You Only Live Twenty-Thrice: "GoldenEye"

“You Only Live Twenty-Thrice” is a look back at the James Bond films.

Each Friday until the release of the 23rd official Bond film, “Skyfall,” we will revisit its 22 official predecessors from start to finish, with a bonus post for the unofficial films in which James Bond also appears.

Whither James Bond in the 1990s? A cultural relic crushed under the rubble of the dissolved USSR? The last bargaining chip for a beleaguered studio with a revolving door of leaders and owners? A name deplorably, and confusingly, hijacked to sell Cadbury candy?

Between 1989 and 1995, the real world that the Bond films came to reflect changed drastically. The Soviet Union’s dissolution was but one shift. The Berlin Wall fell. Germany reunited. The Persian Gulf and Bosnian wars began. Countries reduced nuclear arms left and right. Civil war in Rwanda claimed nearly a million lives.

After six years away, did the world need James Bond?

This question simultaneously haunts and invigorates 1995’s “GoldenEye.” And, in one of the franchise’s most adrenalized action sequences, the answer arrives in a moment of cerebral context and kicked ass.

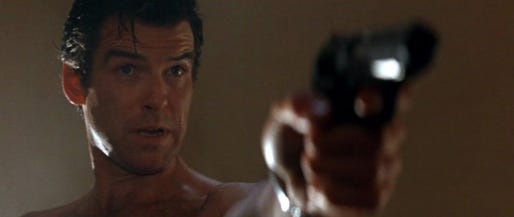

Bond (Pierce Brosnan, in his long-overdue debut in the role) has narrowly escaped death at the hands of Ouromov (Gottfried John), a rogue Russian general. After the ensuing firefight, Ouromov kidnaps Natalya Simonova (Izabella Scorupco), a hapless computer programmer and sole survivor of an Ouromov-orchestrated slaughter.

Bond could leave Natalya behind; after all, he’s now seen the face of Janus, the Russian gangster with a plan to commandeer a satellite weapon for dirty deeds. But that? That is not what heroes do.

Any lingering doubt of Bond’s place in the new world order is obliterated with the bricks through which he blasts that tank. It’s both a breathtaking effect and a brilliant assertion that this is a legendary face of heroism — a man undaunted by danger and unafraid to literally knock down a wall for what’s right. This scene occurs at the end of the film’s second act, but it’s the moment that Brosnan truly arrives at his own interpretation in the role as an almost balletic man of action — less visibly tortured than Timothy Dalton, more brutally efficient than Roger Moore.

And it’s not simply a sight gag when the Pegasus statue adorns Bond’s commandeered beast of war like a cement hood ornament. Here, Bond evokes Bellerophon, a Greek hero who tamed the Pegasus and rode it to victory against monsters most foul. An impulsive, brash hero facing and conquering the strange and unknown en route to triumph? What better metaphor for a post-Cold War Bond?

This isn’t the only mythological meme in “GoldenEye”; not by coincidence does the villain brand himself Janus, after a two-faced Roman god of beginnings and transitions who could look to the past and the future. This is a villain on whose mind yesteryear weighs heavily, painfully and unforgivably, and he will put 007 through his paces.

Sure, “GoldenEye” suffers from some ill-aged, mid-’90s effects work, but it remains an engrossing, emotionally engaging introduction to Brosnan’s Bond — parceling out a potent pocket of pain for the character en route to the reboot of 2006’s “Casino Royale.”

It certainly snatched a major victory from the jaws of what seemed like certain defeat. What remains the longest hiatus in franchise history jeopardized the series’ longstanding promise: “James Bond will return.”

The box-office fizzle of 1989’s “Licence to Kill” shook and stirred the Bond camp. John Glen, director of five consecutive films, was tossed. So, too, was Richard Maibaum, nearly synonymous with the series after co-writing 13 of its 16 films. Save “additional dialogue” for 1968’s “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang,” Maibaum wrote virtually nothing else in the last 30 years of his life, which ended after illness in 1991.

Producer Albert R. “Cubby” Broccoli put Danjaq, the parent company of EON Productions (which makes the Bond films) up for sale. And he got embroiled in what became a multi-year battle over international TV rights to the Bond films — asserted by French mega-studio Pathe after merging with Qintex, an Australian broadcasting company that had bought MGM/UA, the distributor of every Bond film.

