Reeling Backward: The Entertainer (1960)

Christopher Lloyd finally punches his ticket to see one of his white-whale classics starring Laurence Olivier as a has-been vaudevillian, and comes away throwing tomatoes.

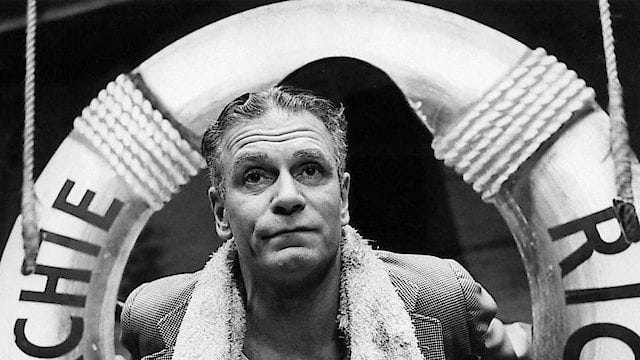

“The Entertainer” has been one of my white-whale classic films. I’ve been meaning to see it for years, possibly even as much as a couple of decades. At some point I saw Laurence Olivier done up as Archie Rice, nearly unrecognizable as the pitifully washed-up vaudevillian, and was entranced.

Perhaps it’s because our sense of Olivier is so tied to an air of refinement, of education and genteel manners, that seeing him as a crass showman generated a jarring cognitive dissonance that registered with me as, if not pleasurable, then decidedly profound.

Alas, urgency was not a guarantee in this case.

For a long time it was not available on physical media, or other films pushed themselves to the fore, or I just plain misplaced it in my priorities. Part of the aspect of the Reeling Backward project is I like for there to be an air of serendipity, of discovering new-old films through my own organic wandering. So though I keep a list, I don’t impose timetables or ordering.

Finally “The Entertainer” turned up on Turner Movie Classics, and the time had come. TCM is a fantastic resource, though movies are generally only available on there for about a month at a time. I’ve often had things I put on my watch list slip away before I could get to them. I think this film was one of them a few years back.

And so after all that waiting, that powerful (though intermittent) anticipation… I really, really didn’t like the movie. In fact, I felt tempted to throw tomatoes.

Oh, it’s a terrifically made film. In addition to Olivier’s Oscar-nominated performance, it’s got wonderful production values and stunning ugly/beautiful cinematography (by Oswald Morris) that deliberately lends everything a chintzy, run-down and inauthentic feel. We can practically smell the mothballs in Archie’s aged costumes, the oily emanation of his severe, middle-parted hair style.

The supporting cast, which includes Joan Plowright and Brenda de Banzie, is a terrific ensemble, and the movie even boasts the distinction of being the screen debut for both Alan Bates and Albert Finney.

And it’s just… old. So very old and musty. Familiar, is the polite term. Derivative, a better descriptor.

Based on the play by John Osborne, it seems almost a British knockoff of Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman,” a tragic look at a nobody plying his trade to an unappreciative clientele, his professional failures dragging down his family like an anchor. The Brits referred to 1950s/60s plays and movies of this ilk as “kitchen sink dramas,” gritty and focused on blue-collar antiheroes.

Watching it, I felt like I knew everything that was going to happen before it did. By the time these things actually came to pass, they had already lost any emotional weight. Olivier’s Archie is a self-destructive petty tyrant, lording it over his family and troupe of unpaid actors and crew, who then transforms into a mewling supplicant when things don’t go his way.

He has no redeeming characteristics, and the truth is spending nearly two hours with him feels less like scouting the soul of a noble failure than time wasted in a bar listening to a tinny piano accompanying a drunkard stumbling through a story, half-remembered and half-BS.

Set in 1956, the story takes place in an unnamed British seaside town (shot in Morecambe), once a thriving post-WWII entertainment mecca for the masses that is slowly deteriorating into irrelevance. Archie’s shtick was already aging even before that heyday, a throwback to the vaudeville/burlesque tradition of a song-and-dance comedian who adorns his background with lovely ladies in whatever minimum state of dress the local morals will accommodate.

His father, Billy Rice, was a giant of this genre from probably about the turn of the century to a few years ago, when age and apathy finally forced his retirement. He’s played by Roger Livesey (best known for “The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp”), despite being just 13 months older than Olivier. I’m guessing Archie is supposed to be in his early to mid 50s, and with makeup and an appropriately statesmanlike demeanor by Livesey, Billy convincingly embodies a gent in his 70s.

