You Only Live Twenty-Thrice: "Diamonds Are Forever"

“You Only Live Twenty-Thrice” is a look back at the James Bond films.

Each Friday until the release of the 23rd official Bond film, “Skyfall,” we will revisit its 22 official predecessors from start to finish, with a bonus post for the unofficial films in which James Bond also appears.

Even today, the clatter and clang of casinos summons big-name entertainers like a siren — enticed by fat paydays to set up temporary (or semi-permanent) residency in Las Vegas and pack in the tourists with a predictable greatest-hits revue.

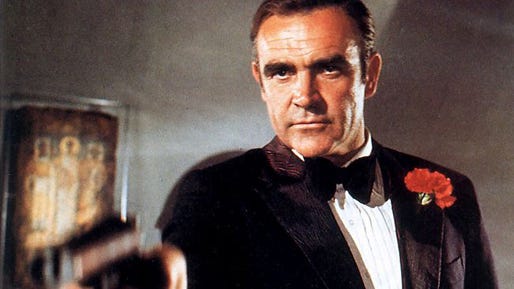

Sean Connery wasn’t lured to Vegas for his one-liners or showtunes, but he took a then-record salary to reprise the role of James Bond there one last time. It’s too bad that the resultant effort, 1971’s “Diamonds Are Forever,” feels less like a triumphant return and more like a cheesed-up cabaret caricature of Bond.

“Diamonds” is easily the most intentionally amusing Bond film, with as many sly laughs as groaners. (That’s the creeping influence of co-writer Tom Mankiewicz, who rewrote almost the entirety of the original script in an enticement to bring Connery back and drove most of Roger Moore’s movies toward a far lighter, winking tone.) Murderous lackeys Mr. Kidd and Mr. Wint have a most interesting subtext. Plus, this beefy Mustang chase through the center of Vegas is smash-up fun ... and check out Connery's awesome dismount at the start of the clip.

Aside from that, though, “Diamonds” has a surprising dearth of action sequences — as if Connery wanted all the spoils and none of the spills. Its finale is essentially a more poorly filmed, seaborne version of the climactic assault in “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service” and the eventual nuclear explosion effects are … well … this.

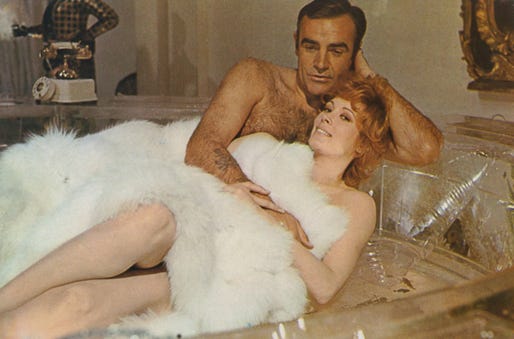

And although he was barely 40 when “Diamonds” was filmed, Connery seemed to have aged considerably. His attention also seems arrested by Sin City’s distracting sensory overload and unfocused on reviving the charm, confidence and conviction that made Bond so great.

Today, “Diamonds” retains interest less as Connery’s grand finale — you’re honestly better off to remember “You Only Live Twice” as his swan song — and more as the birth of Bond into the more free-spirited 1970s. There’s regularly peppered profanity, a glimpse of an erect nipple (on a dead woman, no less) and a flash of Connery’s own hairy haunches. “Diamonds” opened up Bond’s world — and Connery’s bank account — in big ways, but it’s a disappointingly small-time effort.

Before Connery signed, it was anyone’s guess which actor would assume the role of 007. That’s because George Lazenby bowed out after “Service,” following his agent’s foolish notion that the Me Decade would make Bond a musty curio.

Moore had finally ended his run on “The Saint” … only to begin production on another TV series — the short-lived “The Persuaders!,” co-starring Tony Curtis and overseen by “Service” director Peter R. Hunt. Michael Gambon, who would later replace Richard Harris as Dumbledore in the Harry Potter films, said no thanks. And Timothy Dalton, courted after Connery’s departure in 1967, was still awfully young.

And while it might seem silly to woo Americans for a part so unmistakably British, remember whose bacon Bond had saved for the last eight years. Former Batman Adam West was considered as was a 34-year-old Burt Reynolds.

