The Burton Binge: "Sleepy Hollow"

Each Sunday with “The Burton Binge,” Sam Watermeier will look back at one of Tim Burton’s films, ultimately tracing the return to the auteur’s roots with the October 5 release of “Frankenweenie,” an animated adaptation of Burton’s first live-action short film.

This week, Sam is joined by Nile Arena to discuss Burton’s adaptation of Washington Irving’s legendary short story about a village terrorized by a headless horseman. Unlike the film’s bumbling detective, Arena is well-versed in the ways of the macabre. In addition to being a featured author in the book “Horror 101,” he is probably the staunchest defender of what is largely a forgotten film in Burton’s oeuvre.

Sam: The best place to start is at the beginning. I'd like to talk about our first experiences with “Sleepy Hollow.” I remember its release being a big deal, marking the first time I'd seen a Tim Burton film in the theater — from beginning to end, at least; I snuck into the second half of “Mars Attacks!” It was also his first hard-R film. (“Ed Wood” doesn't count; it acquired that rating with a few measly F-bombs. But perhaps it only seemed like a hard R at the time; keep in mind I was only 8 years old. In actuality, the film often spews blood with tongue planted firmly in cheek. In 1999, on the eve of the millennium and the sobering horror films of the Aughts, “Sleepy Hollow” arrived like one last vintage campfire yarn told in good fun. I realize that only in hindsight, of course. What was your perspective on it when it was released?

Nile: “Sleepy Hollow” was a pop cultural force even before I sat down and saw the movie. Like you, it was the first Burton movie I saw in the theater — and certainly the first “horror” film I saw on the big screen, unless you count “Casper.”

I saw the film’s Topps trading cards in a comic book store in Cleveland sometime in the fall. The package just had a two-color image of a headless horseman by a giant spooky tree. I was 11, and I loved everything related to Halloween, so I bought a pack of the trading cards, not really knowing if they were from a movie or a comic book or what. The first picture on one of the cards I saw was Christopher Walken with a cape and sharpened teeth. I knew who Walken was thanks to “SNL” and “Batman Returns,” so that was a huge incentive to see the movie. But I don't know if it was completely clear that it was a film that hadn't come out yet. Trading cards seemed to come out for any number of old movies, so I don't think it even occurred to me this could be a new movie.

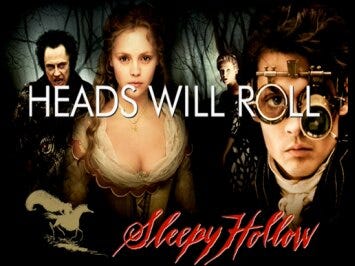

Then the marketing really kicked into high gear. I remember seeing Christina Ricci on the cover of Rolling Stone (and on "The Daily Show"; I had a big old crush on her) and posters with the tagline “Heads Will Roll.” The TV spot showed Richard Griffiths' death scene heavily. I ended up seeing it right when it came out. I don't know if it was opening night, but it was the first weekend. I covered my eyes during Martin Landau's beheading at the beginning, but I think it clicked midway through that it was going to be a detective story and I relaxed quite a bit.

I think that first time viewing it I was a little let down that Young Masbath, Ichabod Crane and Katrina survive. I think I told my mom it would have been better if one of them had died to make it more dramatic. Bear in mind, I'd just finished a community theatre run of Shaw's “Caesar & Cleopatra,” so I had a lot to say about tragedy.

It's interesting you mention the rating business. You know, I see the “Ed Wood” R-rating differently. Sometimes a film holds a higher rating largely because its tone would be completely uninteresting to the teen/tween market for whom the PG-13 rating was created. Films that have no hope of crossover appeal tend to lean toward a restricted zone simply to spare themselves the pretense of being top earners. (“A Serious Man” comes to mind as a pretty recent example.)

