Reeling Backward: The Last of the Mohicans (1992)

Michael Mann's sweaty, lusty revision of James Fenimore Cooper's historical novel is a paean to the power of moving images and music to stir the blood.

Michael Mann’s “The Last of the Mohicans” is the ultimate triumph of style over substance. I mean that as a compliment.

In 1992 Mann was still mostly known as the guy behind the “Miami Vice” TV show, hugely popular as much for its slick production values as its gritty crime stories. He’d already made the excellent “Thief” and “Manhunter,” but they hadn’t broken into the public consciousness like “Vice” did and “Mohicans” later would.

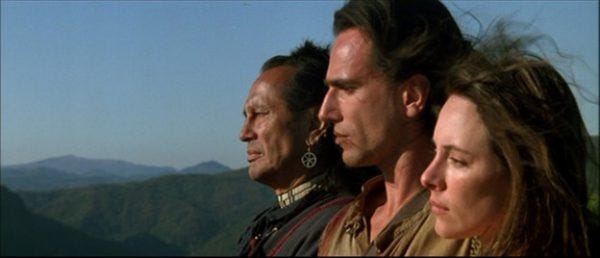

I have a vivid recollection of a critical mass of American womanhood performing a collective swoon for Daniel Day-Lewis as Nathaniel “Hawkeye” Poe, the sullen and smoldering star of the show. With his long, black tresses, fierce gaze and indifferently adhering tunic exposing the ultra-lean, hairless torso that was just coming into vogue at the time, Day-Lewis made his bones as a serious actor with “My Left Foot” but became a star with “Mohicans.”

A white man raised by a Mohican Indian father, Hawkeye was a long-recurring character in Cooper’s novels (once a staple in schools but unread by me) known for his unerring accuracy with a flintlock rifle. He bore many names in Cooper’s stories — Natty Bumppo, Deerslayer, Pathfinder, etc. Hawkeye considers himself an Indian, and most of the different tribes accept him as that and call him “Long Rifle” in their respective tongues.

One of the interesting things about the story, set in 1757, is the authentic depiction of the relationship between the Native American peoples and with the French and English colonialists then squabbling over control of the New World. At that time upstate New York was considered “the frontier,” and both sides liberally allied themselves with Indians and supplemented their armies with native warriors and scouts.

We’re reminded that the tribes freely trafficked in slavery, torture and patriarchal subjugation long before Europeans landed with their own particular vices in tow.

I was struck by the frequent use of the word “father” to describe any sort of authority or action to which a tribesman considers himself beholden. E.g. Magua, the main villain played by Wes Studi, a Huron enslaved by the Mohawks who acts as a turncoat against the English, refers to the French general Louis-Joseph de Montcalm (Patrice Chéreau) as his “French father,” while his mortal enemy is British Col. Edmund Munro (Maurice Roëves), whom he calls “Gray-Hair” and believes is the father of all his misery.

In Hawkeye’s case, the use of the term is more literal. His adoptive father is Chingachgook (Russell Means), the last war chief of the Mohicans, an actual tribe somewhat fictionalized by Cooper. In the books Chingachgook is Hawkeye’s foster brother rather than his father, and biological son Uncas (Eric Schweig) is actually the titular last of his kind. Until, that is…

Their little family unit is fiercely independent, determined to stay out of the French-English conflict, traveling about subsisting as hunters and trappers. Their skills with rifle and tomahawk are unmatched, and Chingachgook’s massive gunstock war club is practically a character unto itself.

The Mohicans are friends with many of the settlers, and so are disposed against the Huron who have been raiding up and down the frontier. This is perhaps the biggest change from the book, in which Hawkeye is explicitly an English scout.

The story (Mann wrote the script with Christopher Crowe) introduces an entire subplot about the tensions between the colonists and the English, personified by Munro, who conscripts the men to defend Fort William Henry and then refuses to release them to defend their homes against the Indian raids.

