The Hands of Orlac (1924)

I don't review a lot of silent films here in this space — and by "not a lot," I mean I believe this is the very first one.

I freely admit I don't respond to most silent film like I do other classical cinema. To me, it's almost an entirely different art form. Silent films are, with some exceptions, much more theatrical and slow-paced. They were made for people used to stage productions, vaudeville or crushingly long novels.

Let's face it: People just had more patience a century ago. Of course, they had to; there just wasn't as much to do.

One advantage silent films had was their universality. By changing around the title cards for dialogue, a film could just as easily play in Istanbul as Idaho. Music was also much more important to a movie, since it consisted of the entire auditory aspect of a cinematic experience (and often was played live by an orchestra).

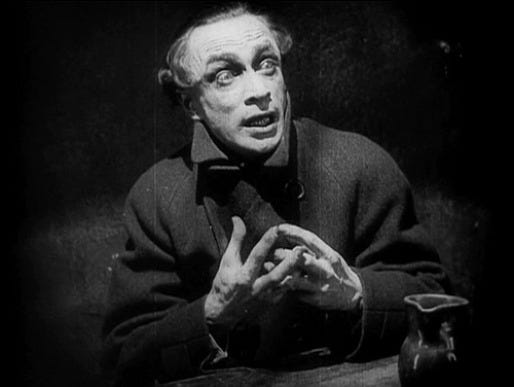

"The Hands of Orlac" is pretty typical of its era. It falls into the expressionist horror neighborhood, and is a fairly close cousin to the better-known "The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari," which also was directed by Robert Wiene and starred Conrad Veidt. Veidt is most remembered as the stern German commandant from "Casablanca," but in his youth made a career out of playing spindly fellows given to violence and/or supernatural control.

(He also starred in 1928's "The Man Who Laughed," as a man whose face was frozen in a rictus grin, and clearly served as the inspiration for the Joker character.)

Based on a story by Maurice Renard, "Orlac" tells the tale of a famous pianist who loses his hands in a train accident, and wakes up to discover that doctors have miraculously stitched on a new pair that work perfectly. (Except for playing the piano.) Alas, they turn out to have belonged to a condemned murderer named Vassuer. Haunted by the origins of his appendages, Orlac begins to have visions and feels compelled to knife somebody — particularly his wife, Yvonne (Alexandra Sorina).

Later, he's bedeviled by a man (Fritz Kortner) with iron gloves who claims to be the guillotined murderer, brought back to life by the same mysterious medical process that returned Orlac's hands. He murders Orlac's father and demands a large chunk of the inheritance as compensation for his stolen hands.

Story-wise, there isn't that much to tell... actually, I just relayed the entire plot to you. As I said, the narratives of silent films tend to be fairly simplistic.

The movie is very slow-moving, with long extended scenes of Veidt staring at his hands as if they were foreign objects, and bulging his eyes out in that way very popular in films of the time to depict people in peril or physical distress. (Sorina also gets to pull this move several times.)

The visuals are creepy and evocative, but my modern sensibility kept wishing the director would speed things along. My reaction was very much the same as that I had watching Terence Malick's "The Thin Red Line" — it really doesn't take long to convey emotional power through moving imagery. When you keep the camera focused on the same thing, on and on, or keep cutting back to the same image, over and over, you're beating a dead horse, cinematically.

It's a beautiful-looking film, even with the graininess and scratches that come with 90-year-old celluloid. The use of irises and slow fade-ins and -outs feels very dated, of course, but Wiene's use of dense, murky shadows offset by harshly lit foregrounds and faces is still compelling to look at.

This idea of body parts imbued with their own spirits became a familiar one in movies after this one came out. "The Hands of Orlac" was adapted into film twice more, and a 1980s horror flick starring Michael Caine, "The Hand," which scared the bejeezus out of me when I was a lad staying up too late watching HBO, also seems clearly inspired by it.

The metaphysics remain pretty vague. At first we are told Orlac's new appendages act independently of his will; he finds he can no longer play the piano, and even his handwriting resembles Vassuer's. Subsequent events, though, suggest it's all part of an elaborate delusion contacted inside his fevered head.

I enjoyed the artistry of "The Hands of Orlac," but it exists for me now as an artifact rather than a living, breathing piece of cinema. Watching it is akin to wandering through a museum, peering at dusty trophies behind thick glass. We relate to these objects not for the power they hold, but their echo.

3.5 Yaps