You Only Live Twenty-Thrice: "The Spy Who Loved Me"

“You Only Live Twenty-Thrice” is a look back at the James Bond films.

Each Friday until the release of the 23rd official Bond film, “Skyfall,” we will revisit its 22 official predecessors from start to finish, with a bonus post for the unofficial films in which James Bond also appears.

Mysteriously fluttering strings always swell and retreat in the “James Bond Theme.” But the extremes of those musical dynamics never quite felt as dramatic and different as they did in the opening fanfare of “The Spy Who Loved Me.”

Fresh off news of the death of prolific composer, songwriter and arranger Marvin Hamlisch, these ears might have been more finely tuned to specifics of crescendos and decrescendos in residence since 1962. But the idea of injecting noticeably improved nuances into a familiar, rumbling rhythm almost doubles as “Spy’s” thesis.

No more bizarre, if reasonably entertaining, diversions into blaxploitation and martial arts cinema. No more tin-whistle trivializations of some of the era’s finest stunt work. And, thank heavens, no more Sheriff J.W. Pepper. “Spy’s” global grandeur finally gave Roger Moore a truly worthwhile adventure — one as breathtakingly assured in acting and action that it’s no wonder “Spy” is his favorite.

It kicks off with one of cinema’s most jaw-dropping stunts of all time, provides the shrewdest, most sophisticated characterization of a Bond love interest yet, climaxes in a ginormous Bond set by imaginative production designer Ken Adam, and introduces 007’s most physically frightening opponent ever. With the franchise in a state of flux, such hugeness was essential.

Although 1973’s “Live and Let Die” was a hit, the box-office take for 1974’s “The Man with the Golden Gun” tumbled 40 percent. The following year, producer Harry Saltzman, a Bond backer from the get-go, sold his entire stake in EON Productions company to stave off financial catastrophe from unrelated ventures.

In the first of several Bond ventures as sole producer, Albert R. “Cubby” Broccoli showed interest in Steven Spielberg to direct, but after waiting to see “how the fish picture turns out,” Spielberg was no longer a for-hire filmmaker. Guy Hamilton, Bond’s current go-to guy, bailed when approached to direct “Superman: The Movie” — a job that instead went to Richard Donner. Eventually, Lewis Gilbert, who directed “You Only Live Twice,” returned to the director’s chair.

Originally, “Spy” was to center around uber-villain Ernst Stavro Blofeld’s deposition as leader of criminal organization SPECTRE at the hands of international terrorists. But then Kevin McClory — the man with film rights to “Thunderball” — filed an injunction that prevented EON from using either Blofeld or SPECTRE and prompted a major rewrite.

Why didn’t McClory do the same for “Twice,” “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service” or “Diamonds Are Forever”? The answer is simple: He wasn’t actively developing his own “unofficial” James Bond movie when those went into production.

From a creative standpoint, a ban on the bald baddie was a blessing in disguise. After five movies, Bond and Blofeld’s battles were beyond played out. Plus, it forced Bond’s screenwriters to look more closely toward real-world politics for their plots. The cynically suspicious posturing and one-upsmanship that defined the Cold War’s second phase — which ramped up right around the time of “Spy’s” pre-production — offered a timely boost for “Spy” and every Bond film for the next decade.

“Spy” didn’t hit theaters until 1977, a three-year hiatus that was then the series’ longest. But the improved production values are evident from the start, in which Soviet and British nuclear submarines mysteriously disappear from the ocean. (“Spy” sort of reheats “Thunderball” and “Twice,” but it’s all in this dish’s spices.)

Bond is reassigned from his mission in the Austrian Alps, but he must first escape a cabal of skiing gunmen. So begins one of 007’s craziest opening gambits, which culminates in an absurdly dangerous stunt that carries the tangible, nerve-rattling authenticity of a human in jeopardy. At a cost of $500,000, it’s the sort of mind-blowing stunner you rarely see anymore amid digital effects and liability concerns. And Hamlisch, who drops the score out altogether, shows it proper reverence.

In the early 1970s, Rick Sylvester skied off the top of El Capitan in California’s Yosemite National Park — descending approximately 3,000 feet by parachute. The Bond team took note and paid Sylvester $30,000 to double for Bond and ski off the top of Canada’s Mount Asgard (which stood in for the Alps).

