Heartland: Attachment Project

Part documentary, part catharsis, Joy Dietrich's look at her own troubles bonding with her adoptive parents and those of other foreign-born children makes for a heady, emotional journey.

For Heartland Film Festival schedule and tickets, please click here.

Every parent remembers the first time their baby smiled at them. No doubt it caused deep feelings to well up inside them — ones of love and bonding. Surely, we also assumed, it was the same for the child.

But how can an infant truly understand and feel love, since its brain is barely developed enough to interpret the sights and sounds it experiences, let alone feel something as powerful as love? Scientists have developed entire reams of theories about the process by which baby and parent bond, which is generally organized under the title of attachment theory.

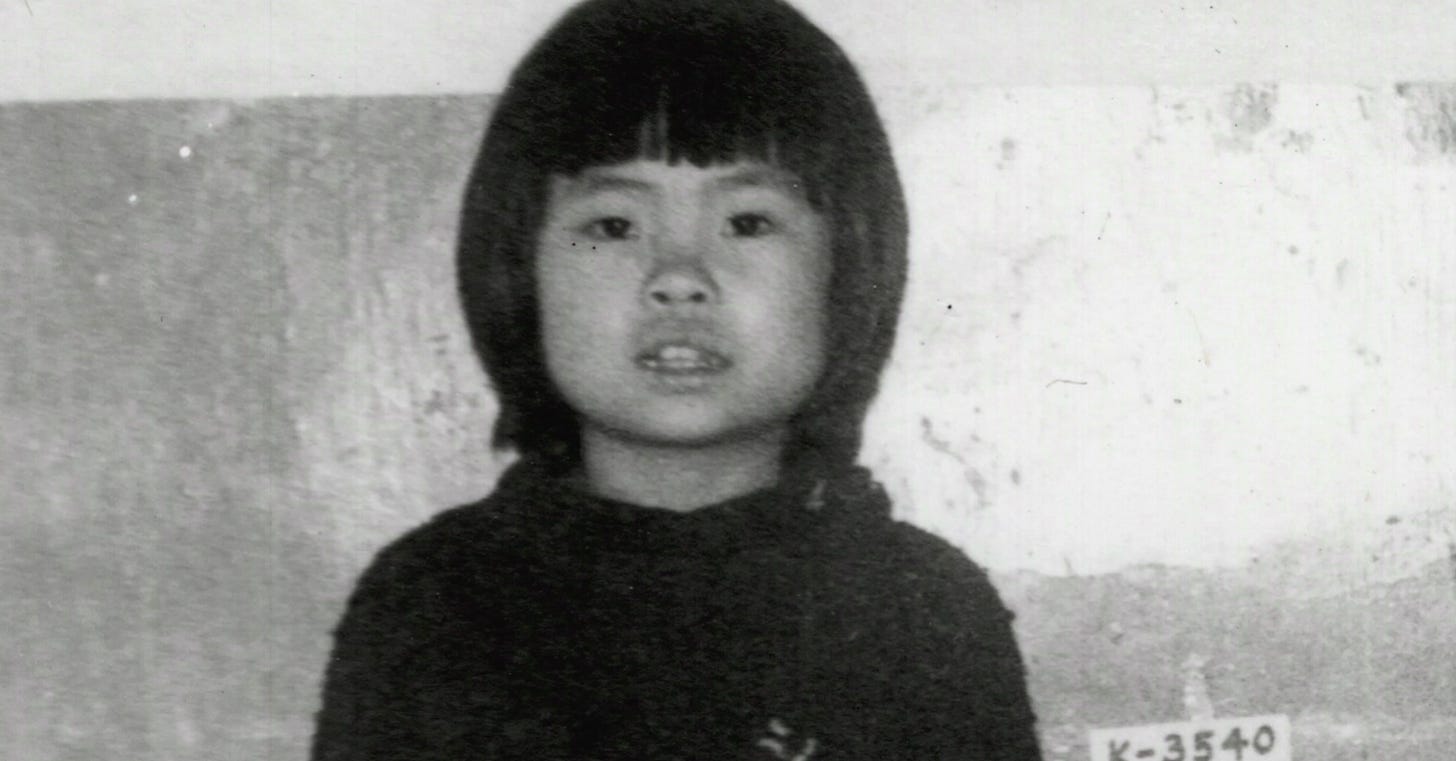

For journalist and filmmaker Joy Dietrich, attachment is something she’s been chasing all her life. Adopted from South Korea as a young child after being abandoned on the streets, she came to live with a Texas family that later moved to rural Indiana. The only Asian in the community, she already felt deeply estranged and that carried over to her adoptive parents, especially her mom, Linda.