Enter John Gavin, a half-Mexican heartthrob who starred alongside Doris Day, Sophia Loren, Susan Hayward and Sandra Dee but had also worked with heavyweight directors like Douglas Sirk, Alfred Hitchcock and Stanley Kubrick. Gavin was signed and set to inherit the franchise … until David Picker intervened.

As the studio chief of United Artists, Picker was adamant about working with producers Harry Saltzman and Albert R. “Cubby” Broccoli to retain rights to release the Bond films. And in lieu of a truly can’t-miss replacement, he wanted Connery back at any cost.

He got him for a cool $1.25 million, which Connery donated to the Scottish Education Trust — a charity he founded for Scottish artists to apply for funding without having to leave the country to pursue their careers. Charitable inclination aside, it’s hard to see that as anything but a swipe of animosity at the relentless American studio-system pace of his first five Bond films.

But that was just for starters.

Connery got $10,000 for each week “Diamonds” ran over schedule (as he knew many Bond films did). United Artists also agreed to fund two films of Connery’s choosing. One was Sidney Lumet’s “The Offence,” in which Connery played a homicidal cop undone by fantasies of rape and murder. And, most lucratively, Connery earned a percentage of the film’s $116 million gross.

On a side note: Gavin’s contract was also honored. But he would be burned by Bond once more. After he was also signed for “Live and Let Die,” producers’ insistence on an Englishman in saw Gavin bombed out again and Moore inserted in his place.

So, United Artists had its iconic star again. “Goldfinger” director Guy Hamilton was returned to the fray. Shirley Bassey came back to belt out another brassy title theme. Naturally, it’s wise to base the plot on one of the producers’ goofy dreams, right?

Albert R. “Cubby” Broccoli insisted on a story inspired by his dream — one in which Bond was captured by a man pretending to be Howard Hughes, the mentally addled magnate who also happened to be Broccoli’s friend.

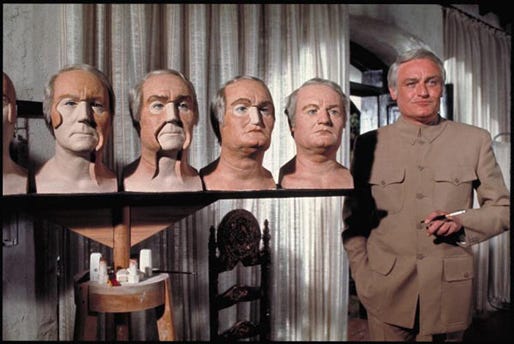

Thus, Blofeld is back as a main protagonist for a third straight film, with another new face and a … full head of hair? The not-at-all-bald Charles Gray plays Blofeld in a turn more forgettable than formidable that requires him to don drag to escape.

“Diamonds” begins as if “Twice” has just ended and “Service” never even happened. Bond throws a scalawag through a Japanese shoji screen, demanding to know Blofeld’s whereabouts. He eventually finds Blofeld prepping for plastic surgery in a moist cave system and drowns him in a boiling, bubbling mud bath.

Cue Blofeld’s mewling white cat and a title sequence that superimposes lots of diamonds in obvious naughty places. As Bond title sequences go, it’s unremarkable, but the slippery drumbeat propels Bassey’s hypnotic vocals with a touch of funk.

Seemingly victorious in his ongoing battle with Blofeld, Bond accepts his next mission, investigating a price-fixing scheme involving South African diamonds. The trail will first lead him to the Amsterdam apartment of diamond smuggler Tiffany Case (a dismally ditzy Jill St. John) — where he engages in a pale imitation of the flush-faced fight in “From Russia with Love” — and eventually to Vegas, where a bevy of duplicitous smugglers awaits them both.

Hamilton awkwardly cuts back and forth between Bond’s initial debriefing and the introduction of the film’s two most intriguing characters — Mr. Kidd (Bruce Glover, Crispin’s dad) and Mr. Wint (Putter Smith, better known as a jazz bassist).

Kidd looks like Wink Martindale’s bumpkin cousin. Wint resembles Rowlf from “The Muppets.” Eventually, we learn they’re working for Blofeld. But the script quickly suggests a history of sadism independent of this caper, as well as a long, twisted and, more than likely, romantic relationship. One of them refers to Tiffany as quite attractive “for a lady.” And here’s how they commemorate homicide and helicopter detonation.

No one would ever accuse a Bond film of progressive sexual politics, let alone progressive homosexual politics. And, as suggested more latently by Elsa Klebb in “Russia,” these are not the first foes he’s faced who seem to have a same-sex preference. But neither Bond nor the script mocks or vilifies them because of their orientation. 007 simply matches wits with them in a scene that, admittedly, ends as goofily as it possibly can.

If nothing else, Bond’s treatment of Kidd and Wint as equal-opportunity villains suggests a slight social expansion of the character’s, and the films’, worldview. Whether it would take a step back with the blaxploitation-inspired “Live and Let Die” is up for discussion next week.

Besides, the freer thinking suggestive of the 1970s is far more compelling than the cotton-candy color scheme that runs rampant in the casinos or moments of camp that include slot-pulling elephants, POV shots of high divers and a sideshow attraction where a woman is “turned into a gorilla.”

There’s also a daffy escape in a lunar rover, introduced as either a way to capitalize on moon-landing excitement from two years earlier or cleverly tip hats to those who believed it to be a hoax.

And then there’s Bambi and Thumper, who issue what is unquestionably the most violent Connery beat down since Oddjob.

That’s where the Hughes figure enters this Bond story — in the form of an enigmatic billionaire named Willard Whyte (singer / sausage-maker Jimmy Dean), whom Bambi and Thumper have held captive under orders from Blofeld.

It seems Blofeld, and his identical double, have vocally impersonated Whyte — who hasn’t been seen in years — from a penthouse perch high above the Vegas streets. (As Bond ascends a skyscraper to reach the suite, Hamilton uses Vegas’s glittery galaxy to mask the usually laughable rear-projection effect.)

Blofeld isn’t trying to manipulate the diamond market. You guessed it. He’s up to no good in outer space again, building a diamond-powered laser to instigate nuclear panic from above. Blofeld’s plot a lazy retread, and so is the siege on his oilrig — the most anticlimactic final Bond battle yet. Reportedly much grander in its original concept, Bond and Blofeld were to duke it out mid-air and into a salt mine. When the salt mine owners denied permission, the sequence was shortened … and weakened.

In all, it’s a fairly sad sendoff for the man whose face instantaneously flickers to mind as James Bond. In this case, the appeal of “Diamonds” is fleeting. But in the clarity and cut of “Dr. No,” “Russia,” “Goldfinger” and “Twice,” Connery’s Bond will sparkle forever.

Next week: “Live and Let Die”

BULLET POINTS

Early versions of the script used Auric Goldfinger’s twin brother as the villain, and Gert Frobe was actually courted to return. Then producer Albert R. “Cubby” Broccoli had his dream about Howard Hughes, and the story was radically retooled.

The infamously reclusive Hughes owned what was then the Las Vegas International. Filmmakers sought to use the hotel as his onscreen doppelganger Willard Whyte’s casino, the Whyte House. Instead of accepting payment for filming on his property, Hughes, a Bond fan, asked for a 16mm print of the finished film.

In the scene when Bond recognizes diamond smuggler Shady Tree in a Vegas entertainment magazine, Sammy Davis Jr. can be seen on an adjacent page. Davis Jr. filmed a cameo in which he recognized James Bond, but the scene was left on the cutting-room floor.

“Diamonds Are Forever” is the last official Bond film to majorly feature either SPECTRE or its nefarious head, Ernst Stavro Blofeld. After this, courts upheld Kevin McClory’s legal claim that he, and not Ian Fleming, created SPECTRE when Fleming, McClory and Jack Whittingham unsuccessfully tried to write a Bond screenplay.

In a classic pot-kettle-black moment, producer Harry Saltzman allegedly sought to deep-six Shirley Bassey’s title theme because he hated its sexual innuendo. Sample lyrics: “They are all I need to please me / They can stimulate and tease me … Hold one up and then caress it / Touch it, stroke it and undress it / I can see every part.” Composer and conductor John Barry would later reveal in an interview that he told Bassey to imagine she was singing about a penis.