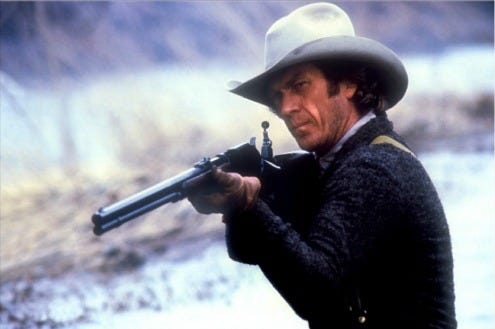

Tom Horn (1980)

There are the bones of a great story inside "Tom Horn," Steve McQueen's disappointing next-to-last film. But it's buried down deep in a desert of cinematic ineptitude, in between a TV hack of a director and a pair of screenwriters who seemed more motivated to deliver a star vehicle for McQueen than tell a gripping story.

McQueen was one of Hollywood's most iconic stars of the 1960s and '70s, but in his latter years he seemed to grow disinterested with moviemaking entirely. He retired, sort of, reappeared for the lure of big money for a cameo in "The Towering Inferno," made a couple of flicks nobody saw and was being offered ungodly sums for various big-budget projects, turning them all down. Then he quickly made his last two films, "Tom Horn" and "The Hunter," before dying in 1980 at age 50.

Having worked with some of Hollywood's greatest filmmakers, I can only guess why McQueen chose to have "Tom Horn" directed by William Wiard, a TV veteran with zero film credits before (or after) this movie. Script men Thomas McGuane and Bud Shrake similarly fail to acquit themselves with anymore more than ham-handed Western tropes and one of the most astonishingly unconvincing romances in cinematic history.

The film chronicles the last days of Tom Horn — a tracker, interpreter, ersatz lawman and assassin — with plenty of historical facts on its side.

Tom Horn was called the man who captured Geronimo, but the truth is a number of men helped bring in the legendary Indian chief, who ultimately surrendered himself after several fits and starts. Tom got involved in various scrapes between parties establishing the order of the dying Old West, as cattlemen who favored the free ranges butted up against the increasingly settled townships and farmlands.

As the movie opens, Tom is wandering without purpose. He gets into town and, while drinking a whiskey at the saloon, manages to insult boxer "Gentleman" Jim Corbett, getting his tail handed to him in the ensuing melee. Tom actually runs from the encounter, cementing his position as a man who never initiates violence even if he has spent his life putting an end to it, usually as the last one standing.

He's approached by John Coble, a member of the wealthy cattlemen's association played by the great character actor Richard Farnsworth. The association is tired of having its stock rustled and sold off and wants Tom to put an end to it. The hire him as a "cattle detective" to hunt down and deal with any rustlers — arrests if possible, but kills are preferred.

At first things go well, as Tom's hard-won prowess is too much for the rustlers. But the townsfolk quickly become horrified by his brutal but effective killing. After being attacked in town, Tom wounds his would-be assassin, then casually walks up to him lying on the ground and finishes him off with a rifle shot to the head. The association realizes this can only hurt its station and prospects.

This is where things go narratively askew. If the association wanted Horn gone, why didn't it simply pay him off and order him to move along? Given Tom's innate amiableness — despite his ruthlessness with a gun — it seems likely Coble could've convinced him to vamoose.

Instead, a local boy is shot under mysterious circumstances with a .45-60, the rare type of rifle used by Tom. Based upon only this happenstance and a conversation between Tom and the politically ambitious marshal, Joe Belle (Billy Green Bush), overheard by a local reporter, Tom is convicted and hanged.

The film is passable during the first hour or so, as a ham-handed, but often effective, contemplation on the dying of the frontier days. Tom says he does not fear death, but he is afraid of losing the ability to come and go as he pleases and live in the rough hills that are a home to him.

Once the trial starts, though, the film loses its way. Tom pays little attention to the proceedings, having daydreams about a romance with local teacher Gwendolene Kimmel (Linda Evans). I'm not exactly sure when this supposed relationship took place, since we never learn about it until after the time when it was supposed to have occurred has passed. It's possible that Tom's musing remembrances are merely a fantasy about the life he could have had.

In any case, the pairing is fleeting and bewildering. Gwendolene practically throws herself into the cowboy's arms then abruptly rejects him for his nomadic lifestyle.

Also less than completely realized is the character of Sam Creedmore, the salty old sheriff, played by Slim Pickens, recruited to capture and imprison Tom during his trial. They talk to each other as if they've been friends or at least colleagues all their lives, but nothing is indicated that they even met before. Maybe Tom should've been having flashbacks about his jailer instead of the school teacher.

McQueen's performance is perhaps the film's only saving grace. With his ambling walk, unembellished skill at killing and quick-patterned speech, McQueen draws a portrait of a man who refused to walk away from his fate even if he did not exactly embrace it. He was a certified minimalist as a performer, preferring to let actions and long glances take the place of big-scale emoting and loquacious dialogue.

I sometimes think McQueen would've been happier making movies in the silent era when talking was considered overrated. Look at "Le Mans," the racing movie in which I don't think McQueen utters a single word for the first 45 minutes.

2 Yaps