The Last Rodeo

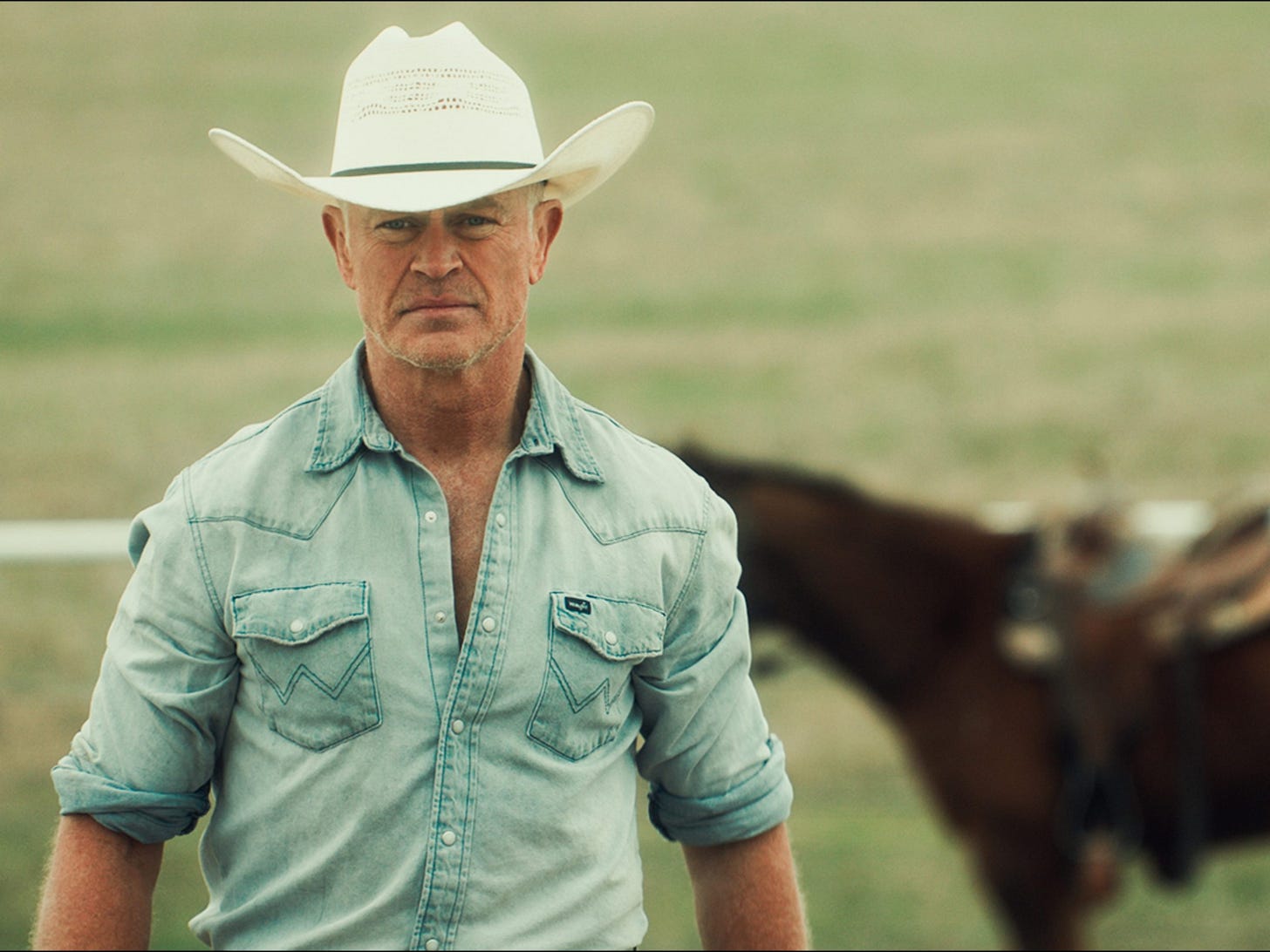

In this sturdy modern Western with a faith-based bent, Neal McDonough plays an over-the-hill bull rider who attempts a comeback to raise money for his grandson's medical care.

