Reeling Backward: The Long Goodbye (1973)

Robert Altman's modernized take on film noir is bleak and beautiful, though not the ha-ha send-up of the genre as it's been described.

I’ve heard “The Long Goodbye” described as a send-up of the film noir genre, with funnyman actor Elliot Gould recast as private detective Philip Marlowe in a story by Raymond Chandler set in (then) modern times.

But I don’t see it that way — in fact, I don’t think it’s a comedy at all.

Director Robert Altman was not exactly a guy known for making outright ha-ha films; dramas, satire and sardonic takes on genre pictures were more his speed. “The Long Goodbye” belongs more in that latter grouping, a dead-serious look at the crimes of the wealthy that, despite a very smirky protagonist, contains zero jokes.

Altman, hot off of “M*A*S*H*” and “McCabe and Mrs. Miller” after a long apprenticeship in television and documentaries, got the gig after Howard Hawks and Peter Bogdanovich turned it down — though the latter recommended Altman. Upon launching production he dubbed it “a satire in melancholy.”

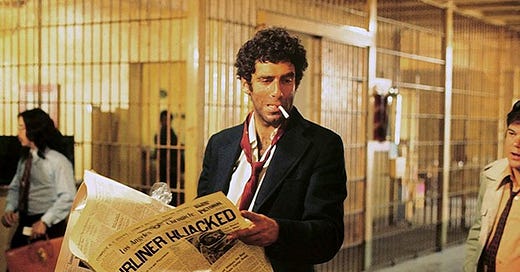

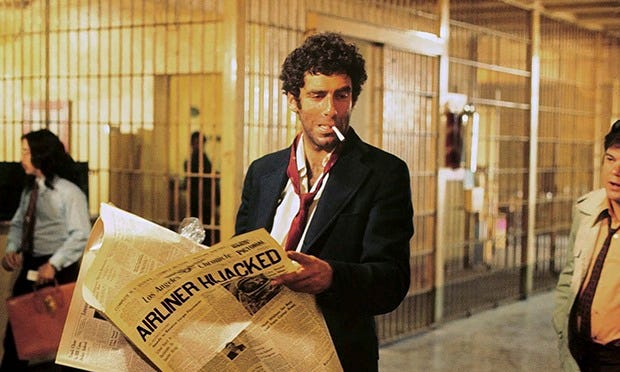

Gould’s version of Marlowe is a walking anachronism dwelling in 1973 Los Angeles but more fitting for a quarter-century earlier. He wears a suit and tie everywhere he goes, even if it’s a bit shabby, with omnipresent cigarettes in his mouth that he lights with non-safety matches struck on whatever object or furniture he happens to be passing by. He spends a lot of time at a seedy tavern that doubles as his unofficial phone service and drives an olive green 1948 Lincoln Continental. (Gould’s own personal vehicle.)

Marlowe is a real mouthy SOB, and his signature M.O. is to give a bunch of lip to whoever’s currently pressuring him — police, gangsters, rich elites. He gets a lot of smacks and punches for his wiseacre act. At one point he’s threatened with castration, and doesn’t break his patter one bit.

Even when nobody’s around, Marlowe carries on a soliloquy, as if arguing with himself or commenting on the latest travesty befalling him. Gould gives the character an insouciant, hangdog charm.

The book had never been turned into a movie before — one of only two by Chandler at the time — and they brought in Hollywood legend Leigh Brackett to write the script, having done the adaptation of Chandler’s “The Big Sleep.” She pared down the convoluted plot to a tight 112 minutes revolving around the apparent death of his friend and a missing alcoholic writer, two seemingly unconnected cases that keep crossing paths with Marlowe as the guy stuck in the middle.

You can already see some of the techniques Altman would employ in his masterpiece “Nashville” a couple of years later, including the camera seeming to wander away from its subjects during a conversation and overlapping pieces of music or dialogue intruding upon the soundscape. Here it gives the story a loose, almost jazzy feel.

Speaking of music, John Williams supplied the laidback score as well as the title song in conjunction with Johnny Mercer. It’s heard several times through the movie — on a radio, as background or even a piano player practicing it at the bar. The lyrics point to how hard it can be to end a spiraling romance, though in the context of the movie it’s more about Marlowe’s obstinate unwillingness to let anything go.

Marlowe is like an amiable but cynical dog with nothing much to do, but once he gets his teeth in a bone he passive-aggressively refuses to let go.

He lives in a lonely walk-up apartment with his cat, who will only eat Coury brand cat food. In an amusing opening segment, he runs out and can’t find any at the grocery store, so he buys another brand and goes through an elaborate ruse to put the new cat food in one of the old Coury cans, even going so far as to close the kitchen door so his cat won’t see the switch.

I liked this bit, which might seem like a time-waster that takes up about the first 10 minutes of the movie. But it shows Marlowe as a guy who, while seemingly lackadaisical, is willing to go through extreme ends once he’s got a mind to do something.

