No Sleep October: John Carpenter's "Apocalypse Trilogy"

This No Sleep October, Friday afternoons will focus on a series or thematic sequence rather than a single movie.

I've been curious about John Carpenter's “Apocalypse Trilogy” for some time. The trilogy is a thematic trilogy released over 15 years: “The Thing" (1982), “Prince of Darkness” (1988) and “In the Mouth of Madness” (1995). I've been familiar with “The Thing” since high school. It was one of the few horror movies I was a fan of at the time. I showed it to all of my friends. I watched it frequently. I memorized portions of it. I adore it.

Could the other two live up to it? Yes.

The concept of the cosmic apocalypse has become mainstream, largely in Lovecraftian terms. It's generally watered down. Most of these stories / games / movies / comics / books are part of the "fantasy apocalypse" trend, where the “unknowable” and “unspeakable” Gods are perfectly knowable and describable.

Sure, the conclusions of the stories may still be pessimistic, but the actual end of the world is defined as a moment to test yourself. There's a distinct lack of nihilism. The Elder Gods concept is now nothing but another pantheon of marketable characters. In the “Apocalypse Trilogy,” Carpenter never really names his beasts. He never destroys the entire world on camera. His heroes are flawed, broken, ambiguous, lost in the mess at the end of all things. The horror at the heart of these three movies is not big monsters or wacky languages but the ultimate degradation of the human of body, spirit and mind to the point of complete and total annihilation. These are pageants of utter loss.

Each of the movies could not be more different, but through that trifecta of what makes a human being — the body, the spirit, and the mind — you can see just how well each of them depicts the idea of cosmic apocalypse.

The Body The Thing (1982)

While each entry in the “Apocalypse” trilogy features body horror, “The Thing” is the one to really focus on it. A team of scientists and military men working at remote Antarctic station Outpost 31 is haunted by an alien being that can absorb living beings and assume their form. To make matters worse, winter arrives and traps them in the station.

There is no hope of salvation; if the ice thaws and rescue arrives, the Thing might well make it to the mainland and end all life on Earth.

Alcoholic helicopter pilot MacReady (Kurt Russell), Childs (Keith David), the captain, Garry (Donald Moffat), and the other nine men at the station slowly fall into paranoia and delusion. None of them know which one is the Thing; neither does the audience. The Thing behaves like the person or animal it replicates. It's even possible that you don't know that you're a replicant.

Loss of the body is twofold in “The Thing.” Most obviously is the body-horror, well-renowned. When the Thing is threatened, it loses shape, becoming all sorts of bizarro monstrosities. There's quite a lot of gore, and a number of scenes that push the limit. (“This isn't scary,” my fiancée said. “This is just gross.”) And it is! It's certainly disgusting, but disgusting with a purpose. The Thing needs time to change form. When the surviving members of Outpost 31 begin to corner their foe, it eventually reverts into an amalgam of every beast it has become in the past. Its physical form loses coherency, defies the logic of anatomy. Visually, it is pure perversion.

The body-horror is definitive, but in the context of the three films of the trilogy, “The Thing” is the most focused on a single social group shattering in the face of unspeakable fear. It is the social body in microcosm. After the death of the first crewman, Garry (Donald Moffat), head of the station, woefully cries that there's no way his friend had become a Thing; he'd known him for years. What sets MacReady apart is his antisocial behavior, which proves to be a liability when he becomes the most prominent suspect.

The Soul “Prince of Darkness (1987)”

“Prince of Darkness” is a spiritual successor to “The Thing” in that it features a cosmic apocalypse, albeit of a different kind. It features plenty of bodily mutilation and visually scarring imagery, but it focuses much more on dissolution of the soul and the structures we put in place to define it.

The threat is more or less abstract, and its victory more nebulous.

Priest (Donald Pleasence) invites Harvard Professor Black (Victor Wong) and several physics students into the basement of a Los Angeles church, where an ancient papal secret is kept. They find a glass tube with swirling green liquid that transmits mysterious data. At first they believe it to be Satan; what they find is that it is ultimately so much worse. It is the Anti-God, an ancient monster of unimaginable strength. And it is no longer dormant.

The crew of scientists experiences an exquisitely creepy shared dream of the future, featuring a mysterious shadowed figure in a doorway, telling them to prevent a certain catastrophe. Sure enough, members of the team slowly fall prey to corruption. Some are killed outright while others are possessed by the Anti-God's dark magic, becoming servants. Unlike “The Thing,” where identity is questionable and nobody can be trusted, Anti-God's servants are dead-eyed and proud. They wear a mark of corruption on their arms. They are broken souls controlled by something beyond all reckoning.

Dread builds as the inverted crescent moon rises in the sunlit sky, as hordes of the homeless surround the church and yearn for their master, as Priest comes to realize that his life's work was built on a complete misunderstanding of the nature of God. There's a distinctly low-budget feel to “Prince of Darkness."

