Reeling Backward: Gigi (1958)

A gorgeous and colorful Parisian romp, though the musical that won the 1958 Oscar for Best Picture hasn't aged particularly well, especially in its gender dynamics.

Here’s how dim I am: I watched the entirety of “Gigi,” the Best Picture Oscar winner for 1958, without realizing it was about a young girl training to be a courtesan.

Set in 1900, the novella by author Colette is about the titular teenage character who is being groomed by her grandmother as a professional mistress — several steps up from a streetwalking prostitute, to be sure, but still someone who makes their living from sex.

In turn of the (last) century Paris, it was commonplace for well-to-do men (married or not) to have a financial relationship with a courtesan, essentially giving them sole rights to her favors in exchange for a place to live and a stipend. This arrangement could last for months or even years. In the end of Colette’s romantic fable, Gigi and her intended benefactor, sugar tycoon Gaston, fall in love and marry instead.

The book was adapted into a 1951 Broadway play written by Anita Loos, starring a then-unknown Audrey Hepburn as Gigi. Hollywood megaproducer Arthur Freed had the idea to turn it into a musical, and recruited lyricist Alan Jay Lerner to write the screenplay, who later brought in his frequent collaborator Frederick Loewe to co-write the the songs and compose the musical score. Vincente Minnelli was tapped to direct.

They were extremely concerned about the prospects of bringing a story about an underage courtesan-in-training to the screen in the Hays Code era; Freed had also been grist for the Hollywood Blacklist and was understandably cautious.

I guess they were very successful in their obliqueness, as I was clueless. The movie only makes very vague references to ‘conducting business’ or ‘making an arrangement’ about whether Gigi would have a car and servants and such. I honestly thought they were talking about prenuptial agreements or dowries, or whatever the circa 1900 equivalent of those there were.

Hepburn was approached about reprising her role, but had become a very big star in the intervening years including “Roman Holiday,” “Funny Face,” “Sabrina” and “Love in the Afternoon,” and turned it down. There was also the issue of her lack of singing ability. (“Moon River” was specially written for her in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” to mask her lack of range and tone.)

