Ennio

Even if you don't know Ennio Morricone, you know his legendary film music. Guiseppe Tornatore's new documentary gives us a chance to get to know the man.

Outside a movie theater, few people even think about film music, let alone listen to most of it. Once in a while, though, a sound from the world of film infects the collective unconscious so completely that people who have never heard of the composer, or sometimes even the film itself, know it almost instinctively.

Sharks are now indelibly linked with John Williams’ two-note ostinato from “Jaws.” Shrieking strings mean murder because of Bernard Herrmann’s “Psycho.” And a warbling, high-pitched whistle accompanied by a twanging electric guitar now - rather improbably, when you think about it — says “Western,” thanks to one Italian genius.

Ennio Morricone.

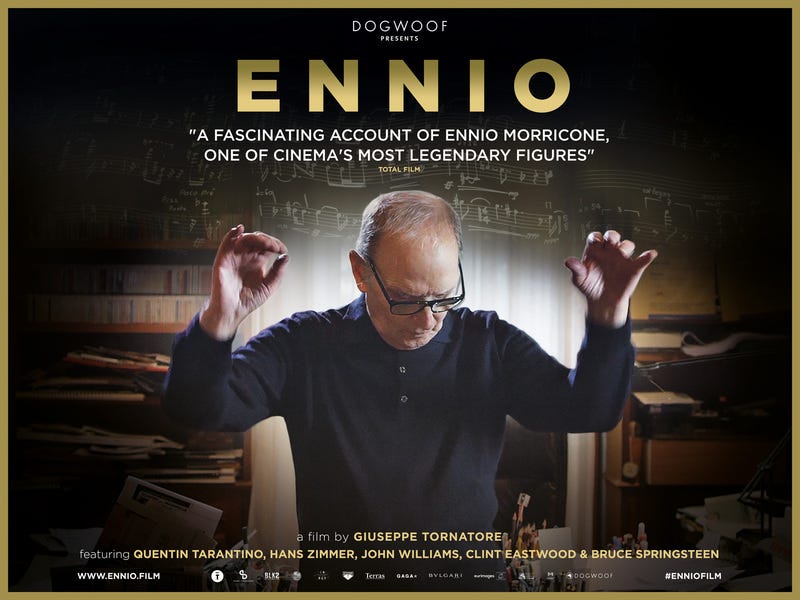

In a sprawling 2½-hour film documentary, simply called “Ennio,” the director Giuseppe Tornatore gives us a comprehensive and heartfelt portrait of the maestro who revolutionized the art of film scoring again and again over a career that spanned seven decades and more than 400 films. With interviews completed before Morricone’s death in 2020, “Ennio” was first screened in 2021, has been seen since on the festival circuits and other limited engagements, and is available June 25 for the first time on DVD and streaming from Music Box Films.

It is hardly an exaggeration to say that Ennio Morricone’s music has influenced nearly every composer of movie music who came after him. If there were a Mount Rushmore of film composers, the bespectacled face of Ennio would certainly be there. Yet even with all this, as “Ennio” reveals, Ennio Morricone himself never felt he had done enough, and struggled for recognition and approval all his life from those who, for one reason or another, withheld it from him: His tough working-class father. An imperious and elitist mentor from the academic establishment of classical music. Even the Academy Awards.

In “Ennio,” Tornatore takes a fairly even-handed approach to his subject. Considering how deeply intimate many of his films are, it is surprising that Tornatore chooses this path, rather than something more personal about his relationship with his friend and frequent collaborator. (Morricone wrote 13 scores for Tornatore’s films over the years, but even my personal favorite, the achingly beautiful “Cinema Paradiso,” gets only a brief highlight.)

Instead, Tornatore presents himself as just one among scores of Morricone’s friends and colleagues interviewed for the film, a constellation of the most influential filmmakers and musicians of the last seven decades, and even a few noteworthy Morricone enthusiasts like Bruce Springsteen and James Hetfield of Metallica. Combined with interviews with the composer himself, the result is a multifaceted view of a prodigy who seems to have been able to do anything musically - and did.

All these facets end up being the film’s greatest strength, as they are necessary to approximate a complete picture of the reserved Morricone, who is usually not forthcoming about who he is and how he feels.

