Reeling Backward: Robocop (1987)

Paul Verhoeven's deeply satirical take on the sci-fi dystopia genre was as much about making fun of ourselves as delivering ultra-violent thrills.

As a teenager working in a movie theater my junior and senior years of high school, one of the odd jobs thrown my way was putting up the posters and displays for upcoming movies. These would arrive weeks or even months ahead of time, and in the pre-Internet days you often only found out about the existence of a movie from these promotions in theater lobbies.

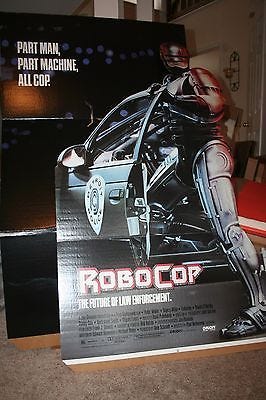

I have a very specific memory of setting up the 3-D cardboard display for “Robocop” in 1987. First, because it was fairly intricate to put together with the title character seeming to step right out of his police vehicle. Secondly and more importantly, we laughed like crazy because we thought it was the stupidest-looking movie in the history of cinema.

Part of it was the obviously low-rent, pre-CGI design of the title character, complete with the bulbous chrome dome helmet with blacked-out eye slit. More than anything he resembled one of the cylons from the cheesy original “Battlestar Galactica” TV show. And there was that over-the-top tagline: “Part Man, Part Machine, All Cop.”

For months as the July release date approached, we tittered about “Robocop” every time we passed through the lobby of the Wometco Park Triple Theatre.

Then we finally saw the movie a few days before its release — another perk of theater employment was sitting in on late-night run-throughs of new flicks to ensure the projectionist had assembled the print correctly. Our laughs turned to roars of glee.

“Robocop” was, and still is, one of my favorite films of that era.

Even as a science fiction-loving nerd in the 1980s, I recognized the deeply satirical bent director Paul Verhoeven had put on the material along with screenwriters Edward Neumeier and Michael Miner. Even as it delivered ultra-violent thrills to immature audience members like myself — it was initially given an X rating from the MPAA — its true theme was really about poking fun at ourselves.

Neumeier got the idea for “Robocop” while working as an uncredited crew member on “Blade Runner,” imagining a dystopian future where robot police officers are in danger of gaining sentience. He was also inspired by “Psycho” to kill off the main character early on — though, of course, in Alex Murphy’s case, he returns in another, highly altered form.

“Robocop” was Verhoeven’s breakout English-language film after gaining reputation for brutal, thought-provoking work in his native Netherlands. He’d also previously made 1985’s “Flesh+Blood,” a box office failure, though it has gained a cult following in the wake of Verhoeven’s subsequent success as one of the top filmmakers of the late 1980s and ‘90s.

(Probably also owing a bit to Jennifer Jason Leigh’s astonishing lack of clothing throughout the film.)

I don’t want to spend time rehashing the plot and production of “Robocop,” mostly because those things are well-known and much-discussed given the film’s iconic status in pop culture. You can read or watch a million things about actor Peter Weller’s difficulties in acting inside the Robocop costume, or how he worked with a mime to develop the character’s signature mechanical gait.

(Though one tidbit I recently learned: Weller and Verhoeven got along so badly during production the actor was actually fired, with Lance Henriksen considered for his replacement, but it would have been too much trouble to redesign the suit to fit another actor.)

Instead, I’d rather focus on the tone and humor of “Robocop.” It was and is an often hilarious film, intercut with violence and even sadism so horrific we want to turn away. So you have the scene where Murphy is brutally shot up by the gang running Old Detroit, the stump where his arm used to be spurting arterial blood while one of the crew mocks in sing-song, “Does it hurt? Does it hurt?”

And then later on another gang member, Emil (Paul McCrane) will get doused in toxic waste and melted into a mutant zombie, begging for help from his buddy, refused and then run over in a car by their leader, Clarence Boddicker (Kurtwood Smith), in a messy spew of flesh and bile that plays for repulsed laughs.

Smith’s Boddicker in many ways seems to encapsulate the tone of the picture, a jaded sort of nihilism leavened with masochistic glee at not just killing but bringing pain to others. His fare-the-well comradeship with Ronny Cox as Dick Jones, the utterly mercenary head of OCP (Omni Consumer Products), the mega-corporation that runs the Detroit Police Department, is the film’s not-at-all-subtle suggestion that street criminals and capitalistic overlords are simply two sides of the same coin.

In retrospect, junior OCP executive Bob Morton (Miguel Ferrer), who acts as the primary corporate antagonist during the first half of the film, seems almost naive in this framing. He developed the Robocop initiative as a mere contingency for Jones’ own ED-209 project to replace police with hulking, non-anthropomorphic robots instead of the cheaper cyborgs.

Jones objects to the robocops not just because they were somebody else’s idea, but because it doesn’t easily translate into widespread military sales. He calls Robo an “unholy monster,” but really he just thinks it’s an inferior money-making product. The irony, of course, being that ED-209s keep malfunctioning and blowing innocent people away.

Much has been made of the fake commercials and news broadcasts interspersed throughout the movie, which are a prime source for satirical hilarity. Now, of course, one can turn on primetime Fox News or MSNBC and see very similar self-parody… except nobody’s laughing.

Those segments, which actually open the film, were added fairly late in the going as part of Verhoeven’s efforts to get an R rating, thinking the satire would lighten up the mood of the rest of the film. Not only did it succeed, I think it actually helped turn the movie into what it became: a gruesomely pleasing mix of black humor, pessimistic musing on the state of humanity and chock-a-block bloodletting.

Seriously, imagine “Robocop” without those portions, and I think it would play very different: a very grim, super-violent spectacle about an ordinary cop who gets blasted to pieces and then brought back from the dead as a virtual slave.

His is in a lot of ways a superhero story, though of the darker sort where the character would almost certainly relinquish their powers if it meant returning to their previous life. “Robocop” is a tragic tale, but one told with a winced, wry grin.