Reeling Backward: Straw Dogs (1971)

Sam Peckinpah's brutish vision of humanity's dark inner conflict faltered in this odd rumination on manhood starring Dustin Hoffman as a Yank fending off British cretins.

Programming note: I’ll be talking about this movie on an upcoming “Medium Cool” podcast with Austin Glidden and friends, so make sure to tune in!

“Straw Dogs” was the one where Sam Peckinpah lost a lot of people.

Riding high after the critical and commercial success of 1969’s “The Wild Bunch,” Peckinpah was sent low with the box office disappointment of “The Ballad of Cable Hogue” the next year, perhaps his gentlest and most personal film. Production also ran over schedule and budget, solidifying his reputation among the studios as a talented but unreliable director.

He took “Straw Dogs” as a paying job and a star vehicle for Dustin Hoffman, and its modest commercial success saw Peckinpah established as a gun-for-hire director for the next few years — “The Getaway,” “Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia.”

But a lot of folks really didn’t like it, and it’s easy to see why.

Peckinpah’s movies were always very Y-chromosome heavy, focusing on the moral ambivalence of men and their barely-hidden capacity for violence. Womenfolk were generally kept on the side as pretty playthings. With “Straw Dogs,” we saw man’s potential for evil aimed squarely at females, including a rape scene in which the woman takes pleasure in the act after a pro forma resistance.

Really, the whole piece is an odious rumination on manhood — and neither men or Peckinpah come out looking too well.

Hoffman plays David Sumner, an American mathematician who has recently moved to the English moors in the hamlet of Wakeley, where his British wife, Amy (Susan George) was raised. They actually bought her father’s old place, Trencher’s Farm, and are having it fixed up some local men, including a new roof for the garage and trapping all the various rats on the property.

With his diminutive stature, canvas sneakers, glasses and wardrobe largely consisting of sweaters that make him look even smaller, David is instantly resented by every red-blooded Englishman in the vicinity. The cast lustful eyes at Amy, who seems to represent all the negative stereotypes of the modern liberated woman without any of the virtues.

She goes about braless and seems to take special delight in teasing the local men, but she doesn’t have any kind of career or do much of anything worthwhile. I suppose Amy keeps house, of a sort, but mostly she sits around irritating David or demanding that he turn his attention away from his work and place it on her.

There’s a vague reference to him having fled or been pushed out of his American university in some kind of imbroglio — possibly over the Vietnam war — and David received a research grant involving math and astronomy. If Amy is pleased by flaunting her body — even deliberately standing topless near a window just yards from where the man are working — David is all too happy to leave inquirers confused about the exact nature of his egghead work.

Amy and David’s relationship is ostensibly loving, but also in many ways poisonous and competitive.

His beta-male ways are viewed as sweetness by Janice (Sally Thomsett), the teenage tart-in-training in the village. But all the men see him as weak and privileged, and are jealous that he married the prettiest girl in their parts.

The chief antagonist is Charlie Venner (Del Henney), with whom she used to go back in the old days, and he clearly would like to bring them around again. He’s hired by David to work on the house, supplementing Norman Scutt (Ken Hutchison), a sallow-faced fellow, and Charlie’s brother Bobby (Len Jones). There’s also Chris Cawsey (Jim Norton), the amiable rat-trapper, who always has a tittering laugh at the ready.

In town the ringleader of the riffraff is Tom Hedden (Peter Vaughan), a bearish older man who spends most of his time quaffing pints at the local pub where everyone gathers. (The sign out front calls it the Green Shield Tavern, but the bartender answers the phone as Wakeley Arms — possibly just a continuity error.)

The local magistrate is Major John Scott (T. P. McKenna), who despite having one arm in a sling (presumably a war wound) is the only person who can keep Tom, Charlie and the rest in line.

Charlie and his colleagues deliberately slow their work on the house to a crawl, mostly so they can ogle Amy, look for things to steal in the outbuildings and make fun of David. Things take a sharp turn when they find her cat hung by its neck in their bedroom closet. Amy immediately suspects Charlie of being the culprit, and grows increasingly hostile to David for not confronting him over it.

David has a queer way of ignoring the threats and mockery of the men, as if they are beneath him, which only antagonizes them more. They lure David out to the moors to hunt ducks, but really a ruse for Charlie to sneak back to the house and seduce Amy. This starts out as an unmitigated act of violence, but halfway through she begins reaching up to kiss him and encourages his thrusts.

This is hard to watch. It feeds into all sorts of foul mythology surrounding rape culture, and explicitly showing that Amy did indeed want it — if not at first — makes for a situation that is not morally ambiguous but simply depraved.

If this is not bad enough, immediately afterward Scutt sneaks into the house and, at gunpoint, forces Charlie to hold Amy down so he can rape her from behind. This is depicted obliquely, perhaps owing to the content restrictions of the time, but the juxtaposition of the two violations — one welcomed, one not — is sordid.

An uncredited David Warner plays Henry Niles, the local outcast who is the only man more resented than David. Tall, foppy-haired and using a cane — for support rather than British affectation — Henry has the mind of a child but apparently had some kind of offense in his past involving children and/or women.

