The Mule

Clint Eastwood actor/director-vehicle The Mule is an imperfect, unambitious, sometimes confused movie that seems mostly to be about remembering what's important in life, and the perils of failing to do so, though similarly to how The Wolf of Wall Street did, it seems to paint its protagonist's runaway lifestyle as an entertaining, worthwhile substitute for a more virtuous one. That said, The Mule is fun enough in its own right, and boasts its share of uniquely framed emotional moments. Awards committees will rightfully pass on this one in most (if not all) categories, but just because it isn't getting nominations doesn't mean it isn't effective cinema.

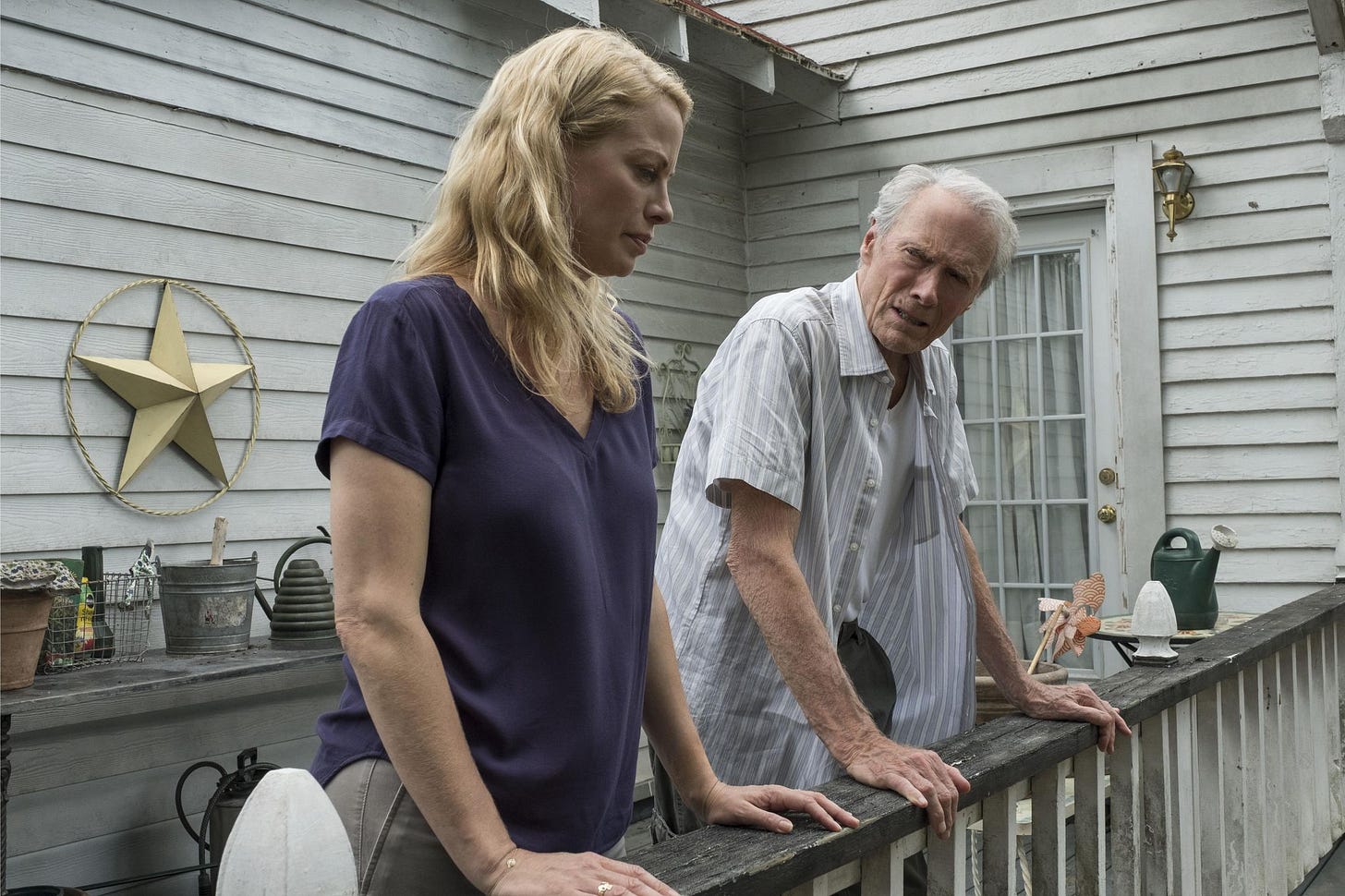

The Mule tells the story (based on real New York Times article "The Sinaloa Cartel's 90-Year-Old Drug Mule" by Sam Dolnik) of elderly horticulturist Earl Stone, who up to the point at which our story begins, has spent most of his life favoring work over family, opting to spend 60 hours a week on the road exhibiting his flowers at conventions for decades on end rather than being around for his wife and children. Earl missed his daughter's wedding, graduation, most birthdays, and ignored most of his wedding anniversaries. When we meet Earl, he is all but excommunicated from the rest of the family, his one advocate being his granddaughter GInny (Taissa Farmiga). When Earl's flower business goes kaput, because "the Internet ruins everything," (actual line) Earl is offered a job driving for a Mexican drug cartel. Of course, he doesn't realize what he's transporting at first, but even after quickly becoming aware, it's hard to turn down the huge sums of money he's being paid for every road trip. Meanwhile at the DEA, special agents Bates and Trevino (Bradley Cooper and Michael Peña) are being pressured to come up with some major busts, or else find a new place of operation.

It's a pretty straightforward, innocent story, and I think that's what allows the film to work as well as it does. As can be expected from an Eastwood film, there are moments of awkwardly inserted social commentary, including topics such as the generation gap, smartphone addiction, racial tension, and police brutality, though most are touched on so gingerly it's hard to tell where Eastwood stands on them, or whether or not he really understands them to begin with. Several of these moments are played out in the form of comedy, which teeters between clever satire and problematic ignorance. The less loaded comedy in the film works much more effectively; Earl is a wisecracking, hard-nose sonofabitch who, while not exactly a great family man, is weirdly lovable in his crotchetiness.

How other characters fare varies throughout the film. Eastwood seems to take a moment to bond Earl with every major character, though often it's just these singular moments that are passed off as actual relationships and character development. They are certainly emotionally effective scenes in and of themselves, held together by potent dialogue and convincing, understated performances from the ensemble cast—but even then, it's hard to sell genuine growth or change in a character or between two characters, when it's essentially all reduced to one scene. The Mule would rather show us the strange, exciting, dangerous, and funny life of a geriatric drug trafficker than spend time gradually building up the characters' relationships to others.

In the end, it's hard not to get the feeling that The Mule wanted to be a much more important, substantial statement on something, it's just not entirely clear what, and it isn't as resonant as it seems to think it is. That said, it is thoroughly enjoyable to watch how this unique caper plays out, and the cast's performances elevate each scene to being better than they have to be. The Mule isn't a must-see before awards season, but if you like this kind of "stranger than fiction" truish story, check it out at a matinee; you won't be mad you did.