Ride the High Country (1962)

"Pardner, do you know what's on the back of a poor man when he dies? The clothes of pride. And they're not a bit warmer to him dead than they were when he was alive. Is that all you want, Steve?"

"All I want is to enter my house justified."

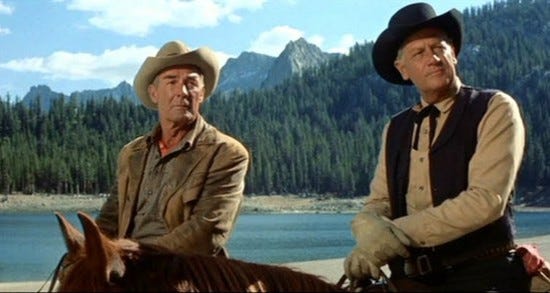

In writing not long ago about cowboy actor Randolph Scott's late-in-life career resurgence, I mentioned that he and Joel McCrea made one final Western together before retiring from the big screen. That's not strictly true, as McCrea did make a handful of other film appearances after 1962's "Ride the High Country," though neither the films or his turns in them were notable.

"Ride," which is also widely regarded as director Sam Peckinpah's first important film, is better described as the coda on McCrea's long, and largely unappreciated, career. It did in fact mark Scott's last time on the big screen.

A low-budget film that barely made a cultural ripple at the time of its release -- it was actually the bottom half of a double bill with the Viking actioner "The Tartars" -- "Ride" has continued to grow in estimation over the years to the point of being heralded by many as a major film the helps mark the close of Hollywood's Golden Age.

Set in the early years of the 20th century, the two actors play aged ex-lawmen yearning to recapture something of their glory days. Meeting by happenstance, they join forces to guard a shipment of gold dust from a mining town back to the city. Though they don't set out with the intention of the proverbial "one last job," it inevitably becomes that.

The amount they're to be entrusted with is initially described as a quarter of a million dollars, later amended to one-tenth that upon the signing of the contract with the bank, and finally just a hair over $11,000 when they actually take possession. This is significant to Steve Judd (McCrea) only as a matter of personal pride, a measure of how much credit is left in the reputation of a famous relic like himself.

The sum is more important for Gil Westrum (Scott), as he intends to steal the gold rather than turn it into the bank. He spends much of the movie trying to enlist Steve to join the scheme, indirectly through little hints and suggestions. But he's prepared to betray his friend if needs be. His hotheaded young sidekick, Heck Longtree (Ron Starr), serves as his backup and insurance.

During one of their conversations on the trail, Gil does succeed in getting Steve to admit that if men like themselves were justly compensated for their work, he figures he would be due $1,000 for every time he's been shot. (Paying out four times, in his case). Instead, Steve has little to show beyond a decent horse, a fancy gun rig and frayed shirt cuffs.

For their trouble, the three men are being paid $40 a day -- half for Steve, $10 each for his two recruits -- which works out to a little more than $1,000 in today's dollars. So the temptation to steal $250,000, or even $11,000, is enormous.

Steve had spent the previous years working in brothels and bars, while Gil sunk even lower, portraying himself as "the Oklahoma kid," a fictional notorious gunman at carnivals and such. Wearing a fake mustache and ostentatious outfit, he bets rubberneckers 10 cents apiece that he can outshoot them at a game of spinning targets. Even then he has to rig the odds, loading his pistol with buckshot cartridges to ensure a hit.

Along the way to Coarse Gold, the squalid little mining town, they pick up a straggler in Elsa (Mariette Hartley), a young girl who lives alone with her fire-and-brimstone father (R. G. Armstrong). She can't stand the lonely life and her father's abuse, so she sneaks off to join the strangers.

She's clearly attracted to Heck, and vice-versa, but when he nearly forces himself upon her -- only being pulled off by the two older men -- Elsa resolves to continue her original plan of marrying Billy Hammond (James Drury), a man she courted who joined the gold rush.

Unfortunately, Billy has four brothers, and it soon becomes apparent that the Hammonds have a rather... socialist view when it comes to marriage and sexual relations. As in, "share and share alike." Billy seems unbothered by this, so long as he gets first dibs on Elsa's favors.

Needless to say, she's not enamored of the notion of becoming the family sex slave. The marriage goes through in a rambunctious, whiskey-soaked ceremony at the Coarse Gold saloon, but Gil, Steve and Heck rescue Elsa from the Hammonds' clutches. An inquest is called, and Gil threatens the town judge (Edgar Buchanan) to testify that he's not legally empowered to perform weddings. They make off with Elsa, leading to a fatal showdown with the Hammond boys.

The Hammonds make quite an impression as villains, combining a level of genuine malevolence with bumpkin-esque comedic relief. That's helped by the presence of Peckinpah favorite Warren Oates as Henry, the dimmest of the bunch. Oates furrows his brows in a vain attempt to understand basic societal conventions like taking baths or not shtupping your sister-in-law. And, for some strange reason, birds are attracted to Henry, constantly flocking about him or even perching on his shoulder.

The other brothers are Elder (John Anderson), whose name spells out his role; barely-past-boyhood Jimmy (John Davis Chandler); and stoic Sylvus, played by quintessential "that guy" actor L. Q. Jones.

Interesting aside on Jones: his given name was Justus E. McQueen, but in his first movie, "Battle Cry," he was cast as a character named L. Q. Jones, and he liked the moniker so much he used it the rest of his career, which included a lot of Peckinpah films. Another one for the May Wynn files.

I enjoyed "Ride the High Country," though it's hard to argue it up further than being a well-done B-movie Western oater. The central dynamic is Scott and McCrea as hard men who've absorbed a lifetime of being downtrodden and disregarded. Regret is at the core of every scene in the movie, such as when Gil inquires after Steve's one-time, long-ago chance at love and family.

They both still look the part of genuine cowboys, though McCrea sports a bit of a paunch, and his grey hairs are carefully combed over the thin spots. He carries himself with a sense of both shame and pride, mournful for past misdeeds -- including a stint on the wrong side of the law -- while retaining his certainty that it's not usually hard to tell right from wrong.

Scott's character is a little underdeveloped by comparison, failing to struggle much with any kind of moral quandary about stealing the gold. It's only after Steve catches them in the act that Gil seems to have a moment of self-reflection and doubt.

As with most of Peckinpah's work, the women don't fare so well. Elsa comes across as a naive temptress, repeatedly presenting herself to men for their attention and then becoming defensive when they respond too enthusiastically. Given today's watershed moment of awareness about sexual harassment and abuse, her repeated rape peril is titanically disturbing.

Although N. B. Stone Jr., is credited with the screenplay, according to most lore Peckinpah himself and William S. Roberts actually wrote it.

Though I think it's a trifle overrated, "Ride the High Country" is still a worthy conveyance for two Western stars to ride off into their well-deserved sunset.