During a huge church social that everyone attends, Janice lures Henry out do a barn to seduce him, but then the townsfolk get wind of it and set to chase them. Henry inadvertently strangles her to death out of fear, then runs out into the foggy road and is hit by David and Amy in their car. They take him back to their place to call the doctor, but then Tom, Charlie and the rest find out Henry is being protected there and lay siege to the house.

They want to get their hands on Henry, but also punish David for his upstart superiority.

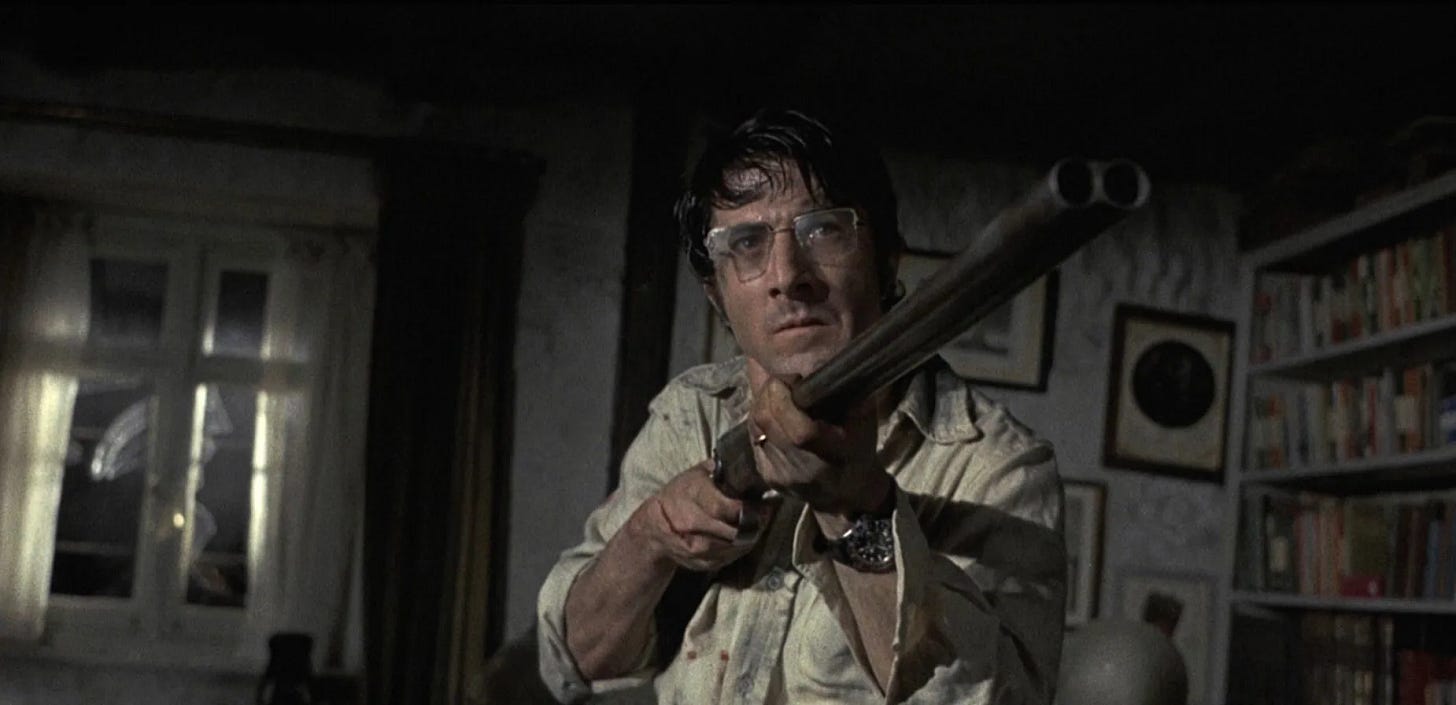

Indeed, “The Siege of Trencher’s Farm” is the name of the book (by Gordon M. Williams) upon which Peckinpah and David Zelag Goodman based their screenplay. The assault lasts for a good half-hour or so, with an unarmed David fighting off the men outside with their shotgun using just his wits. Amy at first demands that David simply hand Henry over to them, which he refuses to do out of mix of empathy for a troubled soul (he does not know about Janice’s murder) and an almost feudal sense of the sanctity of property.

"I will not allow violence against this house,” he proclaims.

The last bit is quite a tense, and in many ways reminded me of “Night of the Living Dead” and other early zombie flicks where a horde of vaguely human attackers are trying to beat down doors and smash in windows. David defeats them with a combination of boiling water, a fireplace poker and an old man-trap that he’d had mounted up on his mantle.

When it’s all (almost) over, David is almost giddy with glee, having embraced his manly propensity for violence and come out on top. “Jesus I got ‘em all!” he practically squees.

As a psychological thriller, “Straw Dogs” succeeds as a slow-burn buildup to a heart-pounding confrontation. But its ugly depiction of gender-based power struggles is disturbing without any sort of insight. It’s a movie with lots of heat but no light.