Churchill

“Churchill” shows the great man not at his zenith, but at his lowest. Having led Great Britain valiantly through the darkest days of World War II, his nation almost singlehandedly defying Hitler for more than two years, the Prime Minister shown here is aged, worn down, dyspeptic.

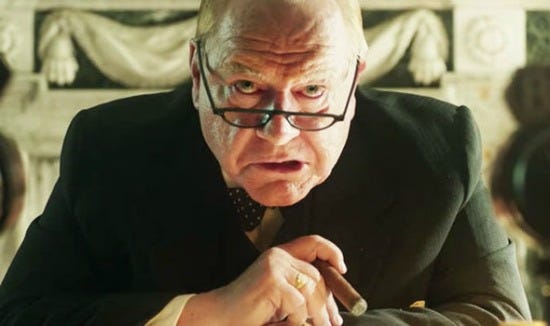

As played by Brian Cox, Winston Churchill is resentful of other Allied leaders who have arrived to supplant him, especially Dwight Eisenhower (John Slattery). In the days leading up to Operation Overlord — or D-Day, as it would come to be known after — Churchill is the thorn in everyone’s side, insisting the plan is ill-thought and will lead to slaughter.

He draws up alternative plans for Overlord, undermines the operation through his connection with the King and even prays to God for poor weather to cancel the expedition. The movie, directed by Jonathan Teplitzky from a screenplay by Alex von Tunzelmann, implies that Churchill does so not out of an abundance of caution but because he is haunted by his own wartime experiences sending young men to their deaths in Turkey during the Great War.

Much like a certain politician of more contemporaneous vintage, this Churchill is incapable of not making everything about him.

Cox doesn’t particularly resemble or sound like Churchill, but manages to suggest the soul of a man who can inspire others even as he is paralyzed with fear and loathing. Jowly (with prosthetics), borderline decrepit and eternally smoking his totem-like cigar, Cox strappingly evokes the iconic image of Churchill.

It’s definitely a postmodern depiction of a historical figure, as focused on showing his weaknesses as his magnitude.

It’s also, from what I’ve gathered, a rather ahistorical musing on the man. While it’s true Churchill opposed an Allied invasion of German-held Europe when it was first proposed in 1942, by the time June 1944 rolled around, he was fully supportive of Eisenhower’s plan. A number of historians have attacked the film for its inaccuracies.

I suppose if you took “Churchill” as the un-ornamented recital of historical events, you might find its depictions more egregious. But this is historical fiction, much in the mold of “The King’s Speech,” which was set in roughly the same time and place. It is the very definition of something meant to be taken seriously but not literally.

The movie closes with a text scrawl in which Churchill is described by many as “the greatest Briton ever,” so its intent seems clear to me — piercing the myth of the man, rather than exalting him.

Miranda Richardson plays Clementine Churchill, his long-suffering wife who at times seems barely able to stand the man she married. Her unofficial position is to smooth the rends Winston makes in his dealings with others. Their own fractious relationship is always relegated to the back burner. When he screams at his new, young secretary (Ella Purnell) for typing his dictation single-spaced instead of double, it’s Clem who defuses the situation, taking the PM aside for a scolding — because she’s the only person permitted to do so.

James Purefoy plays King George, who is easily swayed by Churchill’s words — at least initially — having depended on him for so long. He gets a nice speech about upholding one’s duty even if it runs counter to your own instincts. Richard Durden plays Jan Smuts, the prime minister of South Africa and Winston’s old comrade, who acts as a sounding board and runs interference with other bigwigs. Julian Wadham is Bernard Montgomery, Britain’s greatest (and prickliest) general, who struggles to hide his contempt for a man he regards as belonging to the past.

Think of “Churchill” as a sister film to “Steve Jobs,” starring Michael Fassbender as another titanic figure who evokes conflicting opinions. These are historical ruminations, not recitations. The Churchill played by Cox may well bear little resemblance to the actual man. But it’s a fascinating portrait nonetheless.