Production dates on a new movie passed in 1990, 1991 and 1993. After that, a new regime at MGM/UA made amends with Broccoli and began talking Bond on the producer’s terms — which included honoring Dalton’s three-picture contract. But as production was delayed yet again in early 1994, Dalton, five years older after his last go-round and no start date in sight, announced he wouldn’t be returning.

This wasn’t a new problem, but finding a replacement was never easier. Post-“Remington Steele,” Brosnan’s career became a stalled-out mess of TV action, straight-to-video schlock and brief turns in “The Lawnmower Man,” “Mrs. Doubtfire” and “Love Affair.” Moreover, becoming Bond let Brosnan honor the wish of his late wife, Cassandra Harris, who introduced Brosnan and Broccoli while on the set of “For Your Eyes Only” and succumbed to ovarian cancer in 1991.

And with Broccoli’s declining health, two longtime Bond-film associates stepped into the producers’ spots — his daughter, Barbara Broccoli, and stepson, Michael G. Wilson, both actively involved in various franchise roles for years. Theirs was the first Bond film to not use any existing elements from Ian Fleming’s source material.

New world. New Bond. New blood. New ideas. So, how does “GoldenEye” radically reintroduce us to Commander Bond? With the worst-ever musical fanfare to darken the gun sight through which the hero saunters. This sleepy, skronky score of “chicka-chicka” percussion, chintzy, synthesized brass samples and more chanting than an Enigma record comes from Eric Serra — the composer of choice for French filmmaker Luc Besson.

Save the sparsely somber, downbeat piano during Bond’s eventual meeting with Janus, there’s irreparable dissonance between Serra’s notes and the movie’s tone. Most telling: Serra’s original accompaniment to the tank scene was replaced by a piece from composer John Altman. Here’s Serra’s original take, fraught with weird, modulated voices that recall the Art of Noise run amok.

At least Bond is introduced with greater force, pounding the pavement on a dam adjacent to a USSR chemical weapons facility. (As it turns out, we’re in 1986, with history rewritten to put Brosnan in the Bond role then, as was originally intended.) He accesses the facility only after a jump from atop the dam — a real-life 720-foot dive performed by Wayne Michaels that set a record for the highest bungee jump off a fixed structure. A 2002 Sky Movies poll called it the best movie stunt of all time. Clearly, those people have forgotten the opening moments of “The Spy Who Loved Me” or even “Moonraker,” in which prerequisite safety measures weren’t plainly visible the entire time.

But Bond isn’t the only MI6 agent there; Alec Trevelyan, 006 (Sean Bean), awaits him for a mission to destroy the facility. “For England, James?,” Alec asks before action. “For England, Alec,” goes the familiar, confident response of a longtime comrade. Once spotted, Alec is far more ruthless with his weapon, and an itchy trigger finger puts him at the wrong end of Ouromov’s gun. After a nearly point-blank bullet to Alec’s head, Bond flinches for his friend and commences his escape.

It’s not promising to see “GoldenEye” hinge the kicker of this 1995 sequence on the sort of visual effects that felt hoary in 1985. But still, someone actually jumped from that motorcycle midair; stuntman B.J. Worth has said he could feel the plane’s kerosene spray on his face.

“GoldenEye” is the first Bond film to use computer-generated effects. And where they truly come in handy are in Daniel Kleinman’s opening credits. Kleinman honors the time-honored traditions of Maurice Binder (who died in 1991) while introducing one himself: a sequence that befits the story to follow. In almost Dali-esque fashion, scantily clad hotties use their stilettos to topple figurehead statues and dismantle the hammer and sickle. But even in Tina Turner’s sufficient, if not terribly stirring, Bond theme (written by U2’s Bono and The Edge), there’s a sinking sensation that “GoldenEye” might just be going through the motions.

And despite the nice “Goldfinger” homage, that feeling continues during a muscle-versus-hustle car chase in Monte Carlo. It’s between Bond’s Aston Martin DB5 (later replaced by a BMW Z3 per a three-picture deal for product placement) and a Ferrari F355 driven by an as-yet-unknown femme fatale.