The camera angle on this jump is phenomenal for multiple reasons. It dizzyingly sells the height from which Sylvester is plummeting. There’s no doubt whatsoever that it’s a real person unlike, say, “The Fugitive.” And depth-perception trickery makes it look like Bond’s body will, at any moment, shatter on hard-packed snow.

What a triumphant transition into a song with lyrics asserting “Nobody does it half as good as you.” Although musically rooted in that era’s mellow adult contemporary sound, the boyish boastfulness of Hamlisch’s lyrics, Carly Simon’s impeccable vocals and its gradually building flourishes establish “Nobody Does it Better” as a legendary Bond theme.

“Spy” then leaps headlong into its plot and never once flags. The vanished submarines targeted by a submarine tracking system that’s making the rounds on Egypt’s black market. Bond is dispatched to Cairo to trace its source, which he learns is Karl Stromberg (Curt Jurgens), “one of the premier capital exploiters of the West.” A reclusive shipping tycoon and scientist, Stromberg has trapped the submarines, crew and all, in the belly of the Liparus, his gargantuan supertanker.

Adam did not merely want to replicate Blofeld’s beautiful underground lair from “Twice,” but no soundstage was sizable enough to house the supertanker. The solution? Build a new Pinewood Studios soundstage in London, nicknamed the “007 Studio,” for $1.8 million, and with a 1.2 million-gallon water tank.

Water is everything in “Spy.” It’s at the ocean’s blackest depths that Stromberg hatches his plot from Atlantis — an underwater base with windows onto marine life that occasionally and ominously ascends.

“For me, this is the world,” Stromberg says of Atlantis. “There is beauty. There is ugliness. And there is death.” It’s an eloquent, chilling elucidation of his reason for his scheme — using the subs to spark an annihilative Armageddon and then creating a new, beautiful world under the ocean unsullied by man.

A sixtysomething sociopath who sometimes resembles an even nastier Don Rickles, Stromberg is not physically imposing. But, like Auric Goldfinger before him, he is ruthless, methodical and patient when it comes to murderous plans.

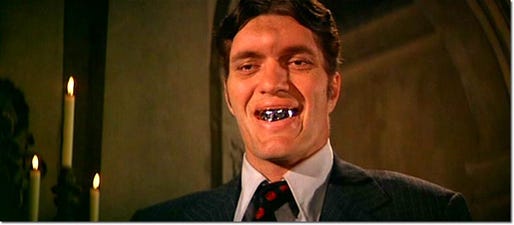

Besides, Stromberg need not lift a finger with a henchman like Jaws (Richard Kiel). This 7-foot-tall monster could pop his targets’ heads like grapes but instead prefers to drain their blood by biting them with his dreadfully disfigured metal teeth. Everyone tends to freezes up around Jaws, whose graceless lumbering seems a hindrance to catching someone who would only just run away. But he’s so imposing and horrendous, it’s as if his prey is stricken dumb by the very sight of him.

And the wild, up-close ferocity with which Jaws strikes brands him a true predator. Hell, he’s able to kill even a shark with his mouth, and that there’s easily accessible photo of this scene is one of the Internet’s great shames. (And don’t think for a second that Jaws eating a shark isn’t a playful jab at Spielberg.)

Jaws is an ubiquitous, seemingly unstoppable foe for Bond, and the film gives him one towering sequence after another. As he stalks 007 amid ancient pillars, you get the feeling he could topple one of them with one swing. And note, during this train fight, that Kiel’s fist appears to be roughly the size of Moore’s head.

However, for all of Jaws’s horrifying accoutrements, “Spy” realizes this barbarian’s potential for physical comedy — namely as he peels apart a van panel by panel.

Immobilized only by principles of electric conductivity and magnetism, Jaws remains the only lackey to return in a Bond film (as he would in “Moonraker”).

He also walks away with hardly a rumple in his suit from the film’s centerpiece car chase — which takes a most unexpected off-road detour. Watch Bond’s Lotus tightly slide between two tractor-trailers, see it soar parallel to a helicopter before diving toward what seems like certain death, and enjoy more masterful tactile thrills.

