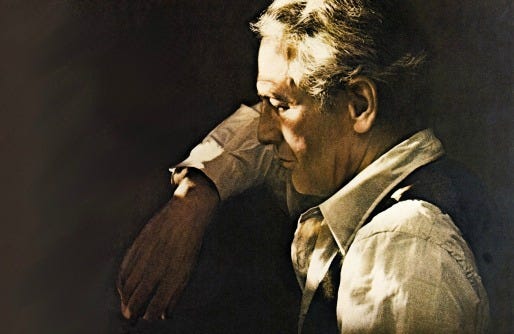

The Verdict (1982)

If there's a greater actor in a better role than Paul Newman in "The Verdict," I haven't met it.

This 1982 legal drama directed by Sidney Lumet is one of my cinematic touchstones, a film that grabbed me at an early age and profoundly affected the way I approached movies. It still retains a strong hold on me and I think about it often, even though I doubt I've seen it more than a total of three times.

Watching it as a precocious preteen bedazzled by Jedis and replicants, "The Verdict" opened me up to a universe of serious films where the characters didn't do much more than talk. It's an incredibly spare film, lacking big showy moments, and with barely any music to push or pull the audience into easy emotional catharsis.

Even Frank Galvin's courtroom speeches are rambling and unfocused — he comes across less as an attorney presenting a compelling legal argument than a stumblebum hanging out on the corner lamenting the woes of the world to no one in particular. It's hardly the fiery "you're out of order!" brimstone you usually see.

To call Frank down on his luck would be to presume that he ever had any.

When we first meet him, Lumet and screenwriter David Mamet (on just his second screenplay) go out of their way to depict him as a lowlife ambulance-chaser. He plays pinball with grim concentration, taking a breakfast of a beer with a raw egg cracked into it before heading out on his daily rounds. This mostly consists of following the funeral notices in the paper for potential cases. He bribes the morticians to introduce him to the bereaved family as an old friend so he can slip them his card and drum up a wrongful death lawsuit.

We learn he's only handled four cases over the last three years, all of them out-of-court settlements, and that Frank had a brush with the law, nearly losing his law license for jury tampering a decade ago. Since then, he's been riding the downward spiral, with retired lawyer friend Mickey Morrissey (Jack Warden) throwing him a case from time to time and peeling him off his office floor when Frank's been on one of his benders.

The latest is a good one, a real "money-maker," Mickey promises. But Frank can't even remember the case when Mickey brings it up, 10 days before trial. He pulls himself together enough to meet with the clients, the sister and brother-in-law (Roxanne Hart and James Handy) of a woman who fell into a coma after going to the hospital to give birth and being given the wrong anesthetic. (Interestingly, the film never mentions what happened to the baby.)

The hospital is owned by the Archdiocese of Boston, and the calculating-but-not-uncaring Bishop (Edward Binns) offers Frank a $210,000 settlement. For his standard one-third fee, that would garner him a neat $70,000 (about $170k in today's dollars) — enough to keep Frank flush in cheap cigarettes and breath spray for years. But he refuses, and insists on taking the case to trial.

Why? Part of the film's greatness is never definitively answering this question. Clearly Frank is deeply impacted when he visits the woman in the hospital, curled up in a permanent fetal position, and takes Polaroid photos of her. Lumet cleverly doesn't allow his camera to show her from the same angles as Frank's pictures, which bring her sad plight into focus — for us and for him.

His clients don't want to go to trial. They make clear they're looking to recover $50,000, which is the amount a local facility wants as an endowment to take over perpetual care of the woman. The sister and brother-in-law want to move out west and wash their hands of the burden. So why does Frank turn down the settlement, nearly coming to blows with the sister's husband when he finds out?

From a legal standpoint, his case is a mess. He only has the testimony of one over-the-hill country doctor (Joe Seneca), who turns out to be black to top things off. It's funny and sad to think about how just three decades ago, having an African-American doctor as your star witness was seen as undermining the case.

Of course, Frank stumbles into luck with a last-minute witness, an admitting nurse who was bullied into changing the medical form to cover up the doctor's mistake (played by Lindsay Crouse, employing a full-on Boston blarney accent). He does so in part by breaking into a post office box to get an uncooperative woman's phone records.

Frank sees this as his last shot for ... well, not greatness, but at least legitimacy. After he wins this case, the final scene of him reposing in his office, refusing to answer a phone call he knows he oughtn't to, suggests Frank will resume practicing the law with something like resolve. He'll probably keep boozing, and handling lowlife cases, but he'll be an attorney again.

About that phone call. Charlotte Rampling plays Laura, a divorced woman who takes Frank up like a lost child off the street and becomes his lover/confessor, bucking him up when things look bad. Certainly it's not because a burned-out 55-year-old drunk has any business nabbing her interest. Even his initial come-on lacks embellishment: "My God, you are some beautiful woman."

Secretly, she's being paid off by Frank's opposing counsel, Ed Concannon (James Mason, in pure aristocratic arrogance mode), to feed him information. When Frank finds out, he belts her ... hard.

I'd like to talk about that punch. It was the thing I most remembered from seeing the movie, when Mr. Movie Star Paul Newman punches out a willowy-looking woman. There's a long, silent pause before he does so, as they look at each other. Wordlessly, the look of betrayal on his face is reflected in her own, as she realizes the gravity of what she's done.

The look on Newman's face is just classic. It's the expression of a beat-down dog who's just had his last bone taken away from him, and he's finally riled up and mad. He's ready to fight. Frank has lost everything — his status, his wife, his friends — and here is this woman gnawing away the last tatters of his dignity.

Violence against women is repugnant, but in the film's context it feels totally justified.

Aside from Newman, the performances are roundly solid. Rampling has a certain reserved, damaged quality; we later learn she used to be a lawyer herself and is looking to get back in the game. Concannon is the real twisted soul, taking a case he could easily win and putting a couple of fingers on the scales of justice. I wonder if it ever occurred to Concannon that he is engaging in the sort of activity that nearly cost Frank his law license.

Warden is his usual blowsy, hard-talking presence. Seneca has a quiet dignity as a man who earns most of his livelihood testifying against other doctors in court. He acknowledges his vocation but fervently affirms the validity of it. Wesley Addy also has a small, subtle role as the accused doctor.

Milo O'Shea, who recently passed, is just terrific as Judge Hoyle, who handles Frank like a wayward student hawking spitballs in the back of his classroom. In his heart of hearts, he'd rather just see Frank thrown out into the wilderness, but he does his duty anyway. Not without prejudice, however; it's quite clear that the judge favors the defendant and works to undermine Frank's case.

However, when the surprise witness has just depth-charged Concannon's case, he and the judge have this great exchange of stares where O'Shea peers out from beneath those marvelous caterpillar eyebrows with a look that says, "You're on your own, me bucko."

That's one of the things that dazzled me when I recently watched "The Verdict" again — how it makes every big moment bigger by going smaller. In its lean, small, often wordless and soundless way, "The Verdict" is a piece of true greatness.

5 Yaps