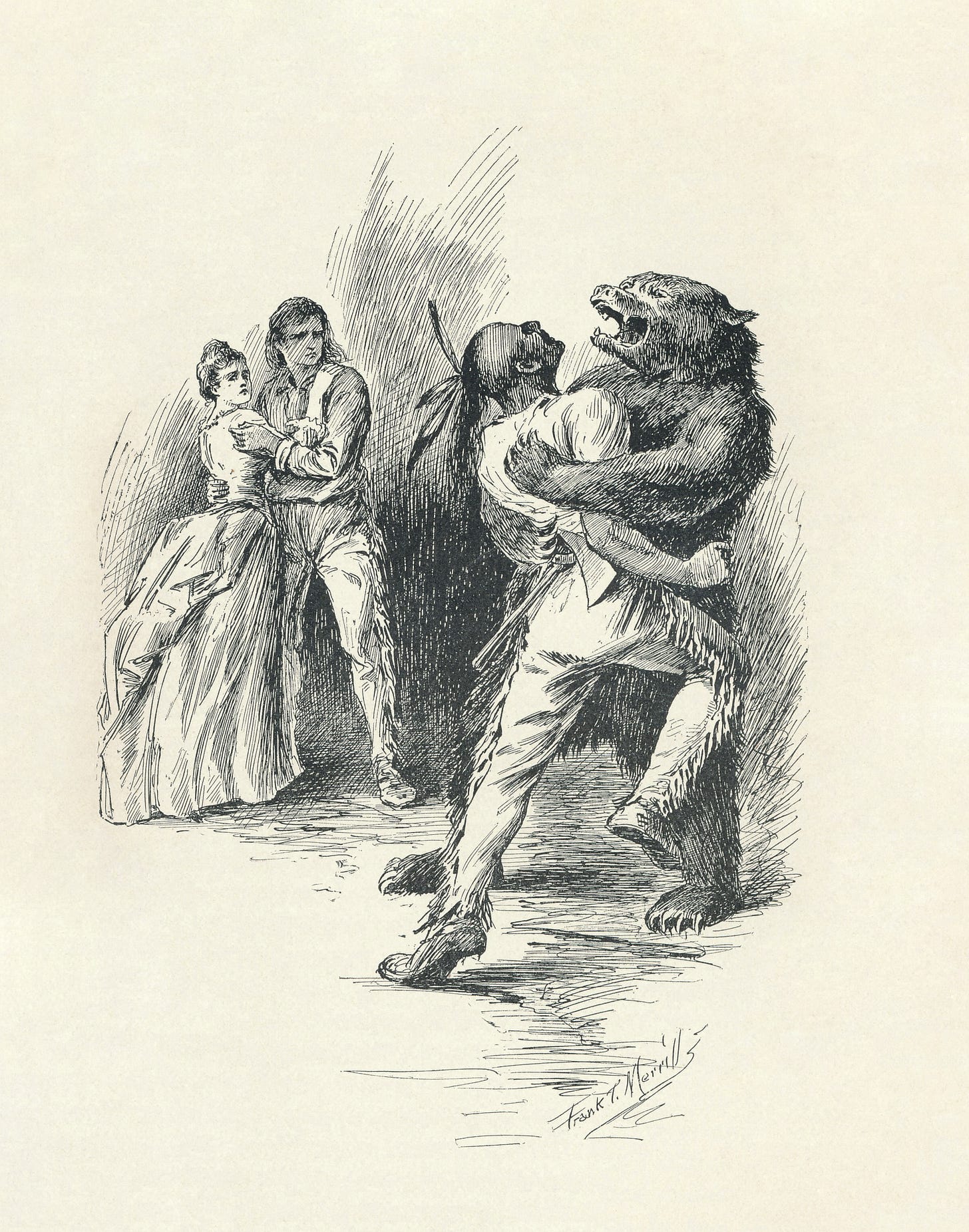

Other than that, the movie’s plot more or less follows the book pretty closely, at least through the first couple of acts. After Magua captures Munro’s daughters and presents them to the Huron chief for judgment and acknowledgement of his war victories, Cooper goes off into a whole strange labyrinth of twists and deceits, including Hawkeye disguising himself as a bear.

“Mohicans” has generally been described as a romance, and Hawkeye’s relationship with Cora Munro (Madeleine Stowe) is notable for the complete lack of anything resembling normal courtship protocols of the era. There’s just a lot of staring, some verbal sparring that mellows into musings on their cultural differences, and then one make-out session where he simply grabs her by the hand at the fort, pulls her into a dark corner and they canoodle steamily.

(Without even so much as a corset being lifted, it should be noted.)

Hawkeye, his father and brother rescue Cora from an attack by Magua and his Hurons, also saving her teenage sister, Alice (Jodhi May) and Major Duncan Heyward (Steven Waddington), a childhood friend who is escorting them to the fort to join their father, unaware it is currently besieged by the French. Duncan is used as a secondary antagonist, a competitor for Cora’s affections who clashes with Hawkeye but finds fiery redemption in the end.

From a storytelling perspective, it’s amazing how simplistic this film really is. There are essentially only three events: the trip to Fort William Henry; the battle there; and an extended chase sequence after the English surrender.

Mann employs sweeping camera movements and bold angles to make the audience feel the grand, epic canvas against which this human story plays. Trading in the dank cityscapes that had been his stock in trade, the director uses the lush, timbered forests and prehistoric outcroppings of mountainous stone as a way of reminding us of the then-untamed nature of the land the people fighting over domain of it.

Possibly the movie’s biggest stumbling block is the dialogue, written in a deliberately archaic way (I’m guessing straight from the novel) that can sound very tongue-twisted and formal when the actors are called upon to spout it. Even Day-Lewis, no slouch when it comes to dialects and accents, comes across a bit stiff at times, including the movie’s biggest emotional crescendo where Hawkeye must temporarily abandon Cora and Alice to Magua:

“You're strong! You survive! You stay alive, no matter what occurs! I will find you! No matter how long it takes, no matter how far. I will find you!”

No discussion of the movie’s mood could go without mentioning the iconic musical score by Trevor Jones and Randy Edelman. Oddly out of place with its repetitious sawing of strings — the main theme borrowed from Scottish songwriter Dougie MacLean — it almost sounds more like swaying sea shanty. And yet, it just works. I couldn’t imagine the film without it.

The evocative nature of “The Last of the Mohicans” as a piece of pure cinema is a paean to the power of moving images and music to stir the blood (to borrow a phrase from Cora) despite its scanty story structure. It’s the sort of moviemaking that is very easy to sit back and mock, but while you’re watching it’s an incredibly visceral experience.

Interesting article. I don't get what you mean by the Mohicans were invented by Cooper. They were one of the Algonquian tribes, and actually existed.