So much greatness and still no mention of Soviet spy Anya Amasova, aka Agent XXX — Bond’s first love interest to be fully rounded in ways that go beyond titillation (even if she does bare her breasts in shower-scene profile). The term “Bond girl” seems trivial, for Anya is as far from a naïve, easy ditz as can be. It’s a credit to the performance from Barbara Bach — cast just days before shooting but able to conjure up the most fascinating romantic chemistry Moore would ever share.

That’s because when Anya does make a romantic overture, Bond takes a risk by taking it at face value; even resting her head on his shoulder feels like competition, not capitulation. Deservedly boasting the most screen time of any love interest, XXX is at 007’s side for nearly the duration of the film — which builds steady suspense by masking her true intentions.

Bond and Anya form a hesitant partnership, brokered by the KGB and MI6 in the spirit of détente and for the sake of finding their subs and saving the world from Stromberg. Anya has little reason to trust MI6 agents, especially the one who killed her lover in the Austrian Alps days earlier. We know it’s Bond, but neither of them does yet, and just as their mutual mistrust melts, the truth comes out in the open.

The scene in which they confront this cold, hard fact — and Anya swears vengeance once the mission ends — doesn’t directly tie back to “Die” or “Gun.” But Moore’s hardened response comes from a man who knows the spy game is no trifle. Despite their small-scale personal-revenge plots, Kananga and Scaramanga pounded into Bond the resolve to use violence when necessary.

He certainly must use it to escape the Liparus — where he’s eventually taken captive along with the submarine crews — along with resourcefulness and not a little bit of pure luck. With the most impressively staged climactic action since “Service,” the big finish includes a thrilling breakout, Bond’s tense removal of a nuclear missile’s detonator, and a sneaky siege on the Liparus’s control room.

And unlike Britt Ekland’s dim-bulb agent in “Gun,” you cheer for Bond to rescue Anya after Stromberg absconds with her to Atlantis. Yes, Bond has bedded Anya, but he also comes to respect her as an equal who has, time and again, saved his bacon. And as for “violent,” how else would you describe Stromberg’s painful demise?

In a call-out to Hamlisch’s musical “A Chorus Line,” the movie closes with a Broadway-sounding spin on “Better.” Cheesy? Sure. But the mental image of a tops-and-tails kick line is perfect for a film that shows Bond can still give ’em the old razzle-dazzle.

Here, “Nobody Does it Better” isn’t simply a theme song, it’s a forceful, but fun, statement of purpose. And “Spy” proved to be the definitive jolt the franchise sorely needed.

Next week: "Moonraker"

BULLET POINTS

"The Spy Who Loved Me" shares more than just a director and evil-plot narrative with "You Only Live Twice." James Bond's car/submarine was nicknamed "Wet Nellie" — a descendant of "Little Nellie," 007's gyrocopter from "Twice" who, as you may recall, "defended her honor with great success" against "improper advances."

Oddly enough, Jaws wasn't the first murderous henchman with steel teeth played by Richard Kiel. A year earlier, Kiel tormented Gene Wilder atop a train as the maliciously metal-mouthed Reace in "Silver Streak." It's been said that for "Spy," Kiel could only wear the prosthetic chompers for a few minutes at a time because of the pain they caused.

"Spy's" script was credited to longtime Bond scribe Richard Maibaum and newcomer Christopher Wood, but it synthesized the contributions of several uncredited screenwriters. Among them: John Landis, who had not yet even made "Kentucky Fried Movie" and had been a European-film journeyman as an actor, production assistant and even stuntman; Stirling Silliphant, an Academy Award-winning screenwriter for "In the Heat of the Night"; and Anthony Burgess, author of a "A Clockwork Orange," who allegedly birthed the idea for Stromberg's submarine silo as seen in the final film.

Burgess wasn't "Spy's" only odd connection to "A Clockwork Orange." Cinematographer Claude Renoir had more than 80 films under his belt when he became "Spy's" director of photography And yet he was nervous about how to properly light scenes in Stromberg’s gigantic supertanker (built in the newly christened 007 Studio at Pinewood Studios). So, production Ken Adam called in an old pal and collaborator … Stanley Kubrick. On a Sunday morning, Kubrick and Adam surveyed the set themselves, with Kubrick determining all the right lighting cues. Hear more of the story in Adam’s own words:

Although nothing like the tragic incidents that befell “Twice,” this film had some injurious moments as well. While filming his standoff with Stromberg, Roger Moore was injured when his posterior catches light from a premature explosion of explosives on his chair.