The Truman Show (1998)

There are literally college courses taught about "The Truman Show," which is not something most pop-culture movies can say for themselves. People have made allusions to its alleged deeper meanings via Christian, urban-planning, political and psychological interpretations. I generally find that sort of analysis a waste of time, though the film's insights on the insidious power of media are hard to deny.

Consider that, coming out in 1998, "The Truman Show" predated most of the reality TV crazy, with the exception of MTV's "Real World" and a few other shows. Ron Howard would, a year later, try a similar theme with "Edtv" starring Matthew McConaughey. I don't think it's an insult to note that movie is barely remembered at all.

Though it's important to emphasize that while "Edtv" and all reality shows are about people who proactively decide to have their activities taped — an arrangement that attracts a certain type of personality — "Truman" is the only creative production I can think of in which the main character — and only he — is unaware of the fact that his doings are being viewed.

In addition, Truman Burbank also believes that his tiny hometown island of Seahaven is real, when in fact it is all an elaborate facsimile — a TV set the same size and economic impact of a small nation. This basic premise, of our hero living in a constructed world inside of the real one, in which he becomes the main focus of audiences both helpful and antagonistic, would be repeated in a science-fiction version in the following year's "The Matrix."

"Truman" even presages the only recently realized phenomenon of the "reality talk show," in which programmers create an additional (and revenue-generating) venue for people to chat about the main show. The movie's "TruTalk," hosted by Harry Shearer, is the forbear to today's "The Talking Dead."

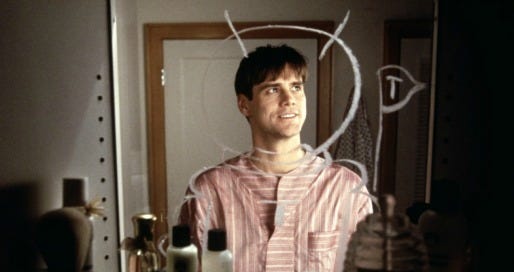

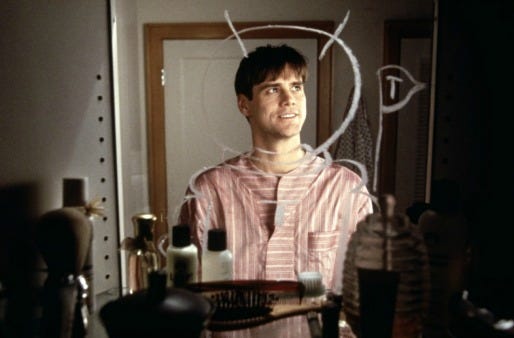

"Truman" also marked the delineation of Jim Carrey's career shift from straight-out funnyman to more dour, ambitious projects, especially "Man on the Moon" a year later. His career has bobbled and wobbled since then, though the recent "Dumb and Dumber To" announced his full retreat back into the comedy safe zone.

Though I usually have difficult naming my all-time favorite films, I have no such reservation about citing directors I most admire. And Peter Weir would certainly be on that list (plus the likes of Ridley Scott, John Boorman, George Miller and David Lean ... apparently I only go for Brits and Aussies.)

Along with "The Truman Show," Weir has "Gallipoli," "Witness," "Green Card," "Picnic at Hanging Rock," "The Year of Living Dangerously," "Fearless," "Dead Poets Society" and "Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World" to his name.

Not a bad cinematic epitaph, that.

(Though personally I hope Weir, who recently turned 70, stays with us a very long time and, Sidney Lumet-like, continues cranking out amazing films right up until the grave beckons.)

Of course, the premise of "The Truman Show" is absurd. It's preposterous to think that you could raise a man to the age of 30 without him ever realizing that everyone around him is actors pretending to be his neighbors, friends — even his mother and father. And that the perfectly tidy town, with its cotton-candy coloring and eternal sunshine (actually Seaside, Fla.), is not real. Plus the treacherous legal and moral implications — Truman is essentially an imprisoned slave, owned by a corporation.

But Weir and screenwriter Andrew Niccol (an accomplished director himself of films like "Gattaca") cleverly delay the big reveal of what's really going on until about one-third of the way into the movie, so the audience never really questions the conceit. By then Truman has become so known and endearing to them, they don't even have to suspend their disbelief.

As the tale opens Truman is starting to grow antsy, shucking off the "script" of a perfect life that producer/eye in the sky Christof (Ed Harris) has constructed for him. Though married to incessantly upbeat Meryl (Laura Linney), he still pines for Sylvia (Natascha McElhone), a background character who caught his eye and found herself ditching the rules to be with him.

Of course, whenever something happens to break through this "fourth wall," the show has a small army of burly men to rush in to block Truman's view and clean things up. Over the years various saboteurs have attempted to breach the show's sanctum by parachuting into Main Street or holding up signs saying "It's a show!" But Truman has remained blessedly indifferent.

(Though, now that I think about it, I'm not sure if this really constitutes breaking the fourth wall, which is supposed to exist between an ongoing work of art and its audience. In this case, it is not the creative act that is disrupted by acknowledging itself, but internal sabotage by unwilling participants. Someone needs to come up with a name for that.)

I was surprised watching the movie again (for I think the first time in 16 years) how weak Truman's relationships are with the actors playing his mother and father. They only really get one substantial scene apiece, and dad's is when he is reintegrated into the show after his supposed death when Truman was a boy. (This was a calculated psychological manipulation by Christof to render him afraid of water and thus unlikely to want to leave his water-bound hometown.)

Even his relationship with Meryl goes relatively unexplored, or the morality of how the actors who have spent their life participating in the charade feel about it. Only Marlon (Noah Emmerich), who plays his best friend, appears to hold any genuine affection for Truman. Though he carries out Christof's orders, he often seems on the verge of blurting out the truth.

The character of Truman remains something of a goofy cipher, a mix of Carrey's manic early stand-up comic persona and the script's plot demands. In "Ace Ventura" and a lot of Carrey's other early movies, there was an overt aspect of "performance" to the characters, of them playing a part in order to carry out the intended comedic effect, and I think we see a lot of that in Truman. Even he thinks he's putting on a front.

His interactions with other Seahaven residents, often repetitive from day to day, are boring even to Truman. So he's more apt to notice little screw-ups like accidentally receiving the radio signals of the crew tracking his movements via his car radio, or a set light falling from the sky. Indeed, one of the subtlest of subsidiary themes is the notion that, after three decades on the air, the puppeteers pulling the strings have gotten distracted and careless.

Thought-provoking and eerily prescient, "The Truman Show" will likely be one of those films that withstands the tests of the ages — at least, until we've all got cameras sewn into our bodies, and everything everyone does is recorded and transmitted, everywhere. Say, 2030?