Reeling Backward: The River (1984)

A flop when it came out 40 years ago with a purportedly miscast Mel Gibson, Mark Rydell's unironic look at struggling Tennessee farmers deserves a reappraisal.

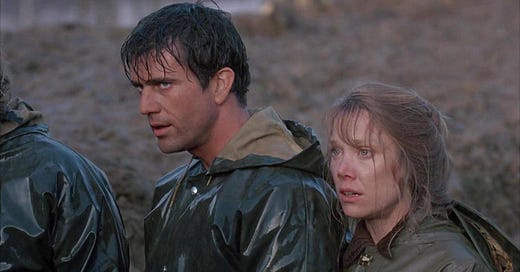

Everybody who claimed to know anything about movies in 1984 said Mel Gibson was badly miscast in “The River,” Mark Rydell’s unironic look at struggling Tennessee farmers.

Known at the time only for his roles in the Mad Max movies, “The Year of Living Dangerously” and “Gallipoli,” the showbiz pundits could only envision Gibson with a heavy Australian accent, or maybe a faux British one from “The Bounty,” released a few months earlier.

Rydell himself was completely opposed to casting Gibson, until he personally auditioned with a Tennessee twang he’d spent months working on. It didn’t stop the subsequent deluge of criticism for his performance. Heck, Gibson himself later said it was a mistake for him to take the role, dubbing himself “too pretty” to play a hardscrabble farmer.

Not sure if that counts as hubris, because Gibson was indeed quite winsome and lithe back then. Maybe a Harrison Ford, with his good-looking but blunter features, could’ve pulled it off better.

(Personally I have never been called too pretty for anything, even movie critic — the only profession more troglodyte-esque than radio DJs.)

You know what? I think everyone was wrong.

Gibson is just fine in “The River,” gruff and believable as a blue-collar mule of a man. Though the real star is Sissy Spacek as the matriarch of the clan. She was a natural casting choice after the success of “Coal Miner’s Daughter,” and is utterly convincing as a tough farm girl who always chooses the harder road with a purpose than the easy, empty option.

It’s one of her finest turns, for which she scored an Oscar nomination.

Rydell was just coming off the massive career lift of “On Golden Pond,” including an Oscar nomination of his own, and opted to direct this original screenplay by Robert Dillon and Julian Barry (“Lenny”). Though fictionalized, it was inspired by actual accounts of heartland farmers fighting off floods, droughts, bank foreclosures and scheming moneymen.

It was the sort of moviemaking that could be embraced by both the Reagan-era nostalgists and their critics. Problem was, released in December it was the third such themed film to come out in 1984, with “Country” starring Jessica Lange and “Places in the Heart” starring Sally Field being released within a week of each other in September.

Farmer fatigue, more than anything, seems to account for the soggy box office for “The River,” which cost $18 million to make but brought in only $11.5 million.

Having missed its initial release, I finally caught up with the film just as it was leaving Netflix, and came away impressed by the film’s grimy poetry. The musical score by John Williams is understated and lovely, and the cinematography by Vilmos Zsigmond has a homespun sweep. (Both also got Academy Award nods, along with Best Sound.)

It seems to me it’s seriously deserving of reappraisal.

Not to mention it features Scott Glenn, my all-time favorite “that guy” character actor, who receives highest billing after Gibson and Spacey. He plays the heavy, Joe Wade, who runs Leutz Corp., the local milling company, and keeps the valley farmers under his thumb. He’s also got an evil plan to run out the farmers nearest the river so they can dam it up and irrigate the whole valley.

(Actually, an entirely sensible bit of regional economic planning that would benefit everyone, assuming Joe would fairly compensate the affected landowners rather than underhandedly sabotage them. But then, you don’t have a movie.)

There’s even a subplot about Joe and Spacey’s character, Mae Garvey, having once been an item… with mutual home fires still warm for each other. Tom Garvey (Gibson) is constantly watchful and resentful, and though he seems to know Mae would never actually betray him, the love triangle stokes a rivalry between Joe and Tom that seems to go back to their youths.