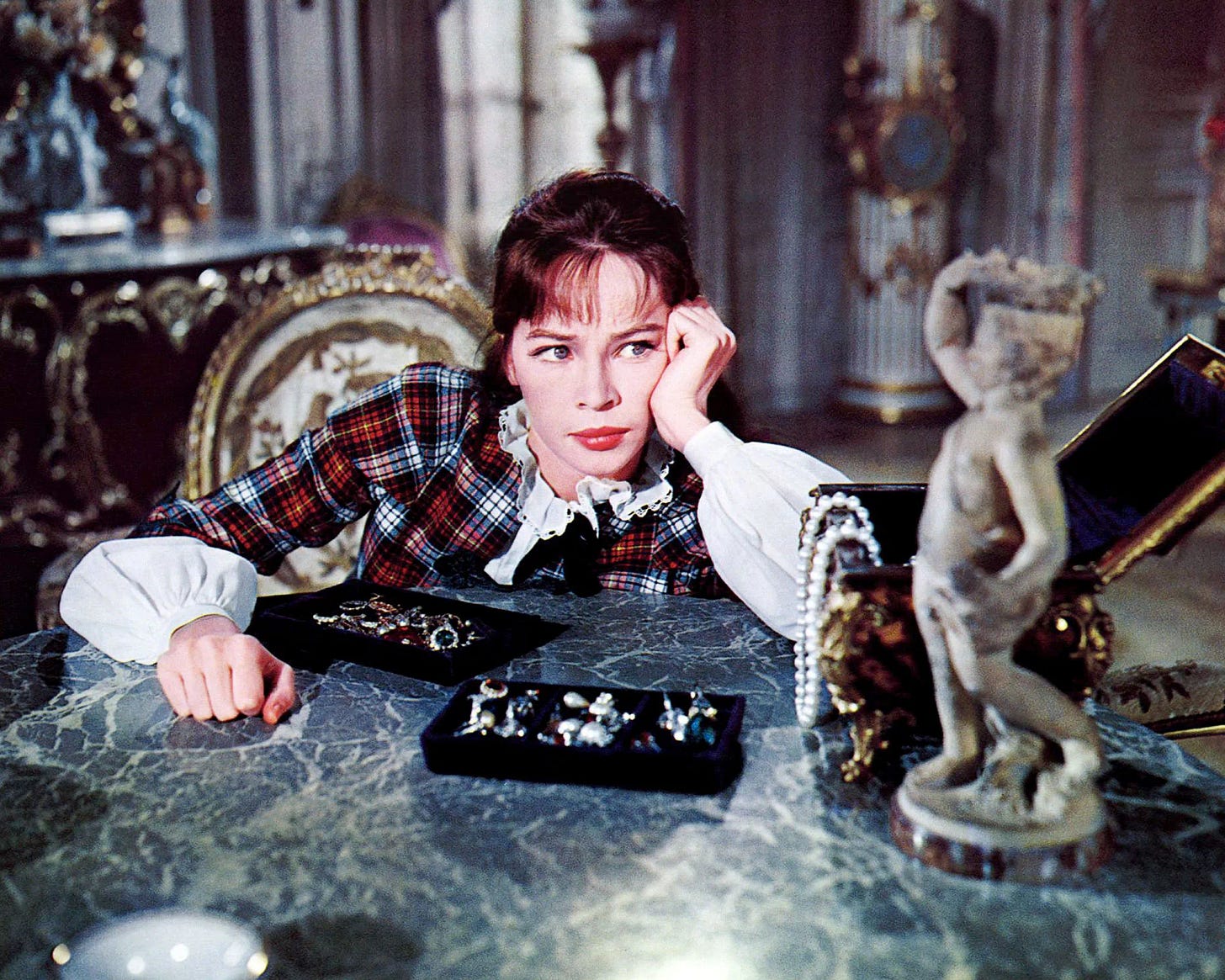

Leslie Caron, who had co-starred in “An American in Paris” for Freed and Minnelli, had played Gigi in a subsequent stage production and agreed to reprise the role for a musical version. She also had the benefit of being French. Though a more than able dancer, it turns out Caron couldn’t sing, either, so her voice was dubbed by Betty Wand, who also vocally stood in for Rita Morena in “West Side Story.”

For that matter, Louis Jourdan, who plays Gaston, isn’t much of a crooner himself, mostly sticking to the (in)famous “talk singing” method employed by everyone from James Cagney to Rex Harrison.

Really, the only professional singer in the main cast is Maurice Chevalier, whose part was written specifically for him and remains arguably his most iconic film role. He plays Gaston’s uncle and advisor in affairs of the heart, Honoré Lachaille, who also acts as something like the film’s narrator.

He takes an outsized role in the singing duties, featuring several solo pieces and one duet, compared to the tertiary importance of his character in the story. He does have a lovely warm tone and engaging, quintessentially French phrasing.

(Jerry Orbach would later do a spot-on impersonation of Chevalier as Lumiere in “Beauty and the Beast.”)

The most memorably is surely “Thank Heaven for Little Girls,” a song I grew up with without every associating it with the movie. Once you see it in the film, though, it does take on something of an icky note. Honoré is singing about the many women he’s loved and discarded in his 70ish years, and and how the current crop of little girls later become the next wave of eligible targets for his roaming affections.

Chevalier has another good tune with “I'm Glad I'm Not Young Anymore,” celebrating his gradual slowing in his amorous activities, which his own life inspired in a conversation with Lerner. I also enjoyed the sentimental “I Remember It Well,” shared with Hermione Gingold as Gigi’s grandmother, Mamita, a friend of Gaston’s and long-ago lover of Honoré, as they reminisce about their affair.

(Gigi’s father is never mentioned and her mother remains an unseen voice practicing opera behind an apartment door, completely uninvolved in Gigi’s life. I kept waiting for the reveal that Honoré is, in fact, Gigi’s grandfather, though that was perhaps a gimmick too far. That would also make Gaston her first cousin, once removed.)

For me, musicals tend to live and die by the songs. The best are memorable, evoke strong emotions and move the story along rather than just stopping everything for a little song-and-dance. Most of them in this film work as emotional and storytelling supports, though aside from “Little Girls” they are not toe-tappers you hum for hours and days afterward.

Story-wise, “Gigi” is thin as tissue paper. As a friend of the family, Gaston treats Gigi as a delightful child he brings caramels to at their crummy apartment. Aside from such treats, he never thinks to assist them, despite spending lavishly on clothes and then-newfangled automobiles. The costumes by Cecil Beaton, cinematography by Joseph Ruttenberg and set decoration are all exquisite.

Gaston’s various affairs get lots of attention in the newspapers — including his deliberately humiliating dumping of Liane d'Exelmans (Eva Gabor) after she cheats on him with her ice skating instructor, an action encouraged and abetted by Honoré in the name of ‘male patriotism.’

Gaston, who professes that everything about high society and romance is “a bore,” finally realizes that Gigi could be the answer to his lassitude. Mamita and her sister, Alicia (Isabel Jeans), who has been the girl’s chief tutor in the ways of the courtesan, presume this is the intended path he seeks and begin preparing Gigi for the transition.

She rejects the prospect of a kept life, knowing Gaston would eventually tire of her. He has a change of heart in the final minutes of the film — assisted by the title song, of course — and declares his heart to her.

Regular readers of this column know I loathe political takes on movies and especially abhor the scourge of presentism (judging past events and mores by a strict modern interpretation). Still, it’s hard to escape the uncomfortable gender dynamics and subtext of “Gigi,” even 65 years after it came out and more than 120 years down the road from the time it depicts.

Starting with: how old is Gigi, exactly? Based on the way she frolics with other schoolgirls in the opening scene and babyish dress, I’d guess about 14. Though maybe she’s supposed to be 16 or 17, which would at least be passable by the standards of the time. I’d postulate that Gaston is in his early 30s or so.

Still pretty creepy, given the uncomfortable adjacency to child prostitution.

For the record, Caron was almost 27 when the film came out and Jourdan almost 37, though they do a very good job of making her seem younger, accentuating her doe eyes and pouty lips. Their onscreen pairing seems earnest and invested, though both their performances have a “playing to the back of the room” tenor.

In addition to Best Picture, “Gigi” won all nine of the Academy Awards it was nominated for, then the most of all time and a clean sweep record it held until “The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King” bested it with 11. Interestingly, neither film got a single nomination in the acting categories. I’m surprised Chevalier didn’t at least get a nod for supporting actor.

Continuing my ongoing — and finally approaching its conclusion! — quest to see all the Best Picture winners, I am obligated to weigh in with my assessment of where “Gigi” stands in this exclusive pantheon. I would say in the lower quarter or so.

I was never bored or less than thrilled by its attraction as a display of magnificent sights and sounds. Its essential humanity is far less dazzling.