The Panic in Needle Park (1971)

"You rat up, you don't rat down." --Detective Hotchner

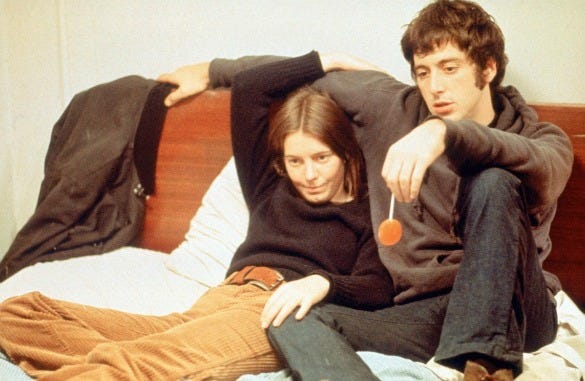

"The Panic in Needle Park" was Al Pacino's second official screen role, but the first one of any consequence. It's mostly remembered today for that reason, though his co-star, Kitty Winn, actually won the Best Actress award at the Cannes festival in her own first starring role. But her career faded pretty quickly after this and the "Exorcist" films, and she retired from screening acting in 1978.

It's a pretty staggering performance by Pacino, his screen presence already fully formed and filled with that agitated vigor that would become his hallmark. His Bobby, a low-level street hustler and drug dealer, is a charming sweetheart when there's plenty of heroin to be had, but a manipulative lout when there's a panic — aka an extended period of short supply.

Decades before "Kids" or "Trainspotting," "Panic" offered a grisly glimpse of drug-addicted youths hanging around Sherman Square Park, a meager finger of vegetation crammed along Broadway on the Upper West Side of New York City. The film was considered very shocking for its day — it was even banned in several countries — and is believed to be the first mainstream movie that depicted people injecting themselves with needles.

The nomenclature is a bit dated, as you might expect. Sleeping with someone is "making it" or, in more negative connotations, "balling." Users refer to their product, mostly heroin, as "junk." Or they just use vague references to available quantity: "Got any?" or "I need some." Though they are hesitant to refer to themselves as "junkies," preferring to say they're "chipping" — using because they want to, not because they need to.

In their universal delusion, everyone is "chipping," especially Bobby and his new old lady.

Seen today, it's an episodic film that rambles through the highs and lows of the junkie lifestyle without a particularly cohesive narrative. It follows the perspective of Helen (Winn), a nice girl from Fort Wayne, Ind., who gradually dissolves into the counterculture, moving downward in association from artists to street scamps to whacked-out users, eventually becoming a prostitute and dealer herself.

Her lowest point, not actually depicted in the movie, is when she sells pills conned out of a doctor to some kids, and is arrested by "Hotch," aka Detective Hotchner (Alan Vint). The local "narco" cop, Hotch wears a leather jacket and long hair, drives around in a beat-up VW Bug and has more or less made Needle Park, aka Sherman Square, his own stomping grounds.

Hotch knows all the junkies, coexists with them on a largely peaceful basis of shared enmity, occasionally busting one of them and using them as leverage against their fellows. There's not much animosity among the ostensible friends, who understand the game and realize there are times they will be ratted out, just as there are times they will be the rat. Occasionally someone disappears from the park for awhile, then turns up again a few months later after their stint in jail is up.

As long as there is heroin and needles to be shared, this squalid form of friendship abides.

Richard Bright, best known as the enforcer Al Neri from the "Godfather" films, turns up as Hank, Bobby's older brother. He's a career criminal himself, but carries himself around wearing suits and a superior smirk. He's chipping too, but doesn't sully himself with handling the junk, sticking to burglaries of high-end apartments.

Hank will clear $600 in a single night (about $3,700 in today's dollars) and brags that he's never been caught, because he breaks toothpicks in the door lock in case the owners come home while he's burglarizing, and he can hop out the fire escape. He tries to help Bobby by bringing him in as a partner, but Bobby overdoses on the night of the job. They try again the next day, but a cop wanders into the alley and Bobby is sent off to the hoosegow for a few months.

During the break, Helen sleeps with Hank to keep her supply of dope rolling. Initially resistant to using, especially after seeing how Bobby turns into an inert zombie while high, she soon becomes a serious addict.

Both Pacino and Winn do impressive jobs playing high, wandering between euphoria and paranoia, with every stop in between. In one of the most memorable scenes, they decide to shoot up in the men's room of the Long Island ferry after buying a puppy on a whim. "I don't wanna be up while you're coming down!" Bobby snarls. He makes her put the whining pup outside the door, which quickly scampers off the edge of the deck and is lost in the swirling drink.

Other notable actors making early stops in their career are Raul Julia and Paul Sorvino. Julia plays Marco, the uncaring artist who got Helen pregnant, forcing her to undergo an unsafe and unsanitary abortion in the film's opening sequence. Bobby, turning up at Marco's studio to sell junk, takes pity on her and treats her kindly. That leads to them hooking up when Marco decamps to Mexico.

Sorvino's part is much smaller, as an agitated john of Helen's during her prostitution phase, who presses charges when she steals $75 out of his wallet.

"Panic" had an interesting genesis. It started out as a photographic essay of real junkies in Sherman Square published in serial form by Life magazine in 1965 by James Mills, who later turned it into a fictionalized novel. Husband-and-wife writing team Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne ("A Star Is Born") wrote the screenplay after John's brother optioned the rights.

Director Jerry Schatzberg had only made one other film following his own career in photojournalism, and would go on to direct a number of other notable films, including "Honeysuckle Rose" and "Street Smart," which launched Morgan Freeman's career.

Schatzberg goes for a very spare cinema verite style that works well with the film's sober, intimate tone. He even chose to throw out the entire musical score composed by Ned Rorem, relying on street sounds and chatter to from the movie's acoustic background.

"The Panic in Needle Park" isn't a great film in of itself, but it is a notable one worth revisiting. In addition to launching the career of Pacino and a bunch of other people, it depicted without varnish the toll hard drugs exact upon the flesh — and the souls — of people who think poison can replace what's missing.