“This is my home place, Mae. My people are buried here,” Tom says when it’s suggested they should sell out to Joe and make a fresh start elsewhere.

Tom is the hardest-working and stubbornest farmer in the modest farming community of Franklin. (That’s the name of a real Tennessee town but it’s a suburb of Nashville; the film was shot in the Holston Valley area of Church Hill.) The running theme with Tom is he won’t accept anyone’s help, whether offered with an honest hand or one hiding a weapon. He works his 320 prime acres sunup to sundown, with only his kids to assist.

He and Mae have a son, Lewis (Shane Bailey), about 12, a loyal learner at dad’s knee, and a girl, Beth (Becky Jo Lynch), around 6, with a deep love of animals and tomboyish short mop of hair straight out of the Scout Finch school of casting. Their job is to react to whatever mom and dad are doing, and accept not a little verbal abuse from Tom.

No doubt this also contributed to Gibson being seen as an overly hard, unsympathetic figure to audiences.

The story opens and closes with massive floods that threaten to spill over the levees and wash out the crops of the Garveys and their surrounding neighbors. After losing his tractor in the first deluge, Tom goes into town to ask for a third mortgage from Howard (chrome-domed icon James Tolkan), the town banker, unaware he’s in the pocket of Joe.

Tom manages to plant his corn crop for next season, but even after selling off every scrap of equipment and things they can spare — even Mae’s hand-woven quilt — they find themselves still short. So Tom is convinced by his cousin, Harve (Billy "Green" Bush), to take a job at the massive Midland Iron Fabrication.

The pay is crap: $4.25 an hour for 50 hours or $225 a week — about $681 in today’s dollar. The foreman is a tin pot dictator and the work is nasty and dangerous. It’s also a long ways away, so Mae must watch over the farm while Tom is gone for months at a time.

Worst of all, when Tom and the others arrive they find themselves attacked by the striking workers who used to slave away at the foundry. “We’re scabs!” one of the other guys in the truck yells, and we can see all sense of self-worth drain out of Tom’s face and those of his fellows. Nonetheless, they stay so they can get paid, figuring it’s hard all over.

This subplot resolves with perhaps the film’s most tense and memorable scene. The strikers sign a new contract, and Tom and the other scabs are given one hour to gather their stuff and leave — but without any trucks to provide a semblance of safety from the rock-throwing, 2x4-wielding antagonists.

Pushed out into the crowd of surly strikers, with whom they’ve already exchanged beatings, we expect a total blood-letting melee to break out. Instead, the strikers part like the sea and allow Tom and the others to march out with their heads held low, the pay in their pockets insufficient to forgive their shame. A woman with a crying baby stands in Tom’s way just to spit in his face.

(Clearly, she was waiting for the prettiest one.)

On the homefront, the most notable event is Mae getting her arm caught in a piece of farm equipment while trying to fix it, and nearly dies from the loss of blood. She escapes only by coyly antagonizing their bull so he charges the plow she’s trapped under, jerking her arm out of the gears. Joe is there to take her to and from the hospital, and pitch some woo as well.

“This kind of life is over. Can't you see that?” he offers.

Things end rather predictably with another flood and a face-off between Tom and Joe, with the latter recruiting a small army of castoff farmers living in a shantytown to come and tear down the levees and flood the Garveys out, once and for all. Turns out one of them was a young coworker of Tom’s from the foundry, so he gets to see things from the other side.

“The River” isn’t a particularly political or anti-capitalist film; it just follows the quotidian toils of the Garveys and people like them with unabashed empathy. Joe Wade represents the cold, calculating face of progress, though with a Machiavellian spin that seems to belong to the 1930s rather than ‘80s. Joe and Tom both sprouted from the same soil, but clearly were nourished in different ways, leading to vastly divergent fruit.

It ain’t “The Grapes of Wrath,” but “The River” is a noble and worthy entry in the rather underpopulated genre of movies about the people who work the land to feed all us tenderfoots. Seems like we’re due for another crop.