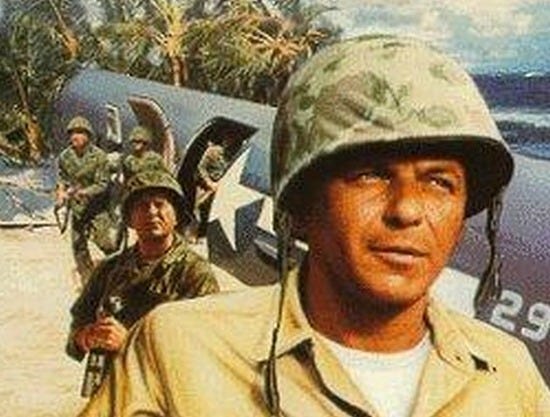

None But the Brave (1965)

I've made it something of a hobby horse in this space to touch on movies directed by well-known actors who made it their first and last effort behind the camera. These include the only films directed by the likes of Charles Laughton, Marlon Brando and Karl Malden. Now it's Frank Sinatra's turn and his 1965 anti-war movie, "None But the Brave."

It's a rather ham-handed picture — demonstrating that Sinatra's rightful place was in front of the camera or behind a microphone, not in the director's chair — but it's notable for several reasons.

The most obvious are that it was the first joint Japanese/American production, and it depicted World War II from more or less morally equivalent vantage points. Decades before Clint Eastwood's "Letters from Iwo Jima," a Japanese-centric companion piece to the American-leaning "Flags of Our Fathers," Sinatra's film melded the American and Japanese stories into one.

It's about two small forces of soldiers stranded together on a lonely island far away from the action. The war still plays out in a micro version, though, with an outbreak of humanism that holds the bloodshed at bay, at least for a time.

Written by John Twist and Katsuya Susaki, it's a quite pessimistic tale that essentially argues that men are doomed to repeat their mistakes by embracing violence rather than dialogue. We rigidly stay inside our respective silos, divided by nation, race, religion, etc., and fail to see the humanity in each other.

It's a noble sentiment, but one delivered without an ounce of subtlety or originality. As if the film's message weren't clear enough, the title card at the end hammers us square in the forehead: "Nobody ever wins."

(Which is, of course, an idiotic statement on its face. Ask the millions of descendants of Jews who survived the death camps if the Allies' victory was worthwhile or not.)

Sinatra gives himself a supporting role as the chief pharmacist mate aboard a cargo plane that is shot down over the island. The chief — no name is every given — is a combination of comic relief and needling voice of reason, who imbibes liberally of the large stock of whiskey among the medical supplies the plane was carrying. (Which all, apparently miraculously, survived a high-speed crash landing on the beach.)

The real protagonists are Captain Bourke (Clint Walker) on the American side, and Lt. Kuroki (Tatsuya Mihashi) for the Japanese. The latter narrates, as writings in a journal addressed to his bride, whom he married on the day he left for the war. Kuroki has a great deal of both humility and conceit about him, describing himself as a descendant of samurai warriors who loves life and the handiwork of mankind.

This is demonstrated in the early going as Kuroki chastises his hidebound sergeant, Tamura (Takeshi Katô), for working the men too hard in the harsh Pacific sun. They are building a boat to send a contingent to make contact with their command and replace destroyed "communicational" equipment. What they don't know is the American naval advance has pushed their tiny island far outside the reach of the Japanese Empire.

The sergeant grumbles, but obeys. Their force also includes a peasant fisherman and a Buddhist priest, both rotund and cheerful and competing for the distinction of worst soldier in the Japanese military. The men clearly respect and adore their lieutenant.

Would that it were so on the Yank side. Bourke spends the first half of the movie convincing the unruly Army soldiers to follow his lead, citing a fictitious piece of military code that any troops aboard his plane remain under his command until such time as they reach their destination. Bourke isn't power-hungry, but simply recognizes that their greenhorn second lieutenant, Blair (Tommy Sands), is likely to march into a Japanese ambush if he doesn't assert a more cautious hand.

A word on screen presence: Man, did Clint Walker have it. Though he's not a household name, Walker is a contender for the most impressive physical specimen ever to walk on a Hollywood sound stage. Fully 6½ feet tall, with a 48-inch chest and 32-inch waist, lantern jaw, jet black hair, Caribbean blue eyes and basso profundo voice, he was television's first Western star in "Cheyenne," which ran from 1955 to 1963. He literally looks like Superman come to life.

(In 1971 he was impaled through the heart by a ski pole in a freak accident and pronounced dead. But a doctor detected slight signs of life. Walker was revived, recovered and, at 88, is still with us today.)

His Bourke is a pragmatic man with his own woman troubles back home. He's supposedly seen a lot of action — odd for a cargo pilot — and organizes his men on the far side of the island so they can scout the enemy. Lt. Blair openly challenges his authority at every turn, backed up by pug-nosed Sgt. Bleeker (Brad Dexter), whom Bourke has to put in his place with personal fisticuffs. (Dexter, who often played the big bully, looks like a little twerp next to Walker.)

And then there's Tommy Sands' portrayal of the headstrong lieutenant.

... Tommy, Tommy, Tommy ...

This has to go down as one of the most ill-thought performances in Hollywood history. Employing an over-the-top Texas accent, Blair yelps and over-enunciates his words like a carnival barker hocking joy juice to the local rubes. He's not playing a "type," he's playing a caricature. Every time he appears onscreen, it's a distraction. It's like something out of a "Rocky & Bullwinkle" cartoon.

A more experienced director would've quickly put Sands in his place, or found another actor. Sinatra didn't do that, to the movie's detriment.

Sands — who, like Sinatra, got his start as a teenage pop music idol — saw his career go down the poop chute right around the time this movie was being made, reputedly with the help of Sinatra, who encouraged his showbiz pals not to hire him. Though this was most likely retaliation for Sands divorcing his daughter, Nancy. Perhaps the younger crooner saw the writing on the wall and decided to stink up his father-in-law's movie as preemptive revenge.

Anyway, things progress as you'd expect. After some initial skirmishes and deaths, including the boat being blown up, the respective commanders set up an exchange in which the chief — who's passed off as a doctor — amputates the gangrenous leg of a Japanese corporal in exchange for the Americans getting access to the only fresh spring on the island.

From there it's happy-happy time, with the men smiling and exchanging fish for cigarettes, with the barest of demarcations between the American and Japanese sides of the islands. Then Bourke fixes his busted radio and manages to arrange for a U.S. destroyer to pick them up, so all bets are off and the war's back on.

Why exactly? From a character/motivational standpoint, it makes little sense. Kuroki, having been established as the wisest man on the island, suddenly insists that it's his obligation to prevent the Americans from getting aboard that ship and becoming operational parts of the American war effort again. Bourke offers to accept their surrender and take them along, but Kuroki would rather lead his men to certain death in a useless gesture toward his sense of duty.

While it's not so that nobody ever wins in war, it is very much true that many people lose. Kuroki loses his personal war by remembering his patriotic one. Narratively, this war film loses by shoehorning conflict into places it doesn't fit.

Frank Sinatra's sole directorial effort isn't awful, but it's easily the weakest of those I've visited. Of course, I haven't written about Matthew Broderick's 1996 effort, "Infinity"...