It also gives a chance to show off his neighbors, a foursome of beautiful young women who lounge about in various states of undress all the time, doing yoga or stoned or both. Marlowe talks neighborly to them and does occasional favors, but doesn’t seem the least bit interested in them sexually.

His old buddy Terry Lennox (played by baseball player-turned-author Jim Bouton of “Ball Four” fame wearing a horrendous blond wig or dye job) turns up on his doorstep with bloody knuckles and a scratched cheek, the result of another go-around with his wealthy wife, Sylvia (never seen). Terry asks Marlowe for a ride down to Tijuana to escape the troubles, and he obliges.

The next morning the cops show up to hassle him about Terry, running Marlowe down to the station on a clapped-up charge of assaulting an officer. He gives them absolutely nothing but wisecracks until the lieutenant reveals that Sylvia is dead. Suddenly serious, Marlowe insists that despite their marital fights Terry isn’t the killing kind. After three days in jail, he’s released and learns that Terry committed suicide in Mexico.

He’d probably head down there to check it out himself, but a new case present itself. Eileen Wade (Nina van Pallandt), the wife of a famous writer, Roger (Sterling Hayden), hires Marlowe to track him down after he disappears on one of his drinking binges. He soon locates Wade at an exclusive private treatment center run by the creepy Dr. Verringer (Henry Gibson, soon to be an Altman favorite). Despite being a foot shorter than the bearish Wade, the not-so-good doctor seems to have Svengali-like hold on the writer.

The Wades are reunited but not any happier. Marlowe nurses an ongoing flirtation with Eileen, and finds himself drawn to the brash, fatalistic Roger, played by Hayden as a bipolar Hemingway type. He soon commits suicide by diving drunkenly into the ocean.

Rather than the glitz of Beverly Hills, the majority of the story takes place in the beachside idyll of Malibu, where everyone is rich and connected to each other. Marlowe suspects more of a link between the Lennoxes and Wades than anyone is letting on.

The key figure not in the book is Marty Augustine, played by Mark Rydell, better known for his directing (“On Golden Pond”), a local hood who says Terry owes him $355,000 that was supposed to be delivered in Mexico but never showed. Since Marlowe is known to have driven Terry down there, Marty figures the private eye knows where the money is.

Marty bears a lot of resemblance to Roman Polanski’s character in “Chinatown,” which came out a year later. They’re both diminutive, well-mannered creeps prone to sudden fits of horrific violence. Instead of bloodying up Marlowe, Marty takes out his wrath on his own girlfriend, slicing her nose open with a broken bottle. “That’s someone I love, and I don’t even like you!!” he thunders in warning.

In their second meeting, Marty insists they both strip off their clothes to prove they have nothing to hide to each other. The crime lord always has a gaggle of toughguys around to protect him and act as his yes-man chorus, and makes them comply as well. (One is Arnold Schwarzenegger, in an uncredited cameo.)

Just when it seems Marlowe is finally going to see his bulltalk catch up with him — Marty instructs one of his goons, whose father was a mohel, to “cut it off” — the missing money is delivered.

The private dick keeps his, but doesn’t seem too excited about it.

I was a little confused about this plot point. It’s revealed that Terry is alive and well in Mexico, and that he and Eileen were having an affair, just as Sylvia and Roger were (an unintentional 1970s-style wife swap, it would seem). He faked his death after killing Sylvia when she found out about his affair (or possibly hers, or maybe both).

Marlowe tracks Terry down in a remote villa, and the old chum brags about now having a girlfriend richer than even Sylvia or Marty, and admits to having used Marlowe. I guess the idea was Terry returned the stolen money, since he doesn’t need it anymore — but why? Marty thought he was dead, and all the screws were being turned on Marlowe. (Who plugs his friend for his troubles.)

I enjoyed some of the more colorful supporting performances in the film. David Adkin, who had small parts in a bunch of Altman films, plays Harry, a hapless young member of Marty’s crew who is assigned to follow Marlowe. He’s gobsmacked by the nudist neighbors, and bumbles his tail job so badly that Marlowe enters into a running banter with him — even supplying the address of where he’s going in case Harry gets lost.

I couldn’t find a credit for the gate guard at the Malibu complex where everybody lives, who whips out Hollywood impressions for entertainment. In a nod to the throwback nature of “Goodbye,” they’re Golden Age staples like Jimmy Stewart and Walter Brennan.

So what exactly is “The Long Goodbye?” My take is it’s not a satire of film noir but a modernized nod to the genre that playfully tinkers with the different time periods to comment on both. Elliot Gould’s Philip Marlowe is a puckish rebel in the Humphrey Bogart mold who seems like he’s laughing at a joke known only to him.

It’s a strangely bleak and beautiful movie, and closer to sadness than comedy.