My favorite scenes in “Prince of Darkness” were not the various terrifying gore bits, but the conversations between Priest and Black where they hash out just how far astray the church led humanity. How our perception of a matter-based universe makes us assume God is one of matter, but that the implicit existence of anti-matter means a natural mirror would have to exist, and perhaps, perhaps the God mankind first encountered was from that side.

It is a complete crushing of the Soul.

Of the trilogy, “Prince of Darkness” scared me the least, but I loved it quite a bit. I enjoyed Carpenter's soundtrack the most of the three soundtracks. It is pitch-perfect. The subdued visuals were compelling. There's plenty of gore, but most of the film is told through images like the perverse cosmology and the labyrinth church. It feels distinctly tactile in a way gore sometimes doesn't.

Awesome.

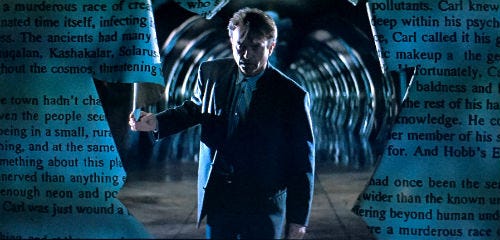

The Mind “In the Mouth of Madness (1995)”

In “In the Mouth of Madness,” the mind and its grasp on reality is broken completely. Writer Michael de Luca was directly inspired by H.P. Lovecraft and directly references the his work in the book. Hell, the title itself is a tribute to “At the Mountains of Madness,” a seminal Lovecraft story. “Madness” captures its titular emotion perfectly: Insurance investigator John Trent (Sam Neill) is sent on the trail of missing horror author Sutter Cane (Jürgen Prochnow). Crane is like Stephen King or Lovecraft, but more popular, more widely regarded. Fans can't put down his books. Some of them even seem to go mad. Trent soon finds himself trapped in the withering barrier between fiction and reality.

“Reality is just what we tell each other it is,” says Linda Styles (Julie Carmen), Cane editor, who accompanies Trent on his mission. The two soon find themselves in Hobbs End, a fictional New Hampshire town featured in many of Cane's books. When they finally find the elusive author it becomes clear that his story ideas don't come from his own imagination; that they may well come from a far greater, older, more terrifying power.

I was a fan of Stephen King growing up. I still think he's one of America's greatest storytellers. I would read Sutter Cane! In this movie, everybody is a reader of Sutter Cane. And if they don't read? They see the movies. And Sutter Cane's stories create and sustain reality for his readers. Isn't that what we're looking for, in our fiction? The idea is just as relevant as ever, in this, the year of the "dank meme" political action groups, identity built on consumer products and designer reality via social media. In some ways, the horror that Trent experiences when he travels to New Hampshire to find Cane is less terrifying than the reality we call home.

It isn't really subtext. One of the best scenes in the movie has Trent hiding in a confession booth, with Cane on the other side. Cane talks about how much more influential his writings are than religious belief. How nobody has “ever believed the Bible as much as they believe in me.” Maybe not. It's never a bad thing for fiction to lay bare the fact that the actual stories in the Bible are not what bind us, that the underlying social belonging is what feeds our need to believe in the stories we share and not the content of the stories themselves.

Unlike “Prince of Darkness,” “Madness” approaches the idea of old forces from beyond our reality in a more material way. We see them (or at least Trent believes he sees them); they are terrifying. They are, like Anti-God, monstrosities from the other side of the door. This depiction of physically real monsters contributes to the madness angle of the movie, just as the formless beast in “Darkness” contributes to the spiritual decay in that movie. Neither, however, goes so far as to put these monsters into the physical realm to wreck havoc, to destroy cities, to murder millions. They help convey the cosmic apocalypse. They are not, in and of themselves, that great end of all things.

Compared to the other two movies in the trilogy, “Madness” doubles down on the ambiguity. It's deliciously incoherent. Reportedly, the actors weren't quite sure what the story even was while filming. It's open to interpretation. As I see it, the relationship between Trent's breakdown is scary enough as it is, without the end of the world being a tactile result of his journey. Whether or not Cane actually controls reality with his pen (as the end of the movie suggests) is immaterial. It's a perfect, fun, frightening cinematic descent into madness.

I was impressed by the “Apocalypse Trilogy” as a whole. I think each of them are perfect encapsulations of what I look for in the cosmic horror genre, examples to be followed. Taken together, they highlight the central elements of how to make such a broad concept personal, relatable, utterly dreadful. Each movie features scenes of terror that sat in the forefront of my brain when awake in the middle of the night, but more importantly they were movies that I enjoyed thinking about for several days after watching.

Highly recommended.