Archie is but a pale shadow of his pa talent-wise, and both men know it. And yet he is compelled to stage show after show each season using the same old formula, despite ticket buyers growing increasingly scanty. He had to declare bankruptcy a few years ago, which has still not been discharged, so Archie is under constant threat of going to jail, and as a result does business under his wife’s name.

(Nevertheless, as often is the case with depictions of the downtrodden, there is somehow always enough money for an unbroken chain of booze and smokes.)

Speaking of the missus, Phoebe (de Banzie) is in ways more obviously pathetic than Archie. A higher-class woman who dallied with him while he was still married, Phoebe is forced to work as a shopgirl despite her age, and now lives a life of regret made muddier by her frequent drinking. Archie, at least half an alcoholic himself, does not discourage this and in fact seems to view her stuporous spells as a reprieve.

Olivier originated the role on the stage, and so was the obvious choice for the screen version, directed by Tony Richardson from a screenplay adaptation by Osborne and Nigel Kneale. Reportedly Olivier even filed his two front teeth to create Archie’s distinctive gappy grin.

Plowright plays Archie’s daughter, Jean, by his first wife, who conveniently died shortly after he betrayed her with Phoebe. As the story opens, she has returned home after a long absence living in London, a failed painter who is resigned to teaching art to rascally lower-class adolescents. She is engaged to Graham (Daniel Massey), a promising young businessman who is pressuring Jean to go with him on a plum assignment in Africa.

Ostensibly she returns to see her eldest brother, Mick (Finney), off to war in the Suez Crisis — which she has recently participated in political protests against. But we sense the real reason is she wants to see if there’s any chance of reconciliation with her father. Middle son Frank (Bates) acts as Archie’s right-hand man in all his endeavors, but underneath is itching to make his own mark in anything other than the family business.

Archie is an incorrigible philanderer, something he doesn’t even bother to hide from Phoebe. His latest conquest is Tina Lapford (Shirley Anne Field), a 20-year-old who won second place in a beauty contest Archie emceed as a last-minute replacement. He’s interested in her tender young flesh, of course, but also the money her wealthy parents seem willing to invest in a show at the prestigious Winter Garden Theatre if Tina is given a starring role.

He actually sounds Jean out on this idea to get her reaction. We can practically see the wheels of his lizard mind whirling, calculating if he can simultaneously pull off closing out his current show (preferably without paying his actors their back wages), moving his moth-ridden act to London, divorcing Phoebe and marrying young Tina.

Part of him knows he’s ridiculous, but he can’t resist fumbling attempts to put himself back on top again — or, at least, as close to the top as Archie has ever seen.

Archie has a lucrative offer from Phoebe’s brother to move to Canada to manage a new hotel he is opening, a practical guarantee of lifelong stability and prosperity. But Archie jokes you can’t get Draft Bass ale in North America, because for him anywhere but up on the stage is a torture.

Archie’s act is pure hokum, an aging lothario who paints in his graying hair and vanishing eyebrows, chasing his semi-naked dancers around the stage. The audience is supposed to be in on the joke that it’s not really funny, a la Henny Youngman’s “take my wife please” routine. But Archie long ago lost, or maybe never had, the ability to rope the people inside his self-delusion.

He always closes his act with a rendition of the John Addison song, “Why Should I Care?” It’s both insouciant and bittersweet, a man proclaiming his indifferent to how people perceive him, when in fact it’s everything that drives him. Archie craves adulation — from his audience, from his colleagues, from his family — even in the tiny dribs and drabs his meager talent can evoke.

Late in the film, the seemingly inevitable news arrives that Mick has been killed in Egypt, and it barely seems to register with Archie at all. He leverages the media fanfare surrounding his son’s hero’s funeral for yet one more go on the stage, even recruiting the aging Billy to be his front man. The oldster is game but kicks off before taking the stage for the first time. The tax men circle, ready to pack him off to debtors’ jail.

All these tragedies are but trifles to Archie; to him the only one that matters is getting the final hook out of the spotlight.

It is indeed a compelling performance by Olivier, and I’m not entirely sure why I felt so totally emotionally disconnected from it. Maybe it’s because Archie Rice doesn’t just harm himself but is completely unconcerned with the fate of those around him — all of them chattel to be pitched into the fire to feed his paltry ambitions.

“The Entertainer” is the story of a man so unworthy, it almost seems better left untold.