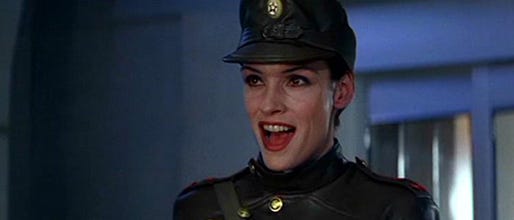

Ah, but the fear of middling stuff gets sloughed to the side once we see this leggy beauty in action. Xenia Onatopp is an amorous anaconda who lures men into bed and squeezes the life out of them with her seemingly iron thighs. Famke Janssen so lustily throws herself into these sexual kills that you can practically sense her precise moment of orgasm with the popping of bones. This is the first time we’ve seen a Bond girl so actively, remorselessly evil; only May Day from “A View to a Kill” comes close, but even she came around to 007’s way of thinking by the end. Onatopp cannot be persuaded; Bond will either be her executioner or her victim.

She fuses the franchise’s legacy of sex and violence into one unforgettable, eruptive, deadly package. And while Bond neither sleeps with nor succumbs to her — “Once again, the pleasure was all yours,” she snarls after he bests her once again — Janssen is a flesh-and-blood predator whose juices flow with the thrill of the hunt.

“GoldenEye” pleasantly tweaks old standbys as well. Moneypenny is no longer a mere formality, as Samantha Bond gives her the same effortless, flinty moxie as Lois Maxwell in her heyday. To her, the penalty for Bond’s “sexual harassment,” words finally spoken, are that he may one day have to make good on his innuendoes. And although there’s a tinge of sadness in seeing once razor-sharp Desmond Llewelyn clearly reading lines off cue cards, Q is a wilier old coot, finally sharing Bond’s middle-school chortle over the cachet of cool contraptions at his disposal.

The movie reserves its most radical re-envisioning for M, a formidable, newly female presence played by Judi Dench — who has continued to hold the role through six more movies. No longer the simple authority figure Bond either obeyed or defied, Dench’s casting creates an ideological battle of sorts for control of this particular coop — the mother hen versus the cock of the walk.

She’s not interested in how her predecessor minded the store, openly branding Bond a “sexist, misogynist dinosaur” and “a relic of the Cold War” over drinks in her office.

"You think I’m a bean counter,” she says to a snide, petulant Bond in her tirade. “But I have no compunction sending you to your death.”

Dench specializes in this stolid, impassive, no-bullshit berating, and there’s a cold, snapping sting to her final statement. Moments later, she softens the blow by telling Bond to “come back alive” from a mission to investigate Onatopp and Ouromov’s theft of an attack helicopter. But it doesn’t dilute the potency of their relationship.

M is the lone woman in a sandbox of men, and it’s handcuffing her influence. And besides, isn’t intelligence gathering supposed to be safer now? More distant and detached, with the action carried out by drone planes and missiles? But she knows Bond, with his old-school, on-the-ground dedication, is her best defense. Here begins a begrudging, often-squabbling mother-son bond that, from all indicators, comes home to roost in “Skyfall.”

Onatopp and Ouromov’s trail leads to a wintry bunker in Severnaya, where Onatopp guns down everyone with a smile before the duo absconds with controls for GoldenEye — a long-dormant Soviet satellite weapon capable of wiping out entire cities with an electromagnetic pulse or EMP. What they don’t know is that Natalya has survived; what she doesn’t know is that her presumed-dead, smarmy-horndog cubicle-mate Boris (Alan Cumming) is actually one of their stooges.

One of the movie’s central questions: How can you move on after you survive an attack your close colleagues don’t — ones who allegedly died in the service of a greater nationalistic ideal for the benefit of their country? If you’re wondering how that applies to 007, well, Sean Bean isn’t in this movie for nothing.

There are helpful Russian gangsters like Valentin Zukovsky (Robbie Coltrane), who, after quid pro quo from Bond, arranges a meeting with Janus. And then there’s Janus himself — the pseudonym of Alec, whose ragged, right-cheek scar represents a face gazing into the past.

When Bond discovers Alec is alive, it’s in a graveyard of titans who have fallen into disrepair and irrelevancy — the same traits Alec ascribes to MI6, against whose interests he was working from the get-go. That’s because his thousand-yard stare into bygone days goes back well before his work with Bond.

We learn why in an unforgettable scene of existential drama — rife with betrayal, questions of loyalty and how men of violence balance their karmic ledger — in which Bean delivers the meatiest, most sobering Bond-villain monologue of all. It’s one that solidifies our suspicion that for the 33 years we’ve known Bond, there are consequences we can’t even begin to comprehend.

