You Only Live Twenty-Thrice: "Die Another Day"

“You Only Live Twenty-Thrice” is a look back at the James Bond films.

Each Friday until the release of the 23rd official Bond film, “Skyfall,” we will revisit its 22 official predecessors from start to finish, with a bonus post for the unofficial films in which James Bond also appears.

Mindless, joyless, stale, dumb, meandering, indistinguishable. The “Batman and Robin” of the Bond series. Save for that last knock, these are some of the kinder descriptions critics concocted for “Die Another Day.” At best among the big-time Bond-movie list-makers, it’s the fifth most awful of them all. At worst? Well ...

Without question, “Die Another Day” is a rocket ride that ultimately blasts through the stratosphere of craziness to test the very threshold of coherence — even more so than “Moonraker.” But unlike Roger Moore’s folly, “Day” is unequivocally awesome. As Bond rankings go, Top-10 kind of awesome.

“Day” ably lifts graphic-novel weight in Act One before expertly tossing it aside for airy, comic-book gleefulness. It’s even got an outlandishly grotesque villain: Zao (Rick Yune), a bad, bald albino with translucent eyes, DNA permanently stuck between Asian and Caucasian and diamonds lodged in his cheeks. (Although not the big bad, Zao is a Duracell thug Renard should’ve been in “The World is Not Enough.”)

Calling “Day” over the top suggests limits to its lunacy that don’t exist. A DNA replacement therapy on a remote Cuban island. Bionic super-suits. 007 essentially outrunning the sun. But these excesses embrace everything that’s exotic and electrifying about 007 — the sex more vivid, the betrayals more blindsiding, the twists more hairpin, the villains more unhinged. It’s as close a cousin to “You Only Live Twice” there’s been. But dumb “Day” is not — a trippy pulp rendering of the canon’s longstanding ideas of duplicity and identity.

For what may turn out to be the last time given the Daniel Craig direction, the series hearkens back to the gadget-driven, gee-whiz what-ifs of its 1960s roots, abetted by a budget almost five times that entire decade of Bond. And this high-speed ascent into G-force levels of absurdity mirrors its climactic action sequence: The vehicle may flirt with structural collapse, but it lands, amazingly and dazzlingly.

Even the “James Bond Theme” almost breaks apart here under composer David Arnold’s slippery techno break-beats in the iconic gun-barrel sequence.

But there’s nothing else bright and shiny about “Day’s” first 30 minutes — which begin with Bond surreptitiously surfing the gray, Communist coastlines of North Korea. He’s there to infiltrate the military base of the Harvard- and Oxford-educated Colonel Tan-Sun Moon (Will Yun Lee), who’s trading African blood diamonds for high-tech hovercrafts to navigate minefields. (Even the first-act levity is brutal: We meet Moon walloping a punching bag inside which his anger-management therapist is trapped.)

After an unknown mole informs Zao, the Colonel’s right-hand man, of 007’s true credentials, Bond detonates his booby-trapped briefcase in desperation. His decoy diamonds are embedded in Zao’s face, and 007 gives chase to the fleeing Moon. Sports cars explode and hovercrafts spiral end over end. But there’s no self-congratulatory swagger to this pre-credits sequence. That’s because at the moment when it would otherwise end glibly, it darkens with defeat: Bond is captured by Moon’s father, a general, and becomes a thoroughly well-tortured prisoner of war.

“Day” also has the most sinister opening-credits of all — using CG to explain and enhance the narrative. Pinpricks of light explode like pain in Bond’s nerve endings with every sucker punch. Smoldering coals lack flame but sear Bond’s flesh with heat. And then there are scorpions, with whose venom Bond is repeatedly infected.

You could almost consider them visual hallucinations into which Bond must retreat if he is to withstand the assault. Given the unpredictably jittery schisms and percussive stomps of Madonna’s title song — like a toreador dancing on Bond’s sanity — throw auditory delusions in there, too.

Although oft derided, Madonna’s song is expertly produced and integrated into the story. (It makes up for her stiff, uncredited cameo as a fencing instructor cum exposition machine.) As with Garbage’s “The World is Not Enough,” the lyrics are cleverly interwoven into a character’s emotions (here Bond himself):

“I’m gonna destroy my ego I’m gonna suspend my senses I’m gonna delay my pleasure I’m gonna close my body now”

(Madonna’s video is also yet another of her eye-openers, with Madge filling in for 007 during reenactments of “Day’s” torture and fencing-fight scenes. What begins as stylish cross-promotion turns graphic when Madonna slices open her stomach and just gets weirder from there.)

