Paper Lion (1968)

It's impossible to underestimate the power of expertise. Despite whatever natural gifts we may have, they only come after endless hours, days, weeks, months and years of practice to hone our skills. Whether it's writing a coherent paragraph or throwing a perfect spiral pass, only time and experience allow us to become truly superlative at our endeavors.

Many have heard of the "10,000-Hour Rule" posited by Malcolm Gladwell in his book, "Outliers." It states that it takes that much time practicing a specific task to become an expert in it. The most famous example is that the Beatles played thousands of gigs between 1961 and 1964 before they broke out big.

The point is that academic study is no substitute for practical hands-on experience.

It reminds me of a story I often relate to show the difference between being an expert and a dilettante. While my 1969 Mustang spent the better part of a year in the shop being restored, I arranged to help out with the work to keep the bill down. I spent many Friday afternoons and Saturday mornings scraping paint, working on the interior and other odd jobs. I probably got in the way of the real mechanics more than I actually contributed, but I enjoyed being part of the process and learning something about how cars are put together.

Near the end of the restoration, the boss instructed me to install the light fixture on the rear bumper that illuminates the license plate. (Even though technically he was working for me, part of our agreement was that while I was in his shop, I had to do what he said.) I had the plate with the wire sticking out of it detached from the bumper so I could put in a new bulb, and then it was just a matter of screwing it in. But I couldn't get the light to come on. I checked and rechecked the connection, tried a different bulb and spent probably 15 minutes futzing around with this light that I couldn't get to work.

Finally, I gave up and asked the boss to come look. He eyed the problem for about a second-and-a-half, then took the dangling plate and held it up so it touched the bumper. Immediately the light flickered on. He patiently explained that the metal fixture needed to be touching the bumper to close the electrical circuit.

Now, having been a halfway decent high school science student, I already knew this. But I'd never worked hands-on with something like this, so I couldn't grasp the simple nuts-and-bolts of how things worked. To the mechanic, who'd spent literally decades taking cars apart and putting them back together again, this was a no-brainer. But it stumped a non-expert.

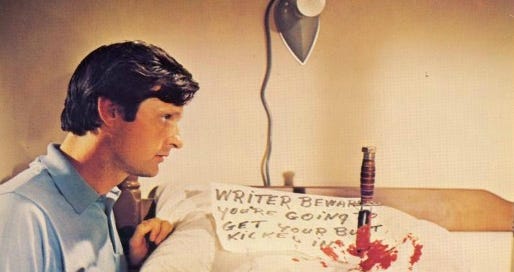

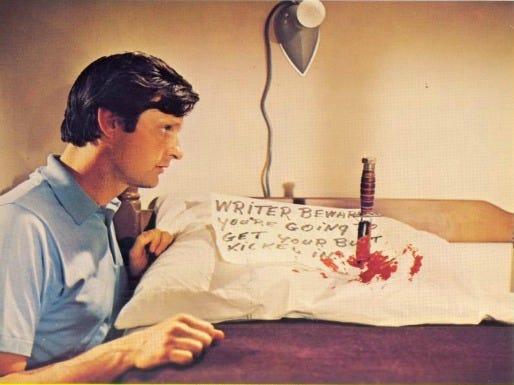

This is very much the unstated subject of George Plimpton's 1966 book "Paper Lion," which became a movie starring Alan Alda two years later. Plimpton had already written a book about pitching to major leaguers in the All-Star Game and gone a few rounds in the ring with a champion boxer for another piece. He was convinced by his editor at Sports Illustrated (David Doyle) to try to replicate the feat as a quarterback in the National Football League.

The basic idea was to see how an everyman athlete would fare against elite professionals. The answer, not surprisingly, is that he would get his rear end handed to them. This is exactly what happens to Plimpton, though the movie is more interesting for its behind-the-scenes portrait of NFL players just as the league was coming to dominate American sports.