A few telling anecdotes and vulnerable moments do give us glimpses behind those thick glasses into Morricone’s inner life. In one poignant confession, he explains that he avoided writing trumpet parts in some of his earlier work so he could avoid his mother’s repeated urgings to hire his father to play — he was a professional trumpeter who got Ennio into the family business of music, but by the time Morricone was writing professionally, he had to admit that Dad just wasn’t as good as he once had been.

But mostly, Ennio prefers to express himself through, and by talking about, his music. In a sense, he is the music.

Anyone who has heard Morricone’s scores, which fuse seemingly incompatible elements from coyote howls to pipe organs, will find a spark of recognition, then, in the variety and scope of his prolific career, and his constant struggle to reconcile disparate influences. “Always being himself, always being someone else,” says one interviewee, possibly the most succinct and insightful description offered in the film.

Also, if it weren’t for the rich array of interviewees describing all the different parts of Morricone’s career, it may simply be too hard to believe that one man could possibly have done it all. He was steeped in music almost since birth – in an ironic reversal from many artists’ biographies, Ennio claims that he dreamed of being a doctor, but his father insisted on placing him in a conservatory at the age of 12, by which time he had already taught his son how to read music and play several instruments. Here, he came under the wing, and shadow, of his teacher Goffredo Petrassi, a guardian of the Italian academic classical music tradition who was nearly impossible to please.

Meanwhile, he was constantly working – playing with and eventually replacing his father in professional trumpet gigs, and his work ethic quickly won him work as an orchestrator and arranger for television and pop songs, which were his gateway into the film business. As one of RCA’s chief arrangers in the 1950s and ‘60s, Morricone was a constant innovator, toying with odd sounds like metal cans, infusing banal pop melodies with sophisticated counterpoint, or conjuring rhythmic innovations that kept the sound from falling into predictable patterns. He even formed an experimental musique concrète group on the side, finding new ways to play old instruments, or things that weren’t instruments at all.

Predictable patterns are perhaps what Morricone most hated – he didn’t like to repeat himself musically, but was asked to replicate his signature sound for dozens of Westerns after he hit the big time with his scores for his former schoolmate Sergio Leone’s iconic “Dollars trilogy” films with Clint Eastwood, including “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.” (He said of his later score for “The Hateful Eight” that it was his chance to “avenge himself on the Western.”) He also fiercely defended the correctness of his artistic instincts, refusing to let directors and editors fall back on temp tracks by other musicians, or force him into a style that he didn’t feel was right for a scene.

Nevertheless, he constantly labored under an “inferiority complex,” yearning throughout his career for the grudging respect of his mentor Petrassi and classical academia, which would not come for decades. A series of near misses also seems to haunt Morricone, like a lost opportunity to work with Stanley Kubrick on “A Clockwork Orange,” or the inexplicable fact that he failed to win an Oscar outright until 2016 for the aforementioned “Hateful Eight.”

Much of the second half of the film is a kind of travelogue of Morricone’s staggering filmography, in which there are so many highlights that several famous scores don’t even make the cut. (This may partially explain why the run time is as long as it is – how do you decide what to leave out of a career like his?) Along the way we discover both countless innovations from his impatient, experimental mind, and common threads that explain his music’s compelling appeal.

Time and again, his music creates “a tension whose resolution is ecstatic,” as one observer notes, a feeling both visceral and transcendental. In “The Mission,” a single oboe played in a forest becomes an explosion of spiritual exultation, and it is not too much of a stretch to hear this at work in the tense showdowns of Leone’s Westerns as well, raising an endless sequence of long shots and extreme close-ups into frenzied operatic grandeur before the first trigger is pulled.

After all this exhaustive investigation of a composer’s struggle with all the contradictions of his career, “Ennio” finally seems to find the composer allowing himself to acknowledge and enjoy his success in every musical field he has explored. He has ultimately quieted, or at least made peace with, the demons of doubt that haunted him. This makes for a satisfying conclusion, especially since Morricone himself could not have known that the film would end up being a eulogy of sorts. “Ennio” was released posthumously to a world of film lovers who will always be grateful to him for his tectonic influence on the art — and to the world well beyond. We will never again live in a world without Ennio’s influence, and we’re all lucky to have that.