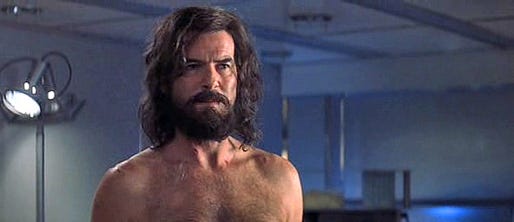

Then, the real shocker of “Day’s” first act: Bond has been there 14 months, disavowed by MI6 over five seasons of sustained suffering. And no Bond prior to Pierce Brosnan could pull off bearded and bedraggled so masterfully. All that saves Bond is General Moon’s lament for his late son: The General thought Western education would help his son build a bridge to geopolitical civility. Instead, it corrupted him absolutely, and he agrees to exchange Bond for Zao — now an anarchic terrorist whom MI6 has captured — in hopes he’ll flush out the Colonel’s collaborator — likely the same man who burned Bond.

Smooth sailing, right? Keep calm and carry on while fleshing out a traitor? Not so fast. M (Judi Dench) is convinced Britain gave up too much in exchange for Bond. And she fears this sentimentality may cost them handsomely in the long run. Not only is Bond’s licence to kill revoked (again), but this time it’s his freedom when he’s medically quarantined.

You could count on one hand the Bond films that face the character to confront an ultimate fear: That he would find love only to lose it in “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.” That his defense mechanisms would be stripped bare in “GoldenEye.” That he may not be the committed, collective agent he thinks he is in “Casino Royale” (2006). If only briefly, “Day” joins them: Here, MI6 has finally found Bond to be useless chaff.

So, how do writers Robert Wade and Neal Purvis tackle Bond’s anxiety? Here’s where the comic book kicks in. He simply escapes by, uh, faking cardiac arrest. Just like that, we’re in the creamy, rich center of a vintage 007 adventure, surrounded by the hard shell of a lively thriller about revoked-license vindication and vengeance. When 007 tells the hotel clerk “I’m just … surviving,” it’s more than a quip. It’s a mantra for a man whose own makers have stripped him of his relevancy.

Bond’s investigation leads to Cuba, where the brass has a smoky, spicy Cuban flavor and Arnold twists the “James Bond Theme” into the seductive sway of the nation’s son music style. What better place to pick up stogies again, right, as well as other smokin’ creature comforts?

Down to the knife strapped to her hips, Halle Berry is a darker-skinned doppelganger of “Dr. No’s” Honey Ryder — similarly birthed from the sea as lust incarnate. Giacinta “Jinx” Johnson is the name of this NSA agent, who quickly sees through Bond’s ornithologist cover. And “Day” has no reservations about giving Berry her second sex scene in as many years — albeit in a role as far removed from Academy Award consideration as it gets — that feels as much like an exorcism of pain as an expression of pleasure.

Bond has never been a sexual camel, so it’s no surprise that he thrusts, scratches and claws at Jinx like a starving wildebeest. And Jinx reciprocates the intensity with thrusting that takes Grace Jones’ grinds in “A View to a Kill” much further.

Berry is easily the actress with the most fame coming into a Bond-girl role. The “X-Men” films showed she could acquit herself well with sassy backtalk and blockbuster fights, as she does here. (She spits a couple of good defiant zingers at Bond’s “friend with the expensive acne,” and, for a time, there was talk of a spinoff series with Jinx.) But “Monster’s Ball” let Berry flex dramatic muscles her audiences didn’t know she had. Why not give her even the briefest amount of pillow talk in which she and Bond could confront emotional turmoil as explicitly as their sex?

Bond and Jinx eventually team up to take down Gustav Graves, a self-aggrandizing British diamond maven who has exploded onto the global market with lavish wealth in a matter of months. About 14 months, to be precise. It isn’t just a Union Jack parachute that makes Graves yet another distorted reflection of our hero. And just as you finger Graves for the mole, Purvis and Wade throw in a head-spinning, out-there twist.

Graves is actually Colonel Moon, and the insomniac side effects of altering his DNA have only elevated his adrenaline. It’s a brave and crazy variation on a modern Bond idea: What if we mistake today’s enemy for tomorrow’s friend only because he looks exactly like us?

Through the glowing, cybernetic tangle of wires in the eerie “Dream Machine,” Graves biometrically mimics an hour of slumber every day. It’s just one of several simulation touchstones in the script (both 007 and Moneypenny engage in virtual-reality environments), with which Purvis and Wade have more fun than in any of their other four Bond films.

As Graves, Stephens looks like Hugh Grant’s homicidal twin, dandy but deadly. And this particular Bond villain’s brand of rage is pure and uncut. A beefy, blocky slab of man, Graves challenges 007 to a fencing match that morphs from a ginger, gentleman’s game to a brutal, life-and-death broadsword battle. It’s a high-intensity modern brawl that still pays homage to the sheer high camp of the escalating situation.