At age 18 while living as an exchange student in Germany, she received a letter from her parents essentially cutting ties with her, explaining they would not pay for her college fees and wishing her the best in her “endeavors.”

Twenty-four years later, now in her early 40s and an accomplished filmmaker and reporter/researcher for the New York Times, Joy — who also has trouble maintaining romantic relationships — wants to explore this idea of attachment further. It means taking some painful steps into her own past and, eventually, confronting the mother and father who abandoned her for the second time in her life.

Dietrich does not undertake this journey alone. The film — part documentary, part personal catharsis — also follows two other people adopted from foreign countries who suffered attachment problems with their American parents. Amazingly, these encounters span a number of years, as we watch them grow from angry or sullen youngsters into more self-aware adults.

Like Dietrich, they remain in therapy struggling with what’s known as attachment reactive disorder.

Daniel was adopted from Romania at age 7. He recalls distinct memories of living in a huge room where dozens of children were confined to crib-like pens with little to do other than stare out the window. Meal times were a virtual frenzy as they fought and bit over scraps of food.

He was obviously pleased to arrive in Cleveland, Ohio and not have to worry about being fed and clothed, and free from the fear of constant physical abuse. But like Joy, he had trouble bonding with his parents and siblings, even though his environment was apparently much more loving than Joy’s. Things culminated with an incident at age 10 where he held a knife to his mother’s throat.

Most of the interviews with Daniel take place in his early to mid 20s, as he talks openly about his challenges in making and maintaining relationships. A coda near the end of the film offers a more optimistic glimmer for him.

Tara, age 16 when we first meet her in Columbus, Ohio, was adopted from China at a similarly young age. She seems more well-adjusted and “normal” than the other two subjects, though we soon learn this is because her disorder expresses itself through drawing inward and becoming depressed, rather than lashing out. She has a young sister, also adopted from China, who is outgoing and seemingly unaffected.

We follow Tara into her mid-20s, and learn that the loss of her adoptive father, Gary, who married into the family a few years after she emigrated, has been very hard on her — even though he was the figure she had the most trouble bonding with as a kid.

The documentary also gives us a glimpse into the various theories and treatments for attachment reactive disorder, which have changed quite a bit since Joy was a youngster but range widely in practice. In one, known as holding theory, the parent or even the therapist forcibly holds down the child or forces them to sit on their lap. Some of it seems to bear little distinction from outright abuse.

The film reaches its critical point when Joy decides to visit with her parents, who have since divorced, for the first time in more than two decades. Her dad is friendly but dismissive, wanting only to talk about his fishing boat. The real encounter is with her mom, Linda, now remarried and living in Louisiana.

It’s a torturous dialogue masked in a veneer of politeness, as the women exchange barbed accusations about their defunct relationship. Linda seems to regard being an adoptive parenthood as a very transactional endeavor, and she feels like she didn’t get enough back emotionally from Joy compared to what she put in, in terms of toil and especially financially.

This sequence occurs near the end of “Attachment Project,” and I’m glad it did — because we’re so emotionally wrung out after, it’s hard to keep focus.

If you think Joy Dietrich is just wanting to lay blame from her troubles at her mom’s feet, the existence of this movie is evidence itself of her desire to do more than just vent. No one seems to know why some adopted children, from the U.S. or abroad, quickly bond to their new parents while others never truly do. But Joy is trying her best to understand, by applying a journalistic lens to her own story and that of others.

This can be a tough movie to watch at times, and that’s why I so urgently recommend it.