Neal McDonough has one of the great faces of modern cinema, the sort of canvas he can paint with all sorts of colors. He can be scary as hell in a villain role, which he did a lot of for awhile. More recently as he’s gotten older, he’s slid into more stolid, comforting parts as hard men testing their mettle with unexpected challenges.

He’s also become a mainstay of faith-based films, especially Angel Studios. A few months back he starred in “Homestead,” an apocalyptic tale, and now he’s back in “The Last Rodeo,” a sturdy Western in which he plays an over-the-hill bull rider attempting a comeback to pay for his grandson’s medical bills.

Thematically it’s a cousin to “The Rookie,” with Dennis Quaid as a middle-aged baseball pitcher. Getting back in the game is not something the protagonist does for himself — he’s not chasing faded glory or an ego boost — but on behalf of youngsters who look up to him.

Directed by veteran filmmaker Jon Avnet (“Fried Green Tomatoes”) from a screenplay he cowrote with McDonough and Derek Presley, it’s a formulaic but effective picture. McDonough gives a sterling performance as Joe Wainright, a classic tough cowboy who’s afraid to show weakness, but he’ll do anything for those he loves.

Along the way, he’s also the target of some light proselytizing by Charlie (Mykelti Williamson), an old but estranged friend, a former rider and bull wrestler who counsels Joe to set aside his anger, with an occasional Bible quotation here and there.

“You got to stop being so mad at Him up there. Because He's given you more than most,” Charlie says, in his own particular way in which he can seem comforting and antagonizing at the same time.

The setup is that Joe was a major star of the Professional Bull Riders (PBR) league back in his day. It’s a brutal sport marked by serious bodily injuries and not infrequent deaths, and most men retire by their mid-30s. Joe went into a tailspin after his wife died, got on a bull while drunk and broke his neck.

He’s been out of the game for about 15 years now, doing a little farming and horseshoeing on his modest spread in Edna, Texas. He dotes on his grandson, Cody (Graham Harvey), who aims to follow in his footsteps, but not without major objections from his mom, Sal (Sarah Jones).

Sal and Joe have a scratchy daughter/father relationship. She spent years helping Joe get healthy and sober again, pushing the pause button on many of her own dreams like becoming a large animal veterinarian. She doesn’t exactly resent Joe for this, but his taciturn roughneck routine certainly doesn’t make for a lot of overt demonstrations of warm gratitude.

So when Cody is diagnosed with a difficult brain tumor — the same kind that took Joe’s wife, to boot — Joe and Sal find themselves at loggerheads about how to handle it. On top of that, their insurance will not cover all of the surgery costs and they’re on the hook for six figures they don’t have.

Without consulting anybody, Joe resolves to take up an offer from the PBR chief, Jimmy Mack (Christopher McDonald), to ride again on their Legends tour, competing against modern-day bull riders like current champ Billy Hamilton, a cocky little bantam rooster played by Daylon Swearingen. The top prize is a million bucks.

You can probably guess how this plays out: funny bits where some young girls dismiss Joe as a potential rider; goofing from the younger riders that gradually morphs into open hostility; scoffing from the media and announcers, until… Joe surprises everybody — including himself — and turns out to be a legit contender.

Despite the predictability of the plot, the movie plays out with surprising emotional heft and an unerring feel for the material. It understands what a film like this is and what it’s trying to do, and does it well.

It’s a nice-looking picture (cinematography by Denis Lenoir) with a very authentic production design and feel. Like Joe, still tied to a rotary phone on the wall of his ranch house. Or his early-90s Ford king cab “dually” truck, which he’s still nursing along with STP and TLC.

McDonough strips his shirt off for a couple of thirsty locker room scenes, demonstrating that at near 60 he’s still doing the work.

Williamson hits some solid notes as a guy who was probably a lot like Joe, but managed to move on and open himself up. There’s a wonderful moment where Charlie lays into Joe in a diner about how he shut him out right when a friend was what he most needed. He stomps off to the bathroom, then just lingers, the two men’s backs turned to each other, the harsh words reverberating inside each of them.

Most movies nowadays wouldn’t think to take that kind of pause — a few seconds of nothing that actually contains everything. Tip o’ the hat.

“The Last Rodeo” is a throwback bit of hearty filmmaking with a little God talk sprinkled in. It may not buck any conventions, but knows how to stay in the slot.