Note how director Martin Campbell and cinematographer Phil Meheux frame Bond and Alec like chess pieces — moved around by an unseen, omniscient master and sacrificed as is seen fit. And the way the light hits them emphasizes the dark and grittiness of their surroundings — brief shafts and blasts that obscure faces and truth. It’s no wonder that Campbell would return to more explicitly explore Bond’s tumultuous inner turmoil 11 years later with “Casino Royale.”

“Come back alive,” M has told him, but to what kind of life? One in which love, friendship and certainty are so easily annihilated? “GoldenEye” treats 007’s motivation, his very livelihood, as a zero-sum game fraught with impossible choice between friends and missions. And although Brosnan fits silkily into Bond’s suaveness, he’s almost all business here, and like Dalton, we see hints of roiling anger. Even the woman with whom he enjoys a casual sex tussle at the beginning is an MI6 analyst gauging his psychological fitness. For all the confidence he carries into the role he was born to play, Brosnan is unnerved at all the right moments.

And Alec will doggedly pursue 007 far beyond this movie. That’s because he breaks the bottle into which Bond has stuffed any too-personal moments of carnage and casualties. Psychologically, he’s the greatest foe Bond has ever faced — a mirror-cracked reflection of his heroism. His petulance, inferiority complex and physical might all roll into one compelling characterization. And he’s the perfect foe against whom to pit Bond in a savage hand-to-hand brawl 500 feet above the ground.

Working on Alec’s behalf, Ouromov and Onatopp have given him the GoldenEye. With Boris’s help, Alec intends to clean out the Bank of England and use the satellite’s EMP to erase the evidence, destroy its records and ruin Britain’s economy. Bond and Natalya eventually track Alec and Boris to Cuba, where the two duke it out from a precarious position above a satellite dish. It’s a wholly believable pummeling between blood brothers whom betrayal has torn apart. Save a few fleeting moments, Brosnan and Bean performed these stunts themselves, and Brosnan’s hand injury even caused a delay in filming.

It’s a stone-cold moment of retribution when Bond drops Alec … undercut moments later by the warm smile he flashes to Natalya as she approaches in a helicopter. Yet again, the series isn’t ready to lay Bond’s psychological complexities completely naked, cold and bare. But in ending a long, six-year hiatus, “GoldenEye” can hardly be faulted for occasionally conceding to casual entertainment — especially with a superior villain, action sequence and Bond girl of all-time status.

Whither James Bond in 1997, 1999 and 2002? Leading the charge of blockbuster thrill machines, some of them bizarrely brilliant. Whither James Bond in 1995? Back, with far more authority and accomplishment than expected.

Next week: "Tomorrow Never Dies"

BULLET POINTS

“GoldenEye” means far more than just the title of a James Bond film and flagship Nintendo 64 title. Ian Fleming created 007 while writing at his Jamaican estate, which he nicknamed “Goldeneye.” Plus, Operation Golden Eye was the name of a World War II plan from the Allies to monitor Spain after the Spanish Civil War should it align itself with the Axis Powers. That plan’s architect? Lt. Commander Ian Fleming of British Naval Intelligence.

Mere months after her breakout role opposite Chris O’Donnell in “Circle of Friends,” Minnie Driver briefly turned up in “GoldenEye” — playing Russian gangster Valentin Zukovsky’s mistress and unglamorously warbling Tammy Wynette’s classic “Stand By Your Man.”

MGM approached John Woo to direct “GoldenEye,” and he declined. However, “GoldenEye” is still the first 007 film to be directed by someone other than a Brit, as Martin Campbell is a native New Zealander.

“GoldenEye” is the second straight 007 film to not shoot at Pinewood Studios, home of the famous 007 Studio. At the time, it was being used for “First Knight,” which co-starred the inaugural onscreen 007, Sean Connery. Instead, producers converted an abandoned Rolls-Royce factory and christened it Leavesden Film Studios.

To avoid destroying St. Petersburg’s streets during the tank chase, the Russian tank’s steel tracks were replaced with rubber tracks from a British tank. A trained stunt driver also sat prone and hidden in the tank, controlling it while it looked like Pierce Brosnan, hair billowing in the wind, was actually driving.