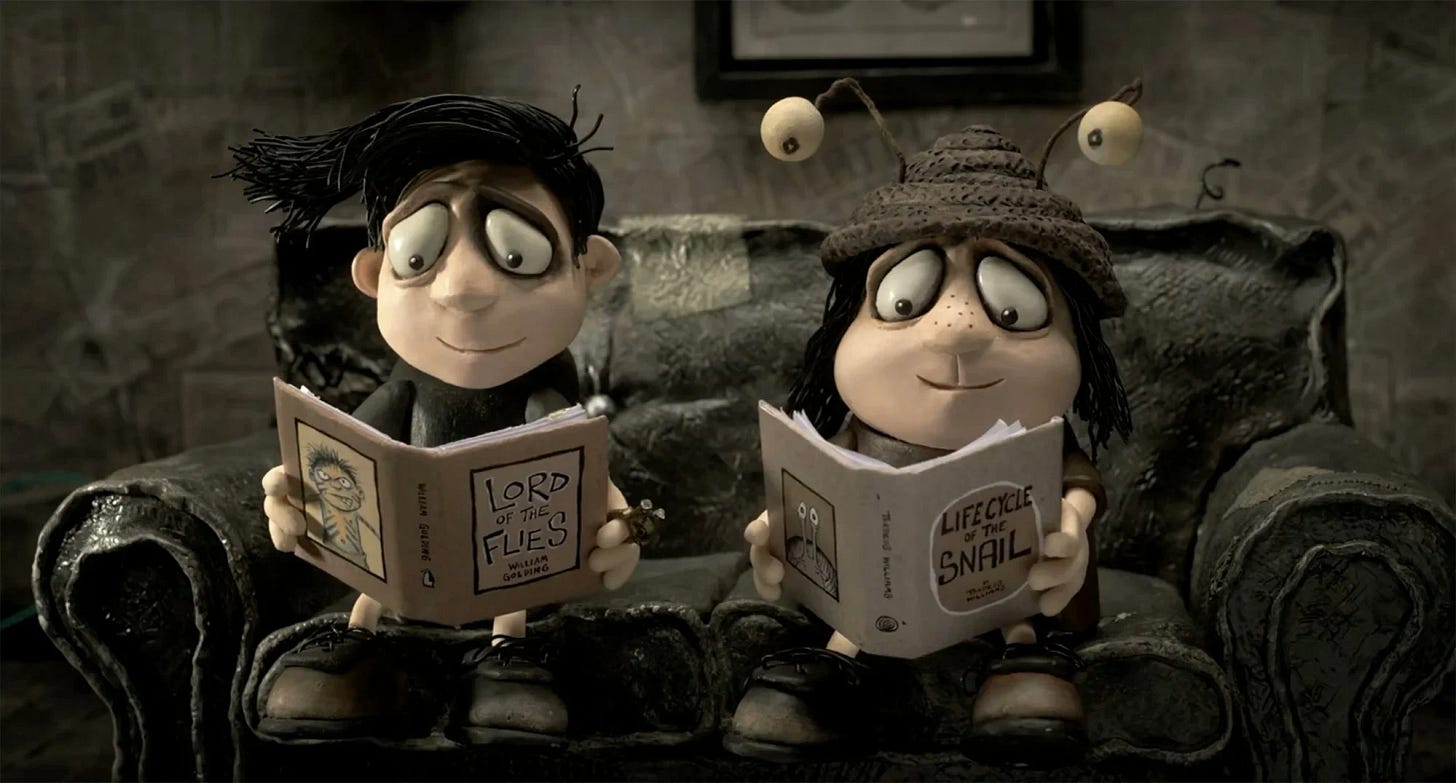

It’s the story of Grace Pudel (Sarah Snook), who grows up in harsh conditions but with a measure of happiness, and her life grows gradually danker and more challenging as the years go on. Chief among her woes is the separation from her twin brother, Gilbert (Kodi Smit-McPhee), when they are adopted by separate foster families on opposite sides of Australia.

Wearing an omnipresent slate-gray frock and a knitted hat with simulated eyeball stalks of a snail, Grace is under-educated, under-employed and most especially unappreciated. Snook narrates the story in the more or less present, after the passing of Pinky, a live-wire hippie who lived life to extremes that seem as fantastical mythology to Grace, who’s perpetually poor and stuck as a homebody.

Part of this life came from a sense of fear and lack of opportunities, but also by choice, Grace admits: “I always liked feeling caged in, snug and protected.”

Fascinated from an early age by snails, she has lived a life in a shell of her own making. She collects every kind of piece of art or knickknack with snails on it she can, simultaneously lamenting that she never has enough money to buy a plane ticket to visit Gilbert.

Perhaps the film’s most moving bit of tragicomedy is the flashback to her childhood with a father, Percy (Dominique Pinon) a French street magician (a nod to Elliot’s own papa) who became disabled after getting hit by a drunk driver. Their mother having died in childbirth, Gilbert and Grace take care of their dad without complaint, who mostly sleeps and drinks, occasionally reviving enough to take them on their favorite rickety roller-coaster.

His own death is the polar opposite of Pinky’s, abrupt and almost peaceful, yet seemingly more disturbing for it.

Grace is adopted by a pair of swingers — the key party kind, not the playground type — who mostly ignore her and eventually skip out entirely for a life of Swedish hedonism, leaving the house in Canberra to her. I have to say, Elliot’s claymation depiction of nudity, with heroically dangling “wobbly bits,” is just hilarious and human.

Gilbert gets the shorter end of the stick, made to work on an apple orchard by a clan of religious zealots, the kind who speak in tongues and tape magnets to their skin and practice hypocrisy as a companion enterprise to the farm. A born fire bug, Gilbert smells of burnt matches, Grace says, is a kindly soul but ready to fight back when faced with bullying.

A bit of joy enters Grace’s drab existence in the form of a new neighbor, Ken (Tony Armstrong) a somewhat older man with a thing for lawn care. He accepts Grace’s snail fixation without complaint, dotes on her and feeds her little sausages, and they soon marry. But the darkness always pulling on Grace’s leg reasserts its grip.

The animation style is intentionally bleak and drab, almost black-and-white, and does not try to look realistic but revels in its outlandish proportions and depiction, such as hair looking like strings of chaotic wire. You can see the knife cuts in the clay figures, such as the wrinkles on older faces. It’s got a sort of raw purity to it.

The music by Elena Kats-Chernin is captivating and, of course, quite dour.

Have I made “Memoir of a Snail” seem too depressing to see? It’s not. You’ll just have to go in with full knowledge of the experience you’ll be getting: a little funny, a little sad, with its own distinct form of beauty.