Plimpton shows up at training camp for the Detroit Lions with only the coaching staff aware of the ruse. Plimpton, who was 36 years old at the time, claims to have been playing semi-pro ball for the Newfoundland Newfs. In reality, his only experience playing quarterback was in co-ed touch football games with friends in Central Park.

Still, the other players more or less accept him for what he seems to be: an over-the-hill rookie taking a final, unlikely shot at a roster spot in the NFL. They joke about his Harvard alma mater and spindly body — a weigh-in scene claims him as 175 pounds, though I'd guess Alda was actually about 20 pounds under that — but no one dismisses him out of hand.

Until, that is, Plimpton engages in his first real practice scrimmage and shows himself to be incapable of receiving the snap from the center. It's one of the typical little skills any serious football player acquires, knowing how to position the hands so the snapper knows you're there but doesn't break your fingers with the ball. Because Plimpton lacked that commonplace ability, the players immediately knew he was a charlatan.

This is probably the most interesting section of the movie, as Plimpton, having been revealed as an SI writer, struggles to fit in with the players and their unspoken code of honor. In an amazing bit of casting, not to mention logistics, all of the actual Lions players and coaches depict themselves, including Alex Karras, Joe Schmidt, Roger Brown, John Gordy, Mike Lucci and so on. Vince Lombardi and Frank Gifford even turn up.

A few of the performances are wooden — Schmidt speaks all of his dialogue as if from a cue card held just off-camera — but most of the players are completely naturalistic and believable.

At first, the players are offended that an amateur would be inserted amidst their ranks. One gives a speech about how, unlike boxing and baseball, football is a total team effort. Everyone has to know what everyone else on the field is doing. If they don't, error and injury usually occur. Having one inept man in the huddle can result in disaster.

Now, this palooka might have given up 70 I.Q. points to Plimpton. But in his native environment, he's the genius while the brilliant writer is the dimwit.

Director Alex March, a TV lifer who only directed one other feature film apart from this one, makes the bold choice of layering dialogue on top of itself, so the audience feels like it's really in the midst of a bunch of bantering guys. For the final sequence involving a preseason game against the St. Louis Rams, March apparently filmed a real game with the players miked up and used their extemporaneous mutterings to great effect.

Years later, Robert Altman would use this same technique in "Nashville" and other great films.

Of course, this being a Hollywood movie instead of a straight piece of journalism, things get changed around a bit. The most notable is that Plimpton never got into a real game with another team. NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle found out about his presence on the team in the middle of a preseason game and, at halftime, Schmidt was ordered not to put Plimpton into the game under any circumstances.

His fictional performance in that game actually matches one Plimpton related in his book during inter-team scrimmage, when he managed to lose yardage on five consecutive plays. Another scene invented for the movie shows him scoring a touchdown during practice, but he later learns it was a setup. But in the end, the coaching staff and players respect Plimpton for his efforts, taking his hits without complaint, and all sign the game ball for him.

Another major disparity with reality is the presence of Karras, then one of the most popular players in the NFL, as one of the top supporting players. In actuality, during the preseason Plimpton spent with the Lions, which was 1963, Karras was suspended from the league for gambling. He's still an amiable presence, part bruiser and part back-slapper, and it's no surprise that he would go on to a healthy television and film career after his term on the gridiron ended.

In addition, the movie shows Roger Brown being traded to the Rams, something that didn't happen until 1966. Schmidt also wasn't the coach during 1963.

Lauren Hutton made her film debut in "Paper Lion" as Kate, though it's never quite clear if she's supposed to be Plimpton's assistant, his lover or some combination of both. She's a vision of loveliness, of course, and draws a lot of attention from the other Lions.

"Paper Lion" isn't a particularly well-crafted movie. March's camera work is a bit confusing, especially during the football scenes. Alda is a feisty presence, though, and I enjoyed the way the film brutally shows what it's like on the wrong end of a quarterback sack.

3.5 Yaps