Who the *$&% Is Jackson Pollock? (2006)

I had not intended to write about "Who the *$&% Is Jackson Pollock?", a 2006 documentary that was to be one of the pitifully few movies experienced for pure pleasure. But I found the doc, about a retired truck driver who claims to have bought a genuine Jackson Pollock painting for $5 at a thrift story, too stimulating to ignore.

In the end, it's less interesting to me as a story about whether the painting is genuine than about the clashing of the art world against other segments of culture it deems unworthy of sharing its company. In the end, one is uncertain about whether Teri Horton's painting was made by Pollock, famous for his seemingly random paint drippings. But you can be sure that the curators, collectors and critics who are at the heart of the insular art community desperately need for it to be a fake.

Why? Simply because, having denied the authenticity of the work for over a decade, it would be mortifying to admit they were wrong. Over and over they insist that Pollock paintings don't just pop up out of nowhere. Their argument essentially seems to be, "There's no way that painting could be real because if it was, we would have known about it already."

Never mind that Pollock was a mercurial artist, one who faced lifelong problems with alcohol and mental instability, was known to give away his paintings to friends and visitors and throw finished works he wasn't satisfied with in the trash.

One genuine Pollock was saved from a local dump near his studio only because a businessman decided the back of it would make for a good sign in the window of his store. Is that tale really more outrageous than an elderly trucker discovering one in a thrift store?

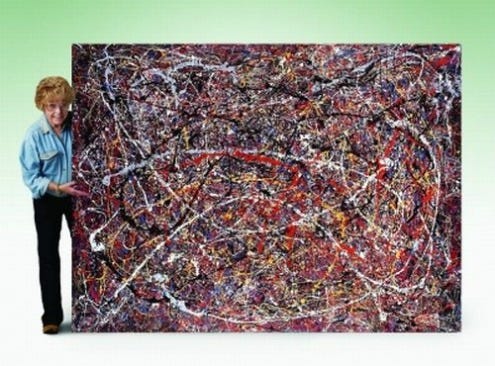

Certainly, the piece appears to be in Pollock's distinctive style — a mesmerizing swirl of colors and shapes with no form other than one the viewer chooses to impose. A close friend of his thinks it might be genuine. Other experts are doubtful.

Their skepticism is based on two factors: provenance and connoisseurship, two things vital to the judgment of works of art and antiquities and both as ephemeral as the mist. Provenance simply means the ability to track possession of a painting from an artist to the present. By having a solid chain of custody, it helps prove a work of art is by the artist in question.

But provenance is easily faked. Even Thomas Hoving, the legendary former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, admits that the provenance for many acknowledged works of great art are known to be false.

But because Teri lacks anything beyond a receipt from a now-defunct thrift store, her provenance is lacking. After years of being ignored, Teri invents a wild story about the painting being created during a wild weekend Pollock spent partying with Hollywood stars, which finally convinces some art experts to look at it.

It's total bullshit, she happily admits, but it's telling that it required a BS tale to pique their interest. A faked provenance is better than the absence of one.

As to connoisseurship, this is essentially a word to codify the arrogance and exclusionary nature of the big-money art community. "We are the experts," they tell the world, "and our expertise trumps any other evidence."

No doubt Teri herself clashed with their definition of an art collector. Stubbornly blue-collar, with plain speech decorated liberally with obscenities and insults, Teri's idea of culture is hanging out with her friends at the VFW with a row of whiskey shots in front of them. At 73, she's had a long, tough life, and it becomes clear in writer/director Harry Moses' portrait that the battle against the art snobs has become the sole reason she carries on.

The title comes from Teri's self-reported statement of what she said when a high school art teacher told her it might be a Pollock. The fact that she bought it only as a lark gift for a friend, who refused it but suggested they use it to throw darts at, helps certify Teri's "country bumpkin" bona fides.

Teri insists over and over it isn't about the money, it's about having her painting recognized. But she's clearly fibbing or self-deluded. As the documentary reveals, at two separate times she was made large offers for its purchase, for $2 million and later for $9 million. But because someone once told her Jackson Pollock paintings sell for $50 million and up, she refuses to part with it for a penny less than this figure.

Perhaps she refuses to undersell what she thinks it is worth because doing so would mean it is anything less than 100 percent genuine.

Teri also doesn't help herself with sometimes erratic behavior — such as hiring to represent her in the sale one Tod Volpe, a former art dealer to the Hollywood glitterati who went to jail for fraud. Volpe's crimes involved taking money for works that were not delivered, not misrepresenting fake art as genuine. But Volpe still has the mood and manner of a huckster, and no doubt Hoving and his crowd turned up their noses a notch higher when they found out he was repping Teri.

The latter part of the film explores forensic evidence supporting the painting's authenticity. Peter Paul Biro, a European forensic expert, is brought in and finds a fingerprint on the back of the painting. He compares this to another fingerprint on an acknowledged Pollock and finds a match. Then he travels to Pollock's barn studio, preserved as a museum right down to the actual paint cans and brushes he used, and finds another fingerprint that matches the first two. A footnote states that after filming concluded, a fourth fingerprint on a genuine Pollock painting also matched.

The experts protest that Teri's painting contains acrylic paint, which they insist Pollock never used. But Biro scrapes up paint samples from the spattered floor of Pollock's studio and finds acrylic.

It's funny to watch the connoisseurs struggle to invalidate this evidence. They sputter dismissively about crime-scene techniques being brought to bear in the world of painting and sculpture. They continue to cling to their illusory staples of provenance and connoisseurship rather than hard facts.

Finally, one of the art experts makes a telling admission. When you're dealing with pieces of art worth tens of millions, or even hundreds of millions of dollars, it becomes a big business deal rather than a pure appreciation of art for its own sake. In these sorts of high-stakes games, investors are notoriously risk-averse. They want a sure thing; otherwise, they're not going to put their money down on the table.

So a painting with a lot of evidence to support its authenticity is rejected as too risky because the art experts are not willing to give their stamp of approval. After so many years of denying not just the painting but Teri Horton herself, the connoisseurs find their reputations are at stake.

Real or fake? Genuine or inauthentic? Is it Teri, or those who would deny her and her painting, that is obscuring the truth?

4 Yaps