The studio behind “Wood,” Touchstone Pictures, was (is?) a Disney subsidiary that also released “Rushmore” without any post-production interference or power in the editing room. And “Ed Wood” is probably the only Burton movie, at least from his salad days, that left final cut in the hands of the filmmakers. The morphine subplot would never have made it into a lower-rated film, nor would the treatment of transvestism or Bill Murray's equally comic and touching sex change woes. This was 1994, when gay characters were stuck as either silly friends or dying of AIDS in mainstream Hollywood if they were even seen at all.

If anything, it's a softer R rating with “Sleepy Hollow.” For all its gore and menace, it's a fairly chaste love story, if we momentarily discount Miranda Richardson's brief humping of the swollen, pinkish Jeffery Jones.

Sam: It's funny that you mention the avoidance of mainstream success because that is precisely what Burton seemed to be trying to attain after “Sleepy Hollow.” However, unlike “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” and “Alice in Wonderland,” “Sleepy Hollow” doesn't seem like a mere, easy exploitation of a story similar to his own work. It represents a crossroads in his career — a point in which he strapped into his comfort zone but still did interesting, inventive stuff within it. What's funny is that all of his films are about outsiders yet they don't work when Burton is an outsider to the story's world as well. Take “Planet of the Apes,” for instance. The world of “Sleepy Hollow” is an obvious place for Burton to visit yet he makes the trip worthwhile. How do you think he does so?

Nile: The outsider issue has been discussed from the earliest days of Burton's career, and I think it has remained valid even as his films have begun to feel like exercises in pure style. It strikes me as similar to detractors of Wes Anderson and even the Coens in that once critics have decided they “understand” a director's oeuvre, any further work within their established style is a slight to its audience. I don't tend to agree with this route of criticism, which owes a debt to that turd scribbler Pauline Kael (and Ebert, the Paul to her misguided Nazarene) more than anyone, but in Burton's case, I think theirs is a legitimate beef.

I think “Sleepy Hollow” works above all because of its sincerity. It played by its own set of bizarre rules while still blowing up a windmill and having a chase sequence on horseback. But even the chase inverts a lot of expectations, from how often Johnny Depp's Crane is legitimately terrified to the gallows-humor clumsiness of the headless Hessian rider. Its baroque set reminds the enlightened of Hammer studios' use of fog and Grand Guignol set dressings rather than any semblance of realism. Where Burton failed with “Apes,” and even as I see it with “Big Fish,” is that he set out to dress the world within the expectations of a teenager in Skokie. No matter how darkly lit the world of the “Apes” is or how many circus big tops are in “Big Fish,” it is still very much a world with which we as viewers are familiar. Then it becomes Burton's job to fill in the rest with characters, almost archetypes usually, and the tableaux feels more like a puppet show than a story that might take you somewhere unexpected.

The criticism of “Alice in Wonderland” as the primrose path of least resistance for a director like Burton is accurate. But it isn't only because the visuals and characters seem tailor-made for his style. I think “Sleepy Hollow” also owes a debt to its screenplay, which shifts the focus from the absurdity of Ichabod Crane to the grotesque of colonial America. It becomes a whodunit with Richard E. Grant's Withnail for an inspector and the assorted corrupt players from a Hawthorne novel as the suspects. The absence of Johnny Depp hidden under a prosthetic nose and large ears with a screechy voice is also welcome and, frankly, surprising given the image of the schoolmaster Crane's appearance and Depp's obstinate glee to hide his good looks.

There is still Hollywood business, with Ricci's mooning over Depp and the haunted past of Ichabod's mother, but I think even that comes as a surprise and plays into America's ugly past of persecuting women as witches when there was any threat to conform. Thank heavens they didn't give Christina Ricci magical powers, right?

Sam: Hopefully you’ve made people want to revisit the film. I know I do! But I, too, have always thought “Sleepy Hollow” is unfairly regarded as the beginning of the end for Burton. It’s probably his best genre experiment since “Batman,” a big Hollywood film that still feels personal to the director behind it. Unfortunately, Burton followed it with a rather bad genre work that I will discuss next week. Stay tuned!