Trouble with the Curve

"Trouble with the Curve" exceeds the sum of its parts. An imperfect movie, it has modest flaws and inconsistencies that one can point to. But in the theater, with the light flickering, it all just works.

It's like a baseball pitcher who displays shaky form in his windup and delivery but hurls strike after strike. The fact that you recognize where it goes wrong only makes how everything ends up in the right place even more amazing.

You sit there, marveling.

This excellent drama stars Clint Eastwood in his most vulnerable performance ever and is easily one of the finest movies of 2012. It acts as a perfect counterpoint to last year's wonderful "Moneyball."

Both films are set in the world of baseball but are not really sports movies. Instead, they explore the mix of obsession and fear inside the players, the coaches and the scouts.

In "Moneyball," the heroes were the young nerds with their computers and cutting-edge statistical analysis, which allowed them to circumvent the hard-bitten experience of the old-timers. Here, the crotchety veteran scouts are the good guys, and the whippersnappers who stare at screens but never watch a game play the heavies.

Gus Lobel (Eastwood) is an aging scout for the Atlanta Braves, his specialty being snapping up young talent from the Carolinas. But it's been awhile since he recruited any big names, and his eyesight is starting to go. Gus has been a widower a long time and an ornery cuss even longer, so it's no surprise that he keeps his macular degeneration a secret.

Perhaps his only friend in the world is the head of scouting, Pete Klein (John Goodman, in a solid, comfortable performance). He senses something is wrong and convinces Gus' daughter, Mickey (Amy Adams), to go be with her dad on his big trip. Gus has been given a make-or-break assignment, to judge whether a beefy young swatter named Bo Gentry (Joe Massingill) is the real deal and should be taken with the Braves' first-round pick.

Mickey and her dad are hardly close, and if he's a piece of work, she's studying to outdo him. A lawyer who hasn't taken a Saturday off in seven years, she has a boyfriend dropping hints about marriage but treats his overtures like a scheduling conflict.

Mickey has a big case looming that will determine whether she makes partner at her firm. Spending a week trying to reconnect with her standoffish father, and serve as his eyes at games, is not high on her list. The dutiful child, she goes anyway.

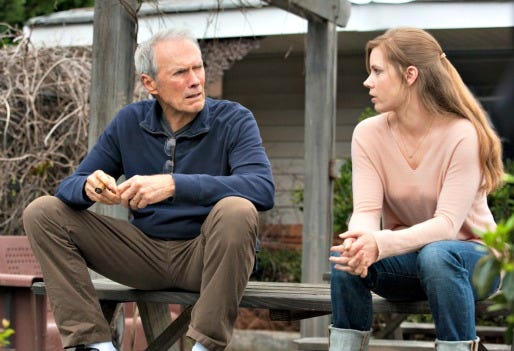

It's in plumbing this tenuous relationship between father and daughter that the movie saves its best pitches. Adams and Eastwood have an easy, organic connection, which is a hard thing when playing characters divided by a lifelong inability to see eye-to-eye.

Playing the third wheel is Justin Timberlake as Johnny Flanagan, a former pitching ace signed by Gus who blew out his arm and is now working his way up the food chain with the Red Sox, doing some scouting while hoping to break in as an announcer.

Johnny and Mickey share a timid, funny little courtship — two lost souls feeling each other out, natural enemies who can't help bantering. For awhile, the movie shifts almost entirely away from Gus and onto them, and we don't mind because it feels so natural.

Timberlake has a tendency to be glib and superficial in his performances, oft skating by as the fast-talking charmer, but here he gets a chance to show a few deeper notes and doesn't falter. As an actor, he's getting there.

The real revelation, though, is Eastwood. At age 82, he does things he simply couldn't have done 25 years ago, balancing moments of humor or tragedy on a risky edge. At one point, he sings sweetly to his wife's gravestone, and in another he rejects his daughter's heartfelt outreach.

Given the sorts of movies he used to make and the way he played them, the old Eastwood would have just landed on these moments, hit them solidly and moved on. Here, he caresses and elevates them, like a jazz musician holding a long note, bending it and adding colors unwritten on any sheet of music.

The last time Eastwood acted in a movie he didn't direct himself was 1993's "In the Line of Fire" for veteran Wolfgang Petersen. Here he's doing it for a rookie screenwriter, Randy Brown, and first-time director Robert Lorenz, who's been a producer/assistant director on a number of Eastwood projects.

It says something when someone of Eastwood's stature entrusts himself to a creative team who are novices. From the bracing success of "Trouble with the Curve," it would seem he shares Gus' knack for spotting new talent.

4.5 Yaps