As a man who must live out his dreams, Graves has gussied up a nightmare under the guise of global improvement. His satellite — aptly named Icarus, as Graves flies too close to the sun with his father’s wings — purports to harness the sun’s power and funnel it toward the globe’s darkest corners for crop development. What he really wants to do is carve up the Korean DMZ, take back South Korea by force and, with his unstoppable weapon, the world.

It would seem Bond has another ally — Miranda Frost (Rosamund Pike), an MI6 cryptologist undercover as Graves’ publicist. “Sex for dinner, death for breakfast” is how this icy, bookish spy describes Bond although she, unsurprisingly, eventually warms to his charms.

“Day” force-feeds plenty of eye candy — especially once Bond, Jinx, Frost, Graves and Zao converge on an Icelandic ice palace housing what Auric Goldfinger’s laser might look like in the 21st century. (This extravagant, otherworldly and practically built location that recalls the gloriously labyrinthine ’60s lairs of production designer Ken Adam.) So much that we give very little thought that Moon’s mole might not have been a man, and Frost’s betrayal stings with shock more than Elektra’s in “World.” After all, in a movie clearly giving anything a shot, why does there have to be an evil Bond girl?

Here’s where most people seem to bail on “Day” altogether — its moment of horrible, terrible, no-good, very-bad CGI. Bond escapes in dramatic fashion, hijacking Graves’s rocket car. It’s an inspired way to avoid incineration from the oncoming Icarus ray, but the way he dodges an avalanche is … well, far less visually impressive.

At the time, it was easily the most inexcusably bush-league CG effect in a blockbuster since the plane crash at the finale of “Air Force One.” But — but — “Day” pulls many “buts” from its lowest points — is it any less outlandish than the conveniently placed jetpack in the almost much-more beloved “Thunderball”?

Bond then doubles back to rescue Jinx using “the Vanish” — all the self-driving power of the 1997 and 1999 Aston Martins with more of the … invisibility? In interviews, producer Barbara Broccoli seems ashamed of “the Vanish,” like atonement was made through the skinflint gadgetry of “Royale.” After 20 movies, there’s no reason to be ashamed of giving Bond the most wonderful toys.

If anything, “Day” doesn’t use this pinnacle of anything-goes gadgetry enough. Perhaps Aston Martin, one of 20 companies paying a rumored $100 million total for product placement, limited overuse of a car no one could see. At least they get their money’s worth as Bond and Zao automotively duke it out in luxury cars empowered with small-arms fire.

That’s not even the final gambit of goofiness. Graves and Frost take Icarus to the air, where Graves reunites with ol’ pop in the futile hope of making him proud. It’s an odd pause for patricide that’s nevertheless powerful — even if it is like watching Joaquin Phoenix in “Gladiator” were he wearing a bionic suit that could deliver 100,000 volts of electricity.

Naturally, Bond and Jinx have given chase, and they separate to handle business with their respective foes. Frost’s sports-bra attire for a knife duel with Jinx seems an obvious stretch for exposed flesh, but really, it’s indicative of the hubris with which Graves has infected her. And as for Graves, well, all the diamonds in the world won’t help you if you let someone else pull your parachute on a depressurized plane.

Broccoli unfairly poo-poos the movie, but she’s right about one thing: There was absolutely no choice but to dial it down to a grounded reality in the next installment whether they moved forward with Brosnan or someone else. But that’s not because “Die Another Day” is an abomination of which to be ashamed. It’s because, alongside “Twice,” it’s peak Bond at its most aggressively outlandish and shamelessly entertaining.

Next week: ”Casino Royale” (2006)

BULLET POINTS

In ways overt and obscure, “Die Another Day” references each of the 20 preceding 007 films. There are common casting circumstances (Madonna appearing in the film, albeit not in the opening credits, as Sheena Easton did in “For Your Eyes Only”). Bond revisits old haunts in Cuba a la "GoldenEye," albeit under more ultimately pleasurable conditions. Past titles are name-checked in the script (“Diamonds are forever,” Graves says.) And during the Q briefing, gadgets from "Thunderball," “Octopussy,” "A View to a Kill," “From Russia with Love” and “Licence to Kill” can be seen in the background.

Halle Berry is the only actress to play a Bond girl after nabbing an Academy Award. But it didn’t help her luck on set. Debris from a smoke grenade entered her eye during an action sequence, and a half-hour operation was required to remove it. And while filming a hot sex scene, she began to choke on a fig, prompting Pierce Brosnan to administer the Heimlich Maneuver.

As for that sex scene, it originally had an additional few seconds in heaven, with Berry moaning loudly. The MPAA ordered them trimmed in order to preserve the PG-13 rating.

The British Airways flight attendant who serves 007 his martini is played by Roger Moore’s daughter, Deborah. She went on to appear in HBO’s “Rome” and the BBC’s “Sherlock.”

“Die Another Day’s” premiere was only the second at which Queen Elizabeth II was in attendance. The first was “You Only